Adam raised the point of science communication in his last blog post of how science should be communicated to a mainly interested and receptive public. The main question when thinking about science communication is “how should we do it?” However a second question, arising from this one would be “who should do it?”

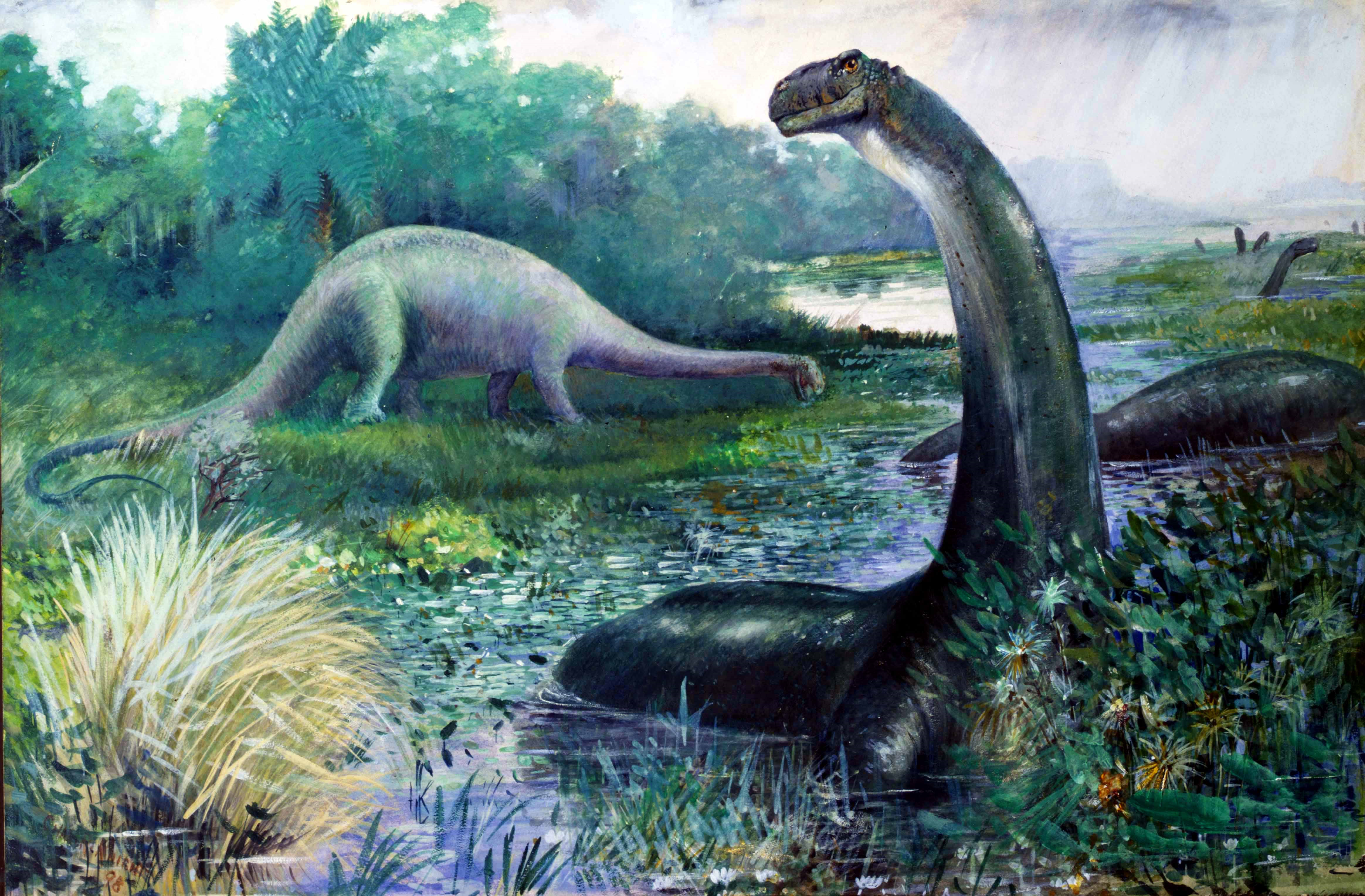

I believe having an interest in popular science is the first step for starting a career as a scientist. Personally, I was influenced by Jurassic Park, which gave me the idea that in a distant future I would (could) become a paleontologist. I believe this influence is shared by a vast majority of young paleontologists of this Bakker dinosaur’s revolution generation. So, to me, even if Jurassic Park bent some scientific rules (the most obvious one being bringing stones to life), the film created a renewed interest in its related field of palaeontology.

Ok, so that’s a good reason for popularizing science then? It’s not that easy. A fairly large amount of scientists will always look at such attempts to popularize science as a “bastard” child of the scientific adventure, a kind of side effect that makes scientists, in the best case, smile ironically. In the worst case though, they think it propagates massively erroneous ideas: like the one I pointed out above or -another that “makes me smile ironically” – that paleontologists are Indiana Jones-style adventurers that wander around the world and from time to time brush the sand and discover how velociraptors (read Deinonychus) were talking to each other.

Richard Whitley in his book, Expository Science: Forms and Functions of Popularisation, summarises the idea by writing that: “popularization is not viewed as part of the knowledge production and validation process but as something external to top research which can be left to non-scientists, failed scientists or ex-scientists as part of the general public relations effort of the research enterprise.”

This vision of popularizing science is linked to the idea that an increased output of popular science leads to a fatal decrease of legitimate and accurate scientific progress. This is known as the ‘Sagan Effect’ after Carl Sagan and the erroneous claim that his legitimate scientific output decreased after the initiation of his popular science TV series: Cosmos.

Can one popularize science and actively do science?

When one has a look at the actual numbers (scientific articles published vs. popular articles published), one expects that if popularizing science is reserved for “failed scientists”, people publishing more popular articles will publish fewer science articles. Michael Shermer, in his paper published in Social Studies of Science in 2002, brings down this popular belief by calculating the actual numbers of scientific papers published by these popular science writers.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

As a base line, while the four PIs publishing on this blog all take part in extra curricular activities, they are primarily research scientists. Last year, they published all together 22 papers which gives a respectable average of nearly one paper per PI published every two months! In contrast, if you look at the great popular science writers of the end of the last century (say Carl Sagan or Steven Jay Gould), during their massive and influential popularization of their fields, they produced an average of one paper per month for Sagan and nearly two papers a month for Gould (and that for 35 consecutive years!). So they seem to have it all: “legitimate“ science output and successful careers as science communicators. Just looking at these figures, the myth of the trade-off between popular science writing and actual scientific production is just, as Shermer describes it, “a Chimera”!

Can one popularize science and actively do science?

Yes. And to go back to my first point, with Jurassic Park (which, in comparison to Gould or Sagans’ popular work can easily be classified as a “bad” way to do it), I believe that popularizing science is not a problem: in an altruistic world, scientists should focus on contributing to the advancement of their field by any means possible, not exclusively on their own amount of publications. Thankfully, most scientists manage to combine both popular communication and research output efficiently. I think that one important and still altruistic way to contribute to the advancement of a field is definitely science popularization. Richard Whitley says that “by successfully combining claims to universal validity and social utility through popularization, [Sagan and Gould] laid the foundation for the present domination and expansion of the sciences.” These contributions have a real long-term benefit to the advancement of the field. Firstly, the ideas of the authors of popular science become fixed in the public consciousness and secondly (most importantly to me), they inspire new generations of scientists that will, later on, personally contribute to the advancement of their field.

Is this bad for “legitimate” scientific production? Not at all! By popularizing evolution in a realistic (or perhaps not so realistic) way, Gould and Jurassic Park spark the interest and imaginations of the next generation of potential scientist who, through their research, will make direct contributions to scientific research!

It’s a positive feedback cycle: excellent scientists generate good science communicators; good scientific communication generates scientific interest and curiosity; scientific interest produces scientists and some of these scientists will go on to become good scientific communicators…

Author: Thomas Guillerme, guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme

Image Source: wikimedia commons