Many linguists, psychologists, and anthropologists have discussed the concept of linguistic relativity: the relationship between the language a person speaks and the way that person thinks and views the world. As the primary language of the people of Ireland up until the 19th century, the Irish language (aka Gaeilge or sometimes Gaelic) is the repository of how people on this island thought and felt about the world around them for most of their recorded history. As part of this, Irish reflects the complex, colourful, and often idiosyncratic relationship that Irish people have had with the animals with which they share the island.

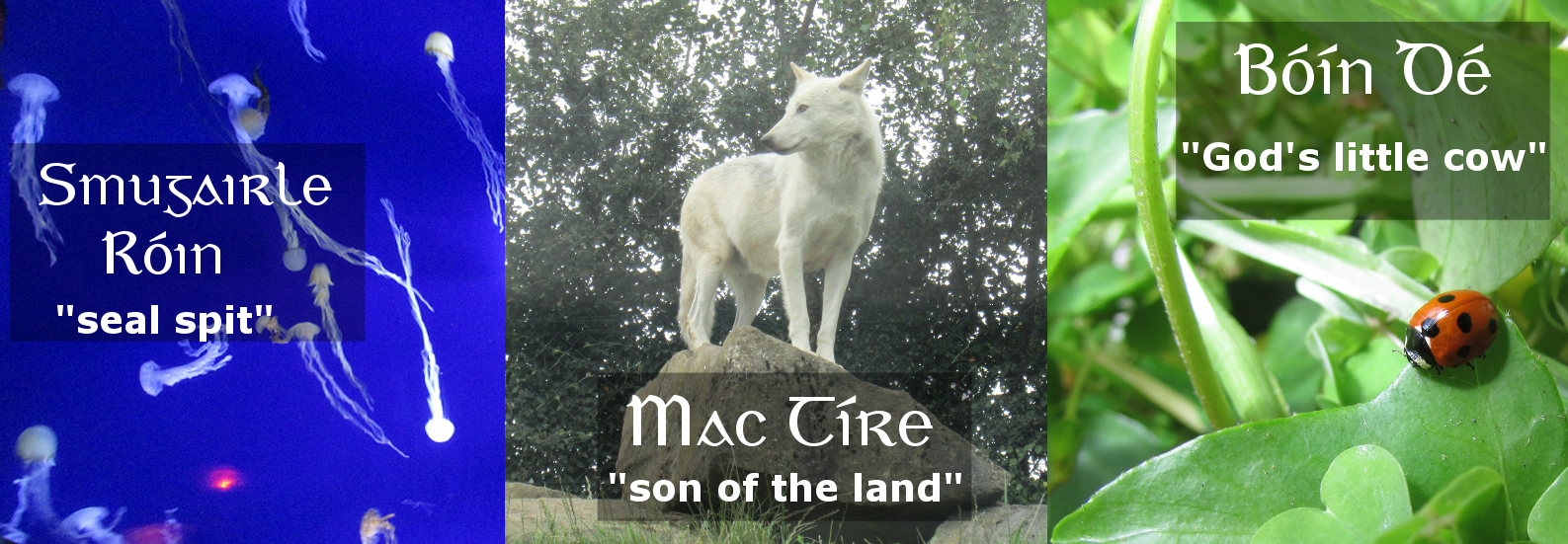

Names can show the people’s fondness for certain species, or they can highlight which aspects of an animal most stood out to them. For example, the ladybird, with its visually pleasing pattern of black spots on bright red elytra, has drawn the eyes of people all over the world and has an association with God or the Virgin Mary in many European languages, including both English and Irish. In Irish, it is known as Bóín Dé or “God’s little cow”, which is also the meaning of its Russian name, Божья коровка. Today, the ladybird’s bright, “bovine” pattern is seen as an example of aposematism, protecting the insect by signalling to potential predators that it contains bitter-tasting chemicals.

Other evolutionary adaptations are reflected in the names of other species: the little grebe is spágaire tonn, where Spágaire is a word for a person with big, clumsy feet or an ungainly way of walking, while tonn means wave. The little grebe does have big feet, or, rather, cartoonishly enormous ones. These look comical and seem clumsy on land, but in fact, they are a superb adaptation to the grebe’s aquatic lifestyle and enable it to do some seriously impressive diving. Here the Irish name is not only more colourful than the English one, but it also highlights a distinctive evolutionary feature in a memorable way. If the association with a clumsy human seems less than flattering, it is still dignified compared to the Irish name for jellyfish: smugairle róin, or “seal spit”. Note that the word smugairle can also refer to mucus dripping from the nose, so an alternative translation would be “seal snot”.

