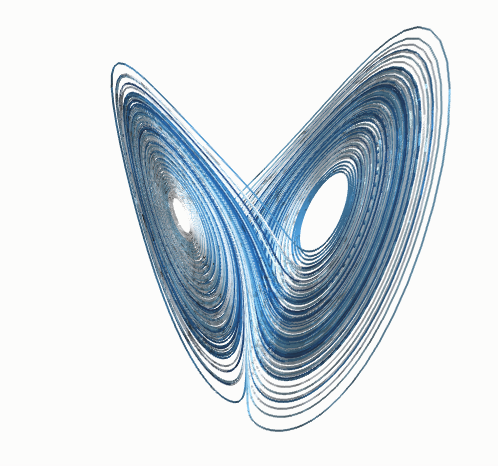

A new paper has been published in Science by George Sugihara and colleagues, which is an immediate contender for the most insightful paper I’ve ever read. In the paper they outline a new method, which they dub ‘Convergent Cross Mapping’ (CCM), for detecting causality between variables using time series data. Not only does CCM allow for the detection of causality but also its directionality. The method takes us well beyond the previous confines of Granger causality (which requires the assumption that systems are linear, or are showing linear behaviour near an equilibrium), and allows us to tease out causality in systems that show non-linearity and chaos. As examples of possible applications of their method the authors address two classic causality problems:

Predator-prey dynamics of Didinium and Paramecium. The authors show that there is bidirectional causality in this classic predator-prey system, but that top-down control is stronger than bottom up control (i.e. Didinium has a larger effect on the Paramecium population than vice-versa).

Dynamics of Pacific sardines and anchovies. There has been a long-standing debate about the cause of alternating dominance between sardines and anchovies in the Pacific. Some arguing that competition between the species is the driver, while others claim the pattern is caused by differing responses to temperature. The authors weigh in on this debate by showing that, while sardine and anchovy abundance is negatively correlated, this is a mirage as there is no causation in either direction. The authors also unambiguously show that sea surface temperature does causally affect the abundance of both species, indicating that climate is the main driver.

I think this method will be absolutely invaluable to future studies, and for me has already proved its worth from the results the authors present. The videos below are from the supplementary information of the paper and explain the method simply using beautiful illustrations.

Author

Luke McNally: mcnall[at]tcd.ie

Photocredit

Wikimedia commons