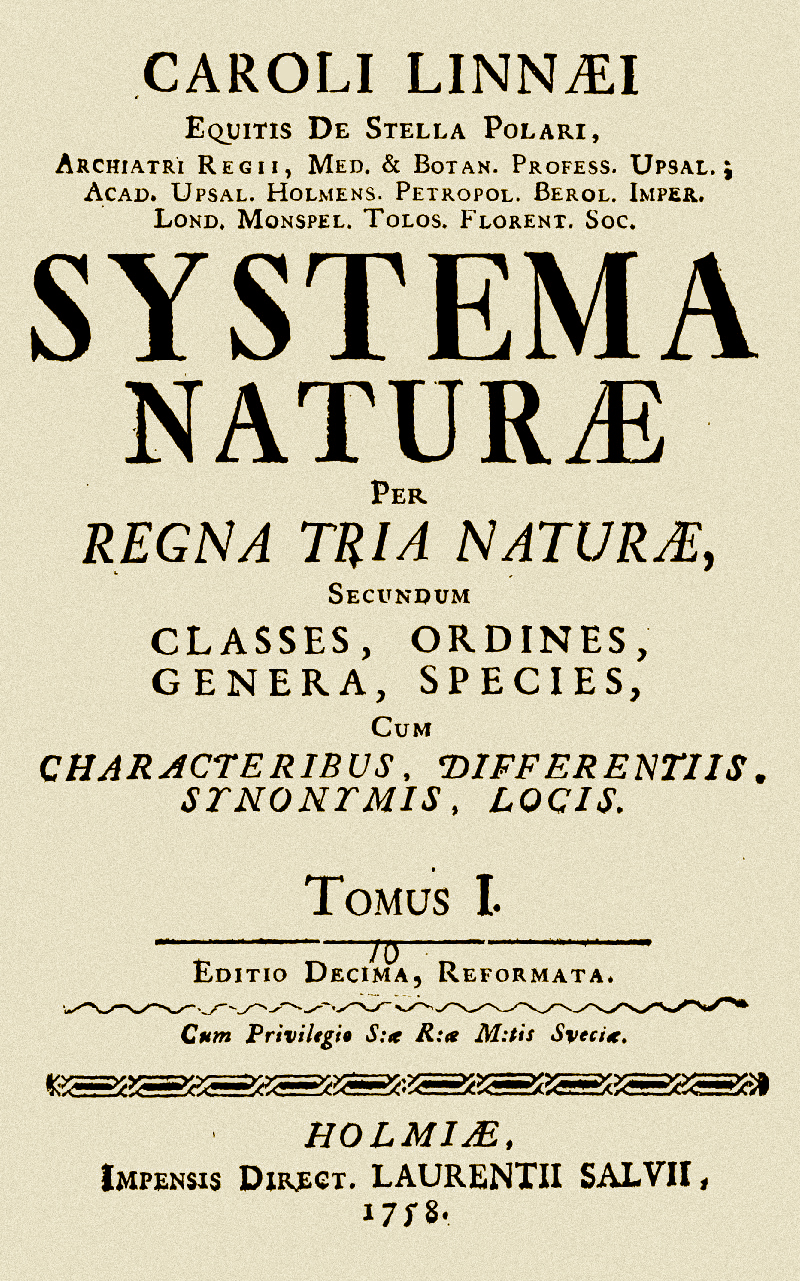

Carl Linnaeus has a lot to answer for. As a young medical student he became obsessed with botany, then a necessity as most medicines were derived from plants. At the time the naming of plants was a rather haphazard affair, some names were given to multiple plants, others could be many words long. It all made for great confusion and difficulty disseminating information. In an attempt to manage the situation, in 1735 he published the first edition of his masterpiece of classification, the Systema Naturae. Most people remember this book as being the first time that plants were classified according to the now familiar Kingdom, Class, Order, Genus and Species (family was a later addition). What they sometimes forget is that it was also the first time that plants, and later animals, were given a standardised binomial designation. This was a revolutionary idea and quickly came to dominate the literature and is still in place almost 300 years later.

Once a formalised system of naming organisms was in place the number of scientifically named and described organisms skyrocketed. The 1700s were a time of exploration, with ships sailing to the far reaches of the globe and returning with plants and animals never seen by Europeans before. It was a time of great excitement and scientific discovery. What could be simpler – find a new species, name it, describe it, move on to the next one. And so botany and zoology continued in this vein for a hundred years or so. But then came along someone else who also has a lot to answer for: Charles Darwin. His theory of evolution by natural selection introduced a little bump on the road to naming every species.