Whilst some animals (like the ladybird) have similar names in various languages, many others reflect a particularly Irish cultural context. The Wren (dreoilín in Irish) has many cultural associations in Ireland, including the custom of “hunting the wren” on St Stephen’s Day, and an even older association with the Celtic druids. Even its name might derive from a word for “druid”. The Goldcrest, meanwhile, is dreoilín easpaig in Irish or the “bishop wren”, as it is small and wren-like but has a crest reminiscent of a bishop’s mitre. This also shows a shift in influence in the language, from Celtic to Catholic. Elsewhere in Europe, people saw the crest as a crown instead, leading to the Goldcrest’s scientific name: Regulus regulus.

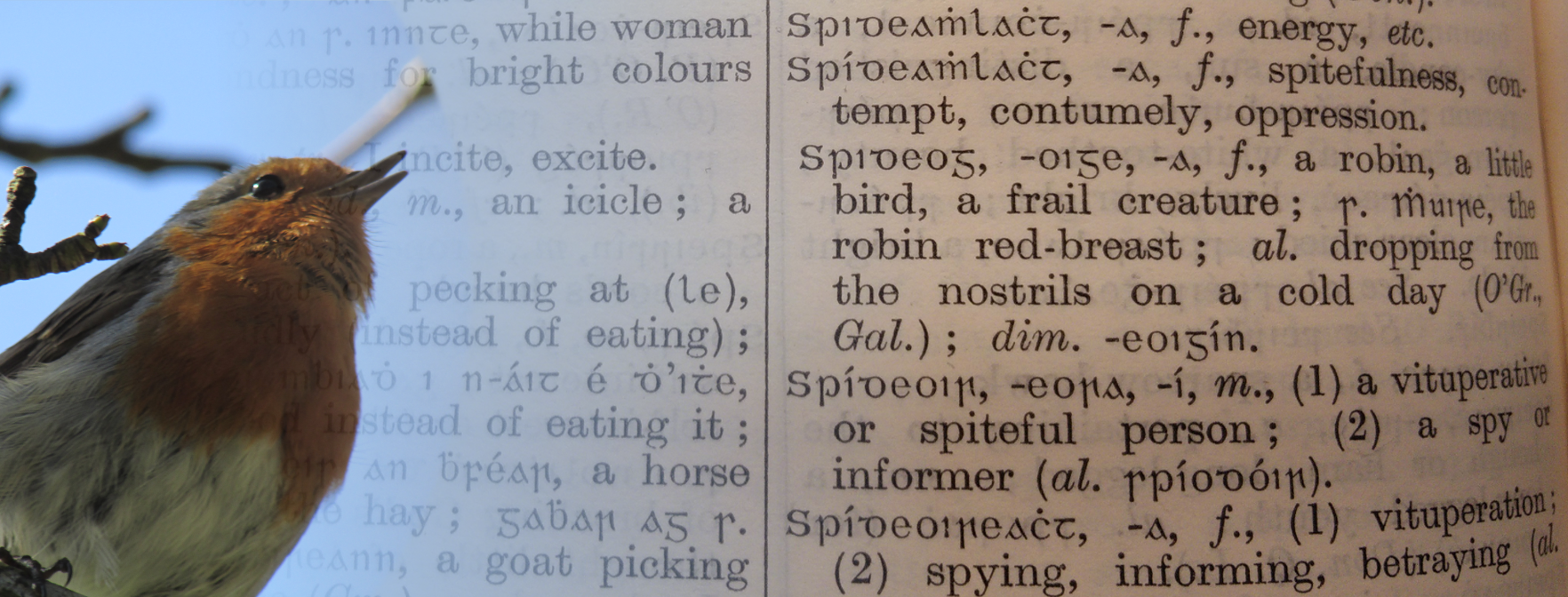

Like any language, Irish can have multiple words for the same thing. In some cases, dictionaries have recorded names that are no longer widely used, sometimes replaced by a more prosaic equivalent. The most commonly used name for the Stoat is easóg, which has no clear meaning besides “stoat” (or sometimes “weasel”). This name appears, for instance, in National Parks and Wildlife Service publications. But another name is beainín uasal, or “noble little lady”, perhaps related to the grace and power with which the tiny stoat hunts its much larger prey. Patrick Dinneen’s 1927 dictionary gives such gems as Séamas ruadh (modern equivalent: Séamas rua), a name for the Puffin which translates as “Red Seamus”. But by the middle of the century this bird had seemingly lost its Christian name as de Bhaldraithe’s 1959 dictionary omitted Séamas Rua in favour of the plainer, English-derived puifín and fuipín. This is not the only bird with a human name you’ll find on Irish shores: the Lapwing is Pilibín in Irish, or “Little Philip”. This name, which seems even more bizarre than “Red Seamus”, makes more sense with the context that pilibín is also a general nickname for a small thing, the way you might say “yoke” or “whatsit” in English. In other cases, a name has seemingly been traded from one species to another: Dinneen translates Scaladóir as “gannet”, but fifty years later Ó Dónaill will have it as “oystercatcher”, a different bird altogether. Dinneen also gives us a source for this name: Scala, meaning “a wind-blast or -squall”. In Irish, the suffix “-óir” is like “-er” in English, used for people who use or make a thing, so a scaladóir would be one who uses the wind squalls.

Whilst some species have lost their Irish names, we also have names that are left behind after the animal has died out. A classic example is the Irish word for wolf, mac tíre, which means “son of the land”. Though Ireland’s last wolf was killed in the 18th century, its evocative Irish name lives on in literature and placenames. When we are talking about conservation and extinction, the name of a species can be more than just an academic issue. Studies have shown that the general public will more readily engage with the protection of a species with which they have an existing emotional connection. Internationally, some conservation efforts have used “rebranding” to create a more favourable public image of a species, for example, referring to Lycaon pictus as the “African Painted Dog” instead of the “African Wild Dog” so as to make it sound exotic rather than feral.

