What images come to mind when you think of a field ecologist? Do you see what I see? I see someone, probably in khaki shorts and a broad-brimmed hat, walking through thick rainforest, listening to the calls of birds, waving off insects determined to find a patch of skin to bite, and smelling the exotic aromas of plants and animals living, dying and decaying.

You may well be thinking that this is an idealised image of a field ecologist and while it may have been true 50 years ago, it’s harder to imagine now. After all, every day we hear about habitat destruction and how mankind is damaging the natural environment. But I’d like to propose that even 50 years, or 100 years, or even 1000 years ago mankind was having an impact on the environment and this idea of the ‘natural’ world really needs rethinking.

Take, as an Irish example, the Burren. I visited this area for the first time a few weeks ago and was stunned by the rugged beauty of the place. It was sparsely populated, only a few sheep and cows (and the occasional donkey) provided evidence of any human presence in places; how much more ‘natural’ could one get? Plenty more, it turns out, as the entire landscape is the result of human impacts.

The entire area is littered with signs of prehistoric people, the most striking of which was the 5,000 year old Poulnabrone portal tomb. This tomb dominates a limestone pavement with a view that stretches for miles across to the sea. Yet reading the information boards it quickly became apparent that this was not the landscape in which the tomb was constructed. At that time the area was heavily forested with small clearings made by people to farm and build their homes. The tomb would most probably have been largely hidden from all but those who knew its location. Yet over the next few thousand years people cut down more and more trees to make use of the timber and to clear the way for more farmland. However, the trees were the only thing holding the thin soil in place and with the loss of the trees, the soil soon followed, until all that was left were patches of vegetation and entire hillsides of exposed limestone bedrock. That stunning ‘natural’ landscape is the result of ancient habitat destruction!

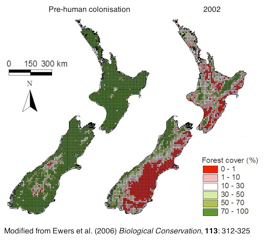

A similar story can be told across much of the world. New Zealand, adopted home of the hobbits, with its fields and rolling hills, was once almost entirely forest. Yet when the Maori reached the islands around a thousand years ago they proceeded to reduce the forest cover by almost half, and the European settlers reduced it by half again. In addition, the loss of so many endemic species also led to changes in the structure of the remaining forests, though precisely how is still being debated.

It’s the same the word over. Take, as a final example, Australia. The sixth largest country, the world’s largest island, yet it has only 0.33% of the world’s population. Surely humans can’t have had much of an impact there? Well, yes they can, particularly if you think that they are at least partly responsible for the loss of the megafauna. For more details on that I highly recommend Tim Flannery’s 1994 book ‘The Future Eaters’, with the teaser that I never knew that dung was so important to a properly functioning ecosystem! But even ignoring that, Aborigines had a long and close association with the land, heavily modifying environments through activities including the use of controlled burning.

I could go on (and on, and on) for every habitat on almost every continent, but it would get rather monotonous. My point is that when we look at the ‘natural’ word we rarely see something that’s never been touched by man however far into the ‘wilds’ we go. The ‘natural’ world has been modified, sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically, for thousands of years as countless generations have struggled to survive and prosper. Ecology, however much we like to think otherwise, always involves a human component. Sometimes the humans who made the impacts have long gone and the landscapes have become so normal and ‘natural’ its hard to think there was a time they were ever different. But if we are to understand the world we need to understand the historic impacts we have had, not just on climate, not just in towns and cities, but also on the ‘natural’ world.

Author

Sarah Hearne: hearnes[at]tcd.ie

@SarahVHearne

Image sources

Sarah Hearne

Ewers et al. (2006) Biological Conservation 113:312-325