This post is based on the paper ‘The avifauna of the forest mosaic habitats of the Mariarano region, Mahajanga II district, north-west Madagascar’, just published open-access in Bothalia: African Biodiversity and Conservation.

The header image by Jamie Grant-Fraser shows White-faced Whistling Ducks (Dendrocygna viduata) responding to the appearance of a Madagascar Harrier-hawk (Polyboroides radiatus).

Madagascar is a true jewel of Earth’s biodiversity. Its varied ecosystems are home to an awe-inspiring array of species and, unfortunately, are being lost at a horrifying rate. Last summer I spent 6 weeks working as an Ornithologist in the dry forests of the northwest of the country, surveying birds and teaching undergraduate and master’s students. I will never forget the time I spent in this biological wonderland, or the marvels of evolution I saw there. Our new paper describes the avifauna of the Mariarano region of dry forest and recommends its conservation as a BirdLife International Important Bird Area.

Madagascar is the 4th largest island in the world. Its tectonic journey separated it from Africa 165 million years ago and has kept it totally isolated from other landmasses for almost 100 million years. This long isolation has given evolution ample time to work on Madagascar’s biotas, leading to incredible levels of endemism: 84% of Madagascar’s land vertebrates are found nowhere else in the world. In its current spot in the southern Indian Ocean, Madagascar receives tropical trade winds on its east coast that have nurtured the growth of dense rainforests. The centre of the island forms a broad, high plateau which shades the western coast. This has given Mariarano and the rest of western Madagascar a very different deciduous dry forest ecosystem, of thin-branched trees growing in sandy soil and sparse lakes that attract huge flocks of waterbirds. Both rainforest and dry forest are under severe threat, as more than 40% of Madagascar’s forest cover has been lost since 1950.

Numerous conservation organisations are striving to protect Madagascar’s nature, while scientists try to understand it while they can. This is how I came to work as an Ornithologist with Operation Wallacea, who partner with local organisation Development and Biodiversity Conservation Action for Madagascar (DBCAM) to conduct research in the dry forests. Madagascar’s biodiversity has suffered great losses, but there are many passionate and knowledgeable people fighting for it, both Malagasy and vazaha (foreign).

My little 2-man tent was my only home for the whole 6 weeks, as I moved between dry forests near the villages of Mariarano, Matsedroy, and Antafiameva. Brown lemurs and Coquerel’s sifakas climbed above (and occasionally rained droppings on my flysheet), I fell asleep most nights to the rhythmic song of the Madagascar Nightjar, and one night I had to repel an invasion of near-microscopic ants that had chewed a fine mesh of holes into my floor and made a system of tunnels in my foam mattress. Bird surveying would begin before the sun rose, so the other ornithologists and I would navigate the forests by the light of head torches, students in tow. We surveyed birds through mist-netting similar to that carried out by TCD Zoologists in Sulawesi, and by conducting point counts at fixed locations along a transect. Our efforts produced data for one of the longest-running ornithological studies in western Madagascar, and this first list of Mariarano’s avifauna. Along the way, new populations were noted of species like the Endangered Van Dam’s Vanga. Many of Earth’s most biodiverse regions still lack full information on what lives where, as seen in previous TCD work on the birds and mammals of Indonesian islands.

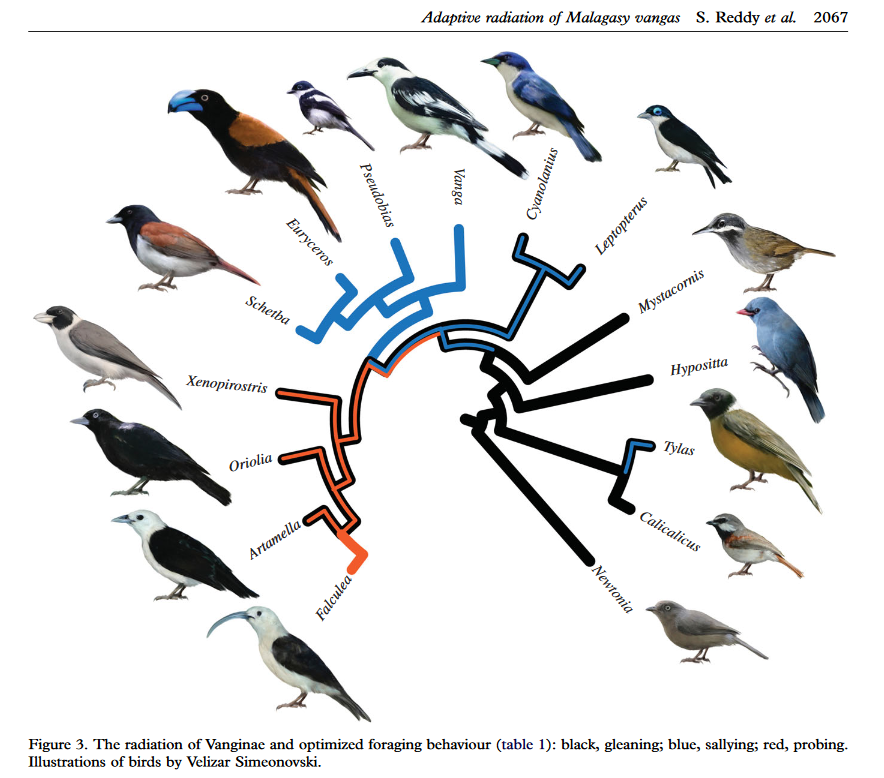

No matter whether one is most interested by birds, reptiles, mammals, insects, or plants, Madagascar is transfixing. It is not just that you can look at any given scene and know that most of the organisms you see are unique to Madagascar, but also that these organisms are so visibly peculiar, so enchanting in and of themselves. Among the birds, the cuckoo roller (whose strange squat form I sadly never saw) and the pheasant-like mesites each represent an endemic order, entire branches of the avian family tree that are exclusive to Madagascar. Other specialities include the adorable and diverse vangas, who have evolved variations in bill morphology to rival Darwin’s finches, and the couas, members of the cuckoo family with distinctive blue skin around their eyes.

Though I was there to study the birds, I could not help but spend time admiring Madagascar’s other fauna. Endemism is even more striking in those animals that aren’t able to fly: It is staggering to think how one colonisation by a bushbaby-like primate could lead to the radiation of over 100 charming species of lemur. Today, these primates exhibit forms as diverse as the ecological niches they fill, from tiny mouse lemurs that could sit in a teacup to enormous indris, whose haunting song can be heard floating above the rainforest canopy from up to 4km away. Madagascar’s carnivores are even more different from one another, to the point that we did not know they belonged in the same family until recently.

From the time I first set my heart on becoming a zoologist, Madagascar was a place I longed to visit. I hope I can return to the Great Red Island someday, and that its beautiful, peculiar, perfect forests will still be there when I do.

Thanks to all of the other members of the Ornithology team, from whom I learned a lot: Solohery, Bruno, Ricky, Malala, Gael, and Anja.

______________

About the Author

Fionn Ó Marcaigh is a PhD student in Nicola Marples’ research group in the Department of Zoology, Trinity College Dublin. He studies birds on Indonesian islands to uncover the factors underlying the evolution of new species, supported by the Irish Research Council. Find out more about his research here:

Website | TCD

Zoology Profile

Twitter | @Scaladoir

Research Gate | Profile

LinkedIn | Profile

All photos taken by the author unless otherwise specified.