The most iconic examples of sexual dimorphism are found in birds. Birds are probably many people’s introduction to this concept in the natural world, when brought to the park as a child and shown the difference between male and female mallards. But sexual dimorphism can be much more subtle than that kind of difference in colour (called dichromatism, and seen also in peacocks, pheasants, sparrows, and many more). Our new paper, just published by the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation in their journal Biotropica, shows that sexual dimorphism can be missed in some birds even when it is important to their ecology and evolution.

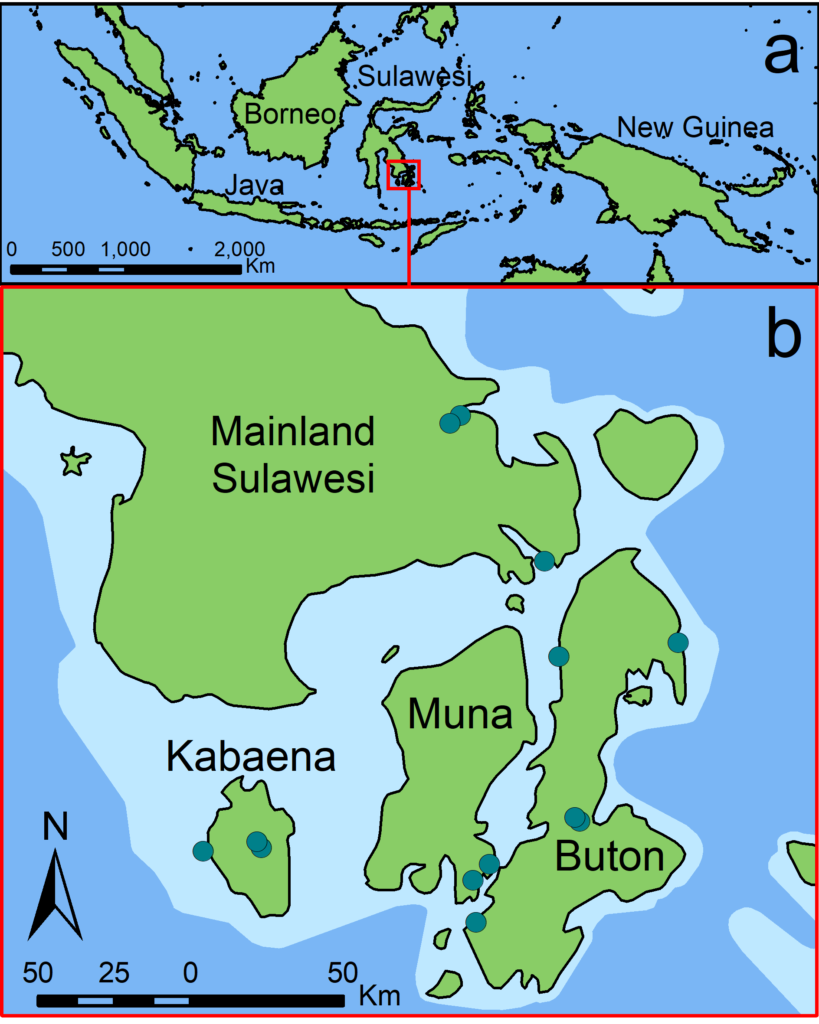

As tropical songbirds go, the Sulawesi Babbler (Pellorneum celebense) is not the most ostentatious. Both males and females are a dull brown in colour, and the species spends most of its time hiding in dense bushes. Even its song is somewhat basic, described as “short variable phrases of liquid fluty melancholy whistles”, though they make up for this by singing loudly and often (babbling, if you will). Our research group sampled these birds using mist nets during multiple field seasons on the Indonesian islands of Sulawesi, Kabaena, Buton, and Muna, taking measurements and DNA samples (and then letting them go!) as part of our evolutionary studies in the region.

While birds are better understood scientifically than many other animal groups, there are still gaps in our knowledge, especially around species that inhabit small areas of the tropics or are shy and hard to observe. The Sulawesi Babbler fits both criteria, as do many of the other babbler species found on islands across Southeast Asia. The evolutionary tree of this family is so complicated that it is still being figured out by scientists today, and there’s still plenty we don’t know about the natural history of particular babbler species. This is a growing problem when so many of their habitats are under severe threat: for example, several of the islands we visited are facing ecological devastation from large-scale nickel mining.

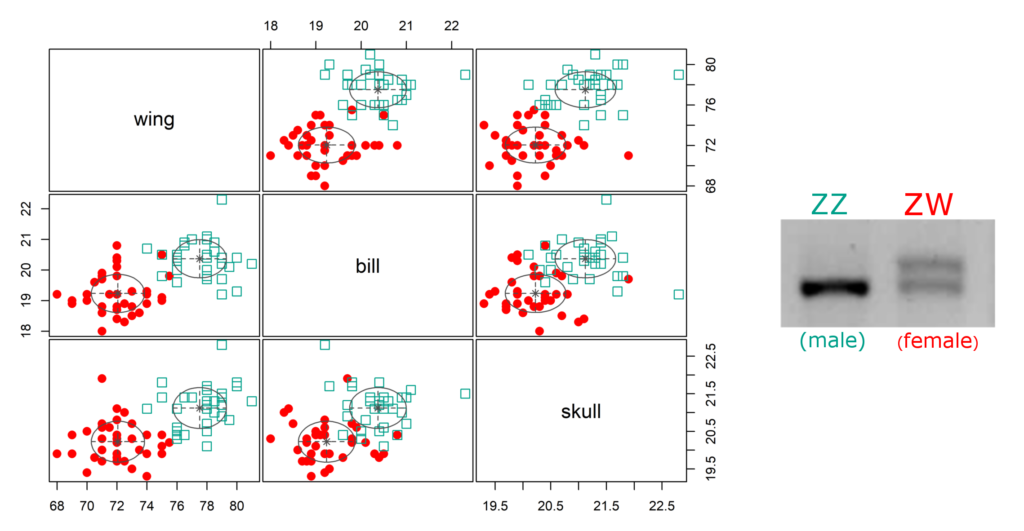

Analysing our data using clustering models, we found that there were two groups in the Sulawesi Babbler population, with half of the birds having longer bills, wings, and skulls than the other half. Although no sexual dimorphism had been described in these birds or their relatives, this pattern suggested to us that one sex was probably larger than the other. Using genetic sexing techniques, we were able to demonstrate that, indeed, the larger birds were the males and the smaller ones were female. Sex determination in birds, as in humans, is based on combinations of sex chromosomes, with ZZ chromosomes causing a bird to develop into a male and ZW as female. Because of this, we were able to sex our babblers by examining their DNA on electrophoresis gels, so that birds showing two bands were ZW (female) and birds with one stronger band were ZZ (male).

When we miss traits like sexual dimorphism in a species, it can obscure important aspects of their evolution and ecology. In this case, once we realised that our babblers were sexually dimorphic, we were able to test an evolutionary theory that states that dimorphic species should become more strongly dimorphic on smaller islands, preventing the males and females from competing with each other for scarcer resources. Our data bore this out, with the male babblers being even larger and females even smaller on islands than they were on the Sulawesi mainland. This is especially interesting as, while this is often observed on very remote islands, our islands were all connected to each other when sea levels were lower during the last ice age, so this difference must have evolved quite rapidly. Any trait that evolves so quickly must be undergoing quite strong selective pressure, revealing its importance to the species and its ecology. It leads one to wonder what else we don’t know about the wonderful species inhabiting the tropics, and whether we can learn it before it is too late.

To find out more, check out our full article in Biotropica, ‘Cryptic sexual dimorphism reveals differing selection pressures on continental islands’.

Reference:

Ó Marcaigh F, Kelly DJ, Analuddin K, Karya A, Lawless N and Marples NM (2020) Cryptic sexual dimorphism reveals differing selection pressures on continental islands. Biotropica 2020; 00: 1– 9. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12852

Header photo of a Sulawesi babbler by Emma Shalvey.