A warm welcome back to all our readers! The new year is now well and truly upon us and we hope you’ve all had a safe and energised return to work. This blog is written by Fionn Ó Marcaigh, summarising his new paper. Congratulations Fionn and we hope our readers enjoy learning about your research as much as we have! So without further ado…

Science is about making observations from the natural world, drawing up hypotheses to explain the patterns you’ve observed, and then testing these hypotheses by experimentation. We tend to imagine scientists in white coats doing experiments in the lab, but our understanding of evolution also owes a lot to work done in “natural laboratories” like islands and other isolated habitats, where evolution has taken place under different conditions. Our new paper, just published Open Access by the International Biogeography Society in their journal Frontiers of Biogeography, has used an important natural laboratory in Southeast Asia to test a classic hypothesis based on a bird called the Island Monarch (Monarcha cinerascens). We’ve made observations that contradict parts of the hypothesis and discovered a possible new species in the process!

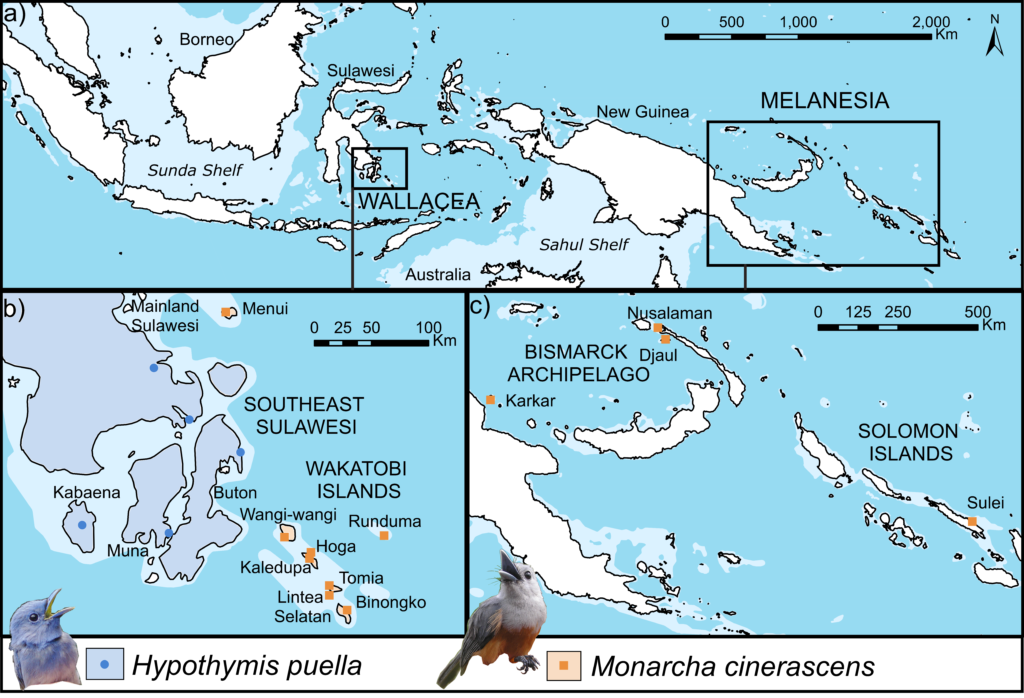

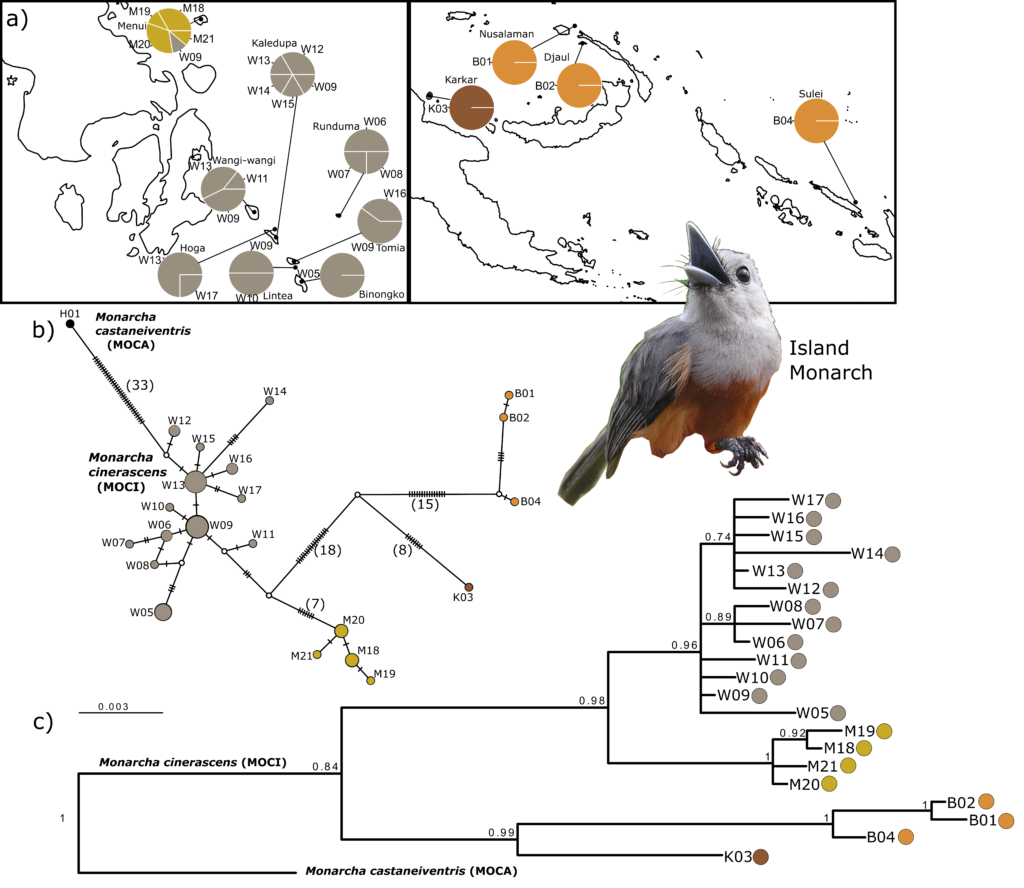

Our natural laboratory was a collection of islands around a region known as Wallacea in central Indonesia (see map below). Named after Alfred Russel Wallace, this is where he co-discovered evolution by natural selection while travelling around islands of all shapes and sizes, with the waters around them being so wide and deep that most species have trouble crossing them. Some organisms are better at crossing these barriers than others, with the Island Monarch thought to be particularly adept. As its name suggests, the Island Monarch is one of the kings of small islands. It can be found all the way from the islands off Sulawesi in Wallacea, to the farthest reaches of the Melanesian islands east of Papua New Guinea, but is missing from large islands like Sulawesi and New Guinea themselves.

In his pioneering biogeography work in Melanesia in the 1970s, Jared Diamond observed the curious distribution exhibited by the Island Monarch and several other birds. He called these species “supertramps”, evoking the hobo-turned-poet WH Davies and his “Autobiography of a Super-Tramp” as well as a certain rock band of the era. As these birds were able to colonise small, remote islands where other species did not reach, they must have strong abilities for flight (aka dispersal or “tramping”). Diamond hypothesised that this was an adaptation to the conditions on these small islands, which are remote and subject to so much disturbance that a bird will have an advantage if it can re-colonise quickly. But why are they missing from the large islands in between the small ones? Diamond’s hypothesis had to do with competition: he proposed that the supertramps have made such heavy evolutionary investment in dispersal ability that they can’t compete in other ways, and so they end up excluded from larger islands with more species on them.