The problem can be traced far back into antiquity. Before Darwin, species were thought to be immutable, unchangeable, static. Ancient Greeks such as Plato believed that each type of animal had a ‘perfect’ form and the living animals were merely imperfect reflections of this ideal. Similarly, the Noah’s Ark story in the Bible mentions “kinds” (Genesis 6:20):

“Two of every kind of bird, of every kind of animal and of every kind of creature that moves along the ground will come to you to be kept alive”

These are versions of what is now called the “typological species concept”. It’s what most lay people use to distinguish between species. They might not know much biology, but they can tell you that a blackbird is a different species to a sparrow, or than an oak tree is not the same as a spruce tree. The problem with this concept is that under it a great dane would be considered a different species to a Chihuahua despite them actually both being a sub-species of the grey wolf.

Clearly a better definition was needed for a species. Biologists have long recognised this fact and yet, over 150 years since Darwin published his great tome, we do not seem to be any closer to finding an all-encompassing definition of a species that works for all living organisms. For most multicellular animals the ‘biological species concept’ of Ernst Mayr is commonly used. It defines a species as a population of organisms which are able to interbreed successfully (i.e. produce fertile offspring) and are reproductively isolated from other populations. The problem with this definition comes from the annoying tendency of species to hybridise with other species. A famous example is the hybridisation between the endangered white-headed duck (Oxyura leucocephala) with the far more numerous ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis).

With the advent of phylogenetics in the 1950s a new concept, the phylogenetic species concept, was introduced. This defines a species as a group of organisms who share an ancestor. While it has benefits over the biological species concept it does have some unique problems mainly concerning the construction of the phylogenies. Under a strict application of the concept extinct species are not recognised, every distinctive geographical population becomes a species and it fails to describe reticulate evolution (cross-hybridisation).

I could go through every species concept explaining their pros and cons but that would make a very boring read and John Wilkins has already made a start that I feel unqualified to continue. Instead I want to focus on why this matters and what can be done.

Why should we care if we can’t define a species? There’s a lot of reasons but they can be broadly split into two camps: practical and philosophical.

On the practical side, the most basic reason for needing a species concept that works across the board is so that we can measure diversity. A lot of ecology boils down to comparing diversity, usually in the form of the number of species. If we can’t agree on how to recognise a species then how can we agree on how many species there are? A paper currently in press in TREE shows that despite six decades of effort we are no closer to a precise estimate of global species richness. Conservation efforts are beginning to focus on ecosystem-based management rather than particular species and the need to get the most from limited funds means the focus is on conserving highly diverse areas. The obvious corollary of this is that we need to be able to identify highly diverse areas which means identifying species.

The inability to consistently, unambiguously and impartially name species means that taxonomists have enormous power. The ‘lumpers vs splitters’ debate has rumbled on for decades. Some taxonomists prefer to name every new morphological variation as a separate species (the splitters) while others prefer that species remain highly variable (the lumpers). You may think that these arguments are largely confined to the past as genetic analyses can answer any questions we have, but you’d be wrong. It hasn’t been the panacea it was hoped to be and has caused just as many arguments and debates as traditional morphological classification.

On the philosophical side, admittedly a side not always favoured by scientists, we have to ask is there really such a thing as a species? It may sound like a stupid question on the face of it but when you start to really think about it, especially in the light of evolution (the ‘bump in the road’ I mentioned above), it becomes a bit more sensible. The problem with species is that we are trying to delineate something that does not have well-defined boundaries. It’s like taking a spectrum of blue to red and asking ‘where does the red stop and the blue begin?’. There’s clearly a blue section and clearly a red section (similar to the clear typological species of old). It’s the fuzzy area in the middle where the contention lies and it’s here where species concepts have difficulty, taxonomists equivocate and everyone gets confused and frustrated.

So what is the solution? Well, to be honest, I haven’t got one. I don’t even know if one really exists. I think we need to stop trying to draw lines where none exist but beyond that I’m stumped. Anyone got any ideas?

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image Sources: Wikicommons

Great dane and chihauhau from Duke University (http://bit.ly/1fFoBOR)

Red-blue spectrum modified from My Practical Baby Guide (http://bit.ly/1aXLnWw)

One Reply to “A Rose by Any Other Name”