In Ireland, we see large-scale projects to reintroduce “charismatic” species like the Golden Eagle and the Red Kite, while less attention is paid to small, brown, formerly abundant birds like the Corn Bunting as they decline and eventually die out. In an age when we are more disconnected from nature than ever before, most people don’t have an emotional connection to this kind of species, and many in the general public might not even know it exists. Even its name is forgettable. In the past, however, the Corn Bunting was known here as Gealóg Bhuachair, a gealóg being a “little bright thing” and buachar being a word for cow dung. This name is memorable, colourful and funny in ways that “Corn Bunting” is not. A name like “Little bright one of the cowpat” shows a clear emotional connection, one which is wry and affectionate. Though the bird no longer lives here, you can still read its Irish name in places like BirdWatch Ireland’s website, but if the reader does not understand what it means, then no emotional connection is established.

The same goes for any number of our threatened species. How many people know that Ireland is visited by the Pochard, a duck that is considered globally Vulnerable by the IUCN? Might more people take an interest if they knew it by some version of its traditional Irish name: lacha mhásach, or “duck with large buttocks”? Again, this name shows a jokey affection for the animal it describes, as do so many of the names discussed here.

With the threats faced by wild species all over the world, it is more important than ever that people take an interest in the wildlife around them. Ireland already has relatively few species of mammal, bird, insect, and plants, with even official documents of the Irish government describing the Irish fauna as “depauperate” relative to mainland Europe. Starting from a lower number of species, it becomes even more important to protect what we have. Ireland has a unique cultural treasury associated with its wild animals, which encompasses mythology, poetry, music, and more, but is perhaps most succinctly captured by the language used to describe the animals themselves. In other words, many countries have the Goldfinch and the Chaffinch, but only Ireland has the “woodland flame” and the “red king”. Our natural and cultural heritage developed side by side, and we have a duty to protect them both.

______________

About the Author

Fionn Ó Marcaigh is a PhD student in Nicola Marples’ research group in the Department of Zoology, Trinity College Dublin.He studies birds on Indonesian islands to uncover the factors underlying the evolution of new species, supported by the Irish Research Council. Find out more about his research here:

Website | TCD Zoology Profile

Twitter | @Scaladoir

Research Gate | Profile

LinkedIn | Profile

Related Posts

One Reply to “What’s in a name?”