Pterosaurs are the largest animals to have ever flown. Some species had wingspans exceeding 10 metres dwarfing the largest avian challenger. It must have been quite a sight to see one of these things blocking out the Mesozoic sun. But there have been niggling doubts about the ability of the larger representatives to fly. Will we have to re-evaluate our mental image of the Mesozoic and ground our pterosaurs?

Flight is no easy thing for an animal. It makes all sorts of demands on the physiology, morphology and ecology of the creature trying to take to the air for a living. With every added kilo a bit more lift has to be generated, for every extra wing flap more energy is required. Still, most pterosaurs look like they fit the bill. Their skeletons were heavily pneumatized and they had a hyper-elongated fourth finger from which they could support a membranous wing.

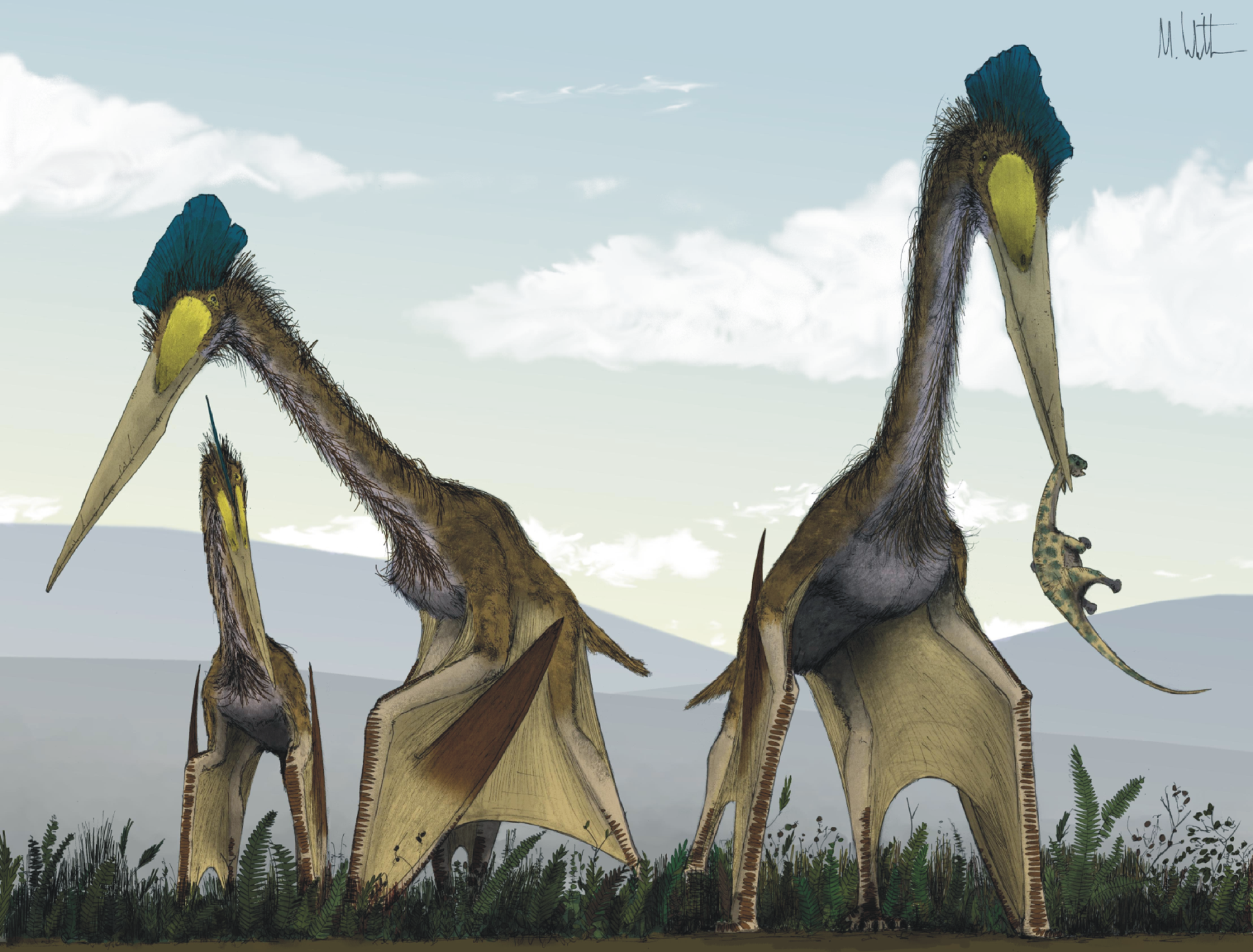

The problem arises when we look at the giant pterosaurs especially the Azhdarchidae family which houses the biggest species like Quetzalcoatlus northropi and Arambourgiania philadelphiae. One analysis gave a mass estimate of half a tonne for Quetzalcoatlus n., which would almost certainly render it flightless. Other researchers point to the terrestrial adaptations seen in this family and of course we can see many instances of birds who have become secondarily flightless. A size gap was pointed out where there exist small pterosaurs and giant ones but no intermediates which was said to mirror the pattern of flying birds and flightless ratites. Then there is the taphonomic bias seen in the fossil record whereby most of the Azhdarchid skeletons are found in terrestrial environments.

But not all palaeontologists are convinced by these arguments, pterosaur specialists Mark Witton and Michael Habib have taken each one of these lines of evidence to task and found them wanting.

Firstly, while most of the fossils have been found on land this doesn’t mean the animals were terrestrial, many bird species fly exclusively over land, so that bias is neither for nor against.

Secondly, the suggested size gap looks like an artefact in the fossil record which has been filled with intermediate forms.

Perhaps the most convincing piece of evidence in favour of flightlessness are the huge mass estimates. A half tonne reptile is going to struggle to get airborne. But this figure is beginning to look like an overestimate, the result of distorted fossils and inappropriate scaling techniques. A more lightweight figure of 240 kg looks to be more realistic when these biases are accounted for.

What of the terrestrial adaptations? Well, there is no issue with the animals being adept on the land while still being able to fly. Indeed the authors above argue that large Azhdarchids occupied the niche of modern day ground horn bills or storks both of which are well adapted to the land while still being able to fly.

In the end it looks like giant pterosaurs did take to the skies. Piecing together the mode of life of long extinct species is never easy but it’s not impossible.

Author

Adam Kane: kanead[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Witton MP, Naish D (2008) A Reappraisal of Azhdarchid Pterosaur Functional Morphology and Paleoecology. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002271