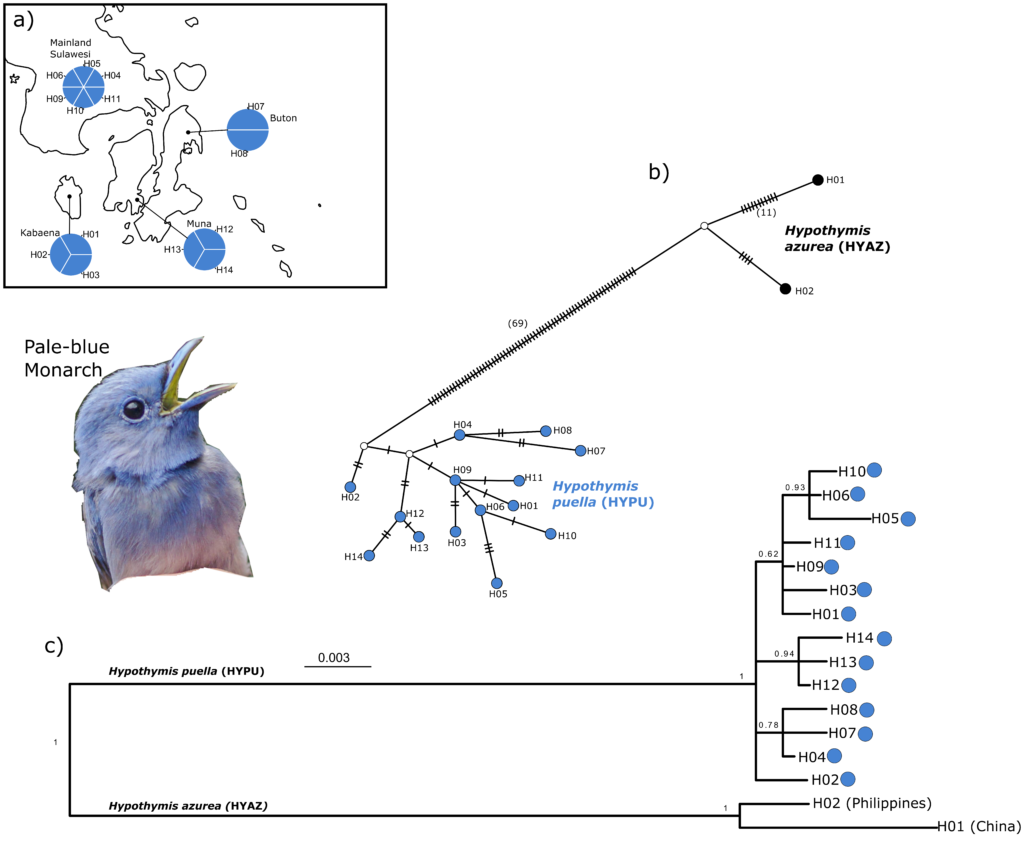

Enter the Pale-blue Monarch (Hypothymis puella), the Island Monarch’s closest relative in this part of Wallacea. The Pale-blue Monarch lives on Sulawesi and the other large islands off its coast, from which the Island Monarch is missing, in keeping with the competition hypothesis. Our study, undertaken in collaboration with Universitas Halu Oleo, sampled the DNA of Island and Pale-blue Monarchs to see how the populations have been evolving. Surprisingly, we found that the Island Monarch’s supertramp abilities haven’t stopped it from splitting into multiple distinct populations.

If the Island Monarch evolved a “supertramp” lifestyle to adapt to conditions on small islands, we would expect it to keep tramping between these islands, leading to a well-mixed population. Meanwhile, if the Pale-blue Monarch showed structure on the larger islands where it lives (which are less isolated from one another than the small islands where the Island Monarch lives), then this would give more support to the idea that its competitive ability comes at the expense of dispersal ability.

Our results did not support either of these expectations! Not only are the Island Monarch populations of Wallacea and Melanesia strongly genetically divergent from one another, to the point that they probably represent two separate species, but there are even unique populations on islands within each region, separated by relatively narrow stretches of water. The supertramp does not keep tramping and in fact seems to transition to a normal resident bird species. The Pale-blue Monarch, for its part, does have a well-mixed population (though it has shorter distances to cross). So despite being able to out-compete the Island Monarch on larger islands, the Pale-blue Monarch’s dispersal abilities still seem to be better than some other birds that live on these same islands.

So what causes a supertramp to settle down like this? Scientists who looked at other supertramp species suggested that they would lose their dispersal abilities over time, as these would be selected against in more stable environments in particular. We tested this in our natural laboratory by measuring the wings of our monarchs to calculate their “dispersal index” and modelling this against their genetic divergence and the size and elevation of the islands where they lived. Although they do diverge more strongly on the larger and higher (i.e. more stable) islands, we found no evidence that the Island Monarchs there are actually losing their dispersal abilities. They simply aren’t using them!

In another part of his biogeography work, Diamond described a phenomenon like this in other birds, terming it “fear of flying”. It goes to show how difficult it can be to conduct science on the natural world: you can observe that a bird is good at flying, then make all these hypotheses based on its flight abilities, only for it to refuse to fly for its own behavioural reasons. You can lead a horse to water…

To find out more, check out our full article in Frontiers of Biogeography, ‘Tramps in transition: genetic differentiation between populations of an iconic “supertramp” taxon in the Central Indo-Pacific’.

Reference:

Ó Marcaigh F, O’Connell DP, Analuddin K, Karya A, Lawless N, McKeon CM, Doyle N, Marples NM, Kelly DJ (2022) Tramps in transition: genetic differentiation between populations of an iconic “supertramp” taxon in the Central Indo-Pacific. Frontiers of Biogeography 14(2); e54512. https://doi.org/10.21425/F5FBG54512

Thank you to Emma Shalvey for the use of her Pale-blue Monarch photo.

Updates:

Call for contributors

We are really excited for the year ahead and part of that includes hearing what you have to say! With that in mind we are always looking for new (or repeat) contributors so please let us know if you’d like to be involved, whether you have your own idea for a blog post or you’re interested in writing one but need some inspiration, we’re always happy to workshop new posts with you! Here’s a few idea that might inspire you:

- Modern Women in Science: write a profile about a scientist that you work with, want to work with, inspires you, has been a pioneer in your field etc.. any woman scientist qualifies (even yourself!)

- Did you move to Ireland from another country? Why not write about your experience of different approaches to research in different countries?

- Are you new to your position? What advice would you give someone coming into a similar position?

- Have you recently read a paper you thought was very interesting? Tell us about it! (also valid for books, news stories, documentaries, movies etc… – must be eco/evo related)

- Have you had research assistants working with you recently? Why not ask them to write a piece about their experience?

These are just a few ideas that might inspire you but the list is, of course, non-exhaustive! Blog posts don’t have to be long and daunting, 500 words and a couple of photos on a subject you enjoy makes for a great read and really helps with engagement, so give it a try!

Reminder: Photo Competition Deadline upcoming

The EcoEvo PHOTO COMPETITION 2022 is rapidly approaching. Thank you to everyone that’s submitted so far – we’re already blown away by the variety and quality we’ve seen! Those of you that have yet to submit a photo, remember the deadline for submissions is Friday the 21st of January.

As COVID has prevented many of us from engaging in fieldwork this past year (which is often the most important source of photos for this competition!), the criteria for photos have been broadened slightly – any photos reflecting the themes of the EcoEvo blog (research, ecology, and evolution) can be entered, from any year, and you are encouraged to interpret this creatively (but – depending on how creative you’ve been – remember to supply a brief description of your photos). The winner will have their photo displayed as the blog banner for the next year! To enter you must be a member of NERD club and should email submissions directly to us at ecoevoblog@gmail.com.

One Reply to “Tramps in Transition: Wallacea’s monarch flycatchers and their evolutionary natural experiment”