As mentioned previously on the blog, Andrew Jackson and I started a new module this year called “Research Comprehension”. The module revolves around our Evolutionary Biology and Ecology seminar series and the continuous assessment for the module is in the form of blog posts discussing these seminars. We posted a selection of these earlier in the term, but now that the students have had their final degree marks we wanted to post the blogs with the best marks. This means there are more blog posts for some seminars than for others, though we’ve avoided reposting anything we’ve posted previously. We hope you enjoy reading them, and of course congratulations to all the students of the class of 2014! – Natalie

Here’s thoughts from PJ Boyce and Joe Bliss on Dr. Frederic Marion-Poll’s seminar; “Why do we avoid bitter molecules (and why do flies avoid them too)?”

———————————————————————————-

A Bitter Taste for Deadly Sweets!

PJ Boyce

Have you ever held a cockroach in your bare fist? Have you felt its wings flicking against the inside of your hand? Its feet sticking to your skin? Personally, I’ve touched and held a lot of weird and wonderful things but never have I been so thoroughly disgusted as when I held a cockroach. Its such an…icky…creature! So why is it in this modern age of mass extinctions, that the cockroach has managed to persist, even considering the considerable amount of effort on our part to exterminate the little devils! I can’t answer that. What I can do is explain yet another way in which these tough little guys are managing to foil us again: They are avoiding our poisoned bait traps! How? By changing how they think about them!

Of course, I use the term ‘think’ loosely. Really, they are changing how they perceive the bait and this all boils down to how they taste it. Gustation, the sense of taste, in insects, is probably best understood in the old, reliable, Drosophila. The fruit fly’s well documented genome lends itself to many different kinds of mutation experiments, including, as Dr. Frederic Marion-Poll was delighted to explain to the gathering of neuroscientists, zoologists, and other interested parties at his talk, experiments on taste.

Of Marion-Poll’s many examples of experiments performed on the humble fruit fly, one in particular is very relevant. They were interested in seeing whether olfactory receptors (associated with smelling) expressed on taste cells could trigger a ‘taste’ response to an oderant (smelly) stimulus. Interestingly, they observed that not only could the flies taste the ‘smelly’ molecule (using electrophysiological measurements) but also that the behaviour of the flies differed depending on where the olfactory receptor was expressed. When the receptor was expressed in a sweet tasting cell (initiating a sweet response), the fly was attracted to the stimulus but when the receptor was expressed in a bitter tasting cell (initiating a bitter response), the same stimulus triggered an aversive response and repelled the fly.

‘What has this got to do with cockroaches?’ I here you ask. Well, the key finding to take from this experiment was that it didn’t matter what chemical was being tasted. What mattered was where the receptor was being expressed. So, when I heard about populations of cockroaches learning to avoid poisoned bait I immediately thought of the work of Marion-Poll and co.

The bait that has been used for the cockroach traps is glucose, the (usually) universally sweet molecule. On its own and under normal circumstances, cockroaches can’t get enough of glucose. Add a little poison to this delectable treat and the cockroaches were literally killing themselves to get a tasty mealful. Recently, however, populations of cockroaches have been discovered that avoid glucose, whether or not it has been poisoned, in favour of other, usually less desirable foods. More than this, they also show the classic ‘bitter response’ (common to almost every tasting animal) to tasting glucose. This indicates that they are now tasting glucose as a bitter molecule!

‘Wouldn’t it be better if the cockroaches evolved to recognise the poison instead of disregarding all glucose?’ you might ask, and you would be right, except that’s not how evolution works, is it? It is possible that a cockroach could evolve a gene that makes a receptor that detects the poison. A much more likely scenario, however, is that the cockroach accidentally expresses an already existing gene, namely the glucose receptor, in a bitter tasting cell. By doing this, it would react to glucose as if it were a bitter molecule, thereby having an advantage over all the gullible cockroaches in the presence of poison. Is this mechanism feasible, though? Almost certainly! When we consider that olfactory receptors can be functionally expressed in taste cells, it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that a receptor which already exists in a sweet taste cell could ‘hop the fence’ to a bitter taste cell. I think it a much more prudent question to ask: ‘What are we going to do about the impending cockroach apocalypse ’cause we just can’t seem to stop these guys!?’

———————————————————————————–

A Taste of Insanity?

Joe Bliss

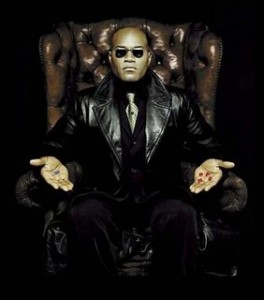

“What is real? How do you define, ‘real’? If you’re talking about what you can feel, what you can smell, what you can taste and see, then real is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain.” – Morpheus, The Matrix, 1999

The 1999 film The Matrix makes us question the reality of our own existence. The main protagonist Neo discovers that his entire world is an electronic simulation, created by sentient machines to occupy his mind while they harvest the energy generated by his metabolism. For the purposes of the rest of this blog, I will make the assumption that the world we find ourselves in is not a simulated reality. However after a research seminar given by Fredric Marion-Poll, I find myself debating the reality around me. Is sugar sweet? What is sweet?

These may sound like the questions of a man on the verge of insanity, but they are interesting issues to raise and are without obvious answers. We can describe a colour by its wavelength and sound by its pitch as these are physical, measurable quantities, but there are no inherent properties of a chemical that define it as bitter or sweet.

Taste is a sensation produced when a chemical reacts with a receptor cell in the taste buds of the tongue. However there are different taste receptor cells, including one for bitter tastes and one for sweet tastes. These cells have an array of unique receptors for a number of different chemicals. If a chemical matches with a receptor on a sweet cell it will stimulate the cell to send a ‘sweet’ signal to the brain.

Marion-Poll suggested that animals have adapted to associate harmful chemicals with ‘bitter’ which stimulates an evasive response. He showed a video of this recognisable ‘bitter response’ in both an insect and in this must-see video of a child being fed grapefruit juice. The research he presented also highlighted that taste has more levels of complexity than just simple recognition. In one experiment, fruit flies were offered a choice of four fructose food sources containing varying levels of strychnine, a highly toxic substance. As expected