Last week our newest EcoEvo@TCD paper came out in PRSB (it will be Open Access soon but currently it’s behind a pay wall – feel free to email me for a copy in the meantime. Also code to fit multiple PGLS models can be found here). This paper is exciting for me for two reasons – firstly because the science is really cool, and secondly because of how it came about. Today I want to focus on the paper itself, and in my next post I will explain how this collaborative project started.

People are fascinated by death, perhaps because as Benjamin Franklin said, “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”. In classical times, people believed you could live forever if you could find the “Fountain of Youth”, whereas today many scientists are looking to the natural world for ways to extend human lifespans.

The natural world is a great place to look for answers about death because there is huge variation in lifespans among living things. Even if we ignore single-celled creatures, lifespans still range from three days in gastrotrichs – a strange group of animals found in the spaces between particles of sand and mud and in water – to 5050 years in the bristlecone pine. [As an aside – we know the age of the bristlecone pine in question because someone took a core from the tree and counted its annual growth rings. We also know the exact date the tree died because taking the core killed it!].

You could argue that this lifespan variation only exists across broad taxonomic scales, but even just within birds and mammals, maximum lifespans range from around 2-3 years in forest shrews and small perching birds, up to 211 years in the bowhead whale. [Another aside – this estimate was made using a piece of harpoon found embedded in the carcass of the whale. The harpoon carried a maker’s mark for a company that hadn’t been in action for over 100 years! Combining this information with how big the whale would have been to be worth harpooning, scientists came up with the 211-year estimate]. And there’s lots of variation within mammals and birds too, with parrots and elephants living up to 80 years, geese 70 years, horses 50 years, and even chickens can live to be around 30 years old – older than dogs, sheep and goats! At the other end of the scale, things like mice and rats tend to live less than five years in total. The question for a biologist therefore becomes “How can we explain this variation?”

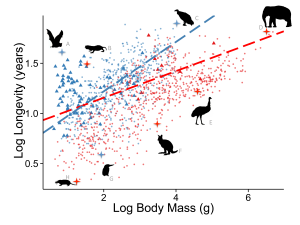

The first, and most obvious, explanation is that lifespan increases with body size. This makes intuitive sense to us because we’ve seen it in our childhood pets – our hamster dies at 2 or 3 years old (barring unfortunate accidents with cats, heavy furniture or Freddy Starr**) but the family dog or cat lives into its teens. This is also something that has been known in mammals and birds for a long time. However, body size only explains around 30% of the variation in lifespan for mammals and birds, and some species live far longer than you’d expect given their body size (see Figure 1 from the paper below).

For example, naked mole-rats should live around five years but actually can live up to 28 years (this record is from a male naked mole-rat that we affectionately know as the “rotting sausage” in the department)! The record holder is Myotis brandti, a little brown bat that weighs as much as a mouse but lives up to 40 years!!! So ten times longer than expected given its body size. Again this leads us to ask “Why do some animals live so much longer than expected given their body size”?

We hypothesized that the answer might be connected to the levels of extrinsic mortality – that is death caused by external causes like predators, poor weather conditions, food shortages etc. – experienced by different animals. Animals experiencing a high likelihood of death will be under selection to breed as rapidly as possible because they are unlikely to survive long enough to get another chance! Conversely, animals experiencing lower levels of extrinsic mortality will be under selection to invest more energy into raising fewer, higher quality offspring, develop immunity from diseases and maintain their bodies, and thus have a longer lifespan than animals under higher threat of death.

We decided to test if this was the case by looking at four factors we thought could reduce extrinsic mortality for a mammal or bird as follows. (1) Flight. Flying animals can escape predators and leave unfavourable conditions so should have lower extrinsic mortality than non-flying species. (2) Burrowing. Animals that live in burrows should also be able to escape predators and leave unfavourable conditions more easily than non-burrowers. (3) Living in trees. Animals living in trees should be safer from predators than those living on the ground. (4) Being active in the dark. Animals that only come out at night should be better camouflaged from predators than animals active during the daytime.

We tested these ideas using over 1300 species of mammals and birds. The data came from online databases and various sources in the literature, and we corrected for phylogeny using phylogenetic Bayesian mixed models (see the paper for details). We found that species that live in trees or burrows, or that possess the ability to fly, lived far longer then expected for their body size. Usually people fit these models to mammals, bats and birds separately, but we wanted to split species ecologically rather than taxonomically. Interestingly we also found that the usual slope of the relationship between body size and lifespan is actually different in flying versus non-flying mammals and birds, with flying mammals and birds showing a greater increase in lifespan for a given body size increase than non-flying species (see Figure 1 from the paper and above). Another interesting result this method revealed is that bats in general are not exceptionally long lived for their body size, given that they can fly. Most bats actually fit the regression line very well, so we can think of them as “furry birds” for the purposes of their lifespans!

Our models do not explain all variation in lifespan among mammals and birds. Many of the explanations for the remaining outliers (including various bats especially Myotis brandti, the naked mole-rat, pelagic seabirds, crows and even a few perching birds) are probably idiosyncratic. Suggestions include protected nesting areas, sociality, brain size, hibernation, latitudinal distribution and (of course!) various sampling effects. But we conclude that if we really want to look to the natural world for help extending human life, we shouldn’t just focus on bats and naked mole-rats. Our results also highlight the importance of understanding how evolution and has shaped the lifespans of animals today, rather than merely focusing on the genetic basis of ageing.

Author: Natalie Cooper, ncooper [at] tcd.ie, @nhcooper123

*Yes “Dying without wings” is a pun based on a WestLife song. Because if you can use a Westlife pun, you should use a Westlife pun. Except in the USA where no-one has heard of Westlife, and explaining the concept of an Irish boyband is really quite difficult! Weirdly enough in Madagascar we met a 23 year old Malagasy student who loved Westlife; so this really is a universal pun that just doesn’t work in the USA…

**Yes I am using a joke from 1986…I’m totally down with the kids…

One Reply to “Dying without wings* Part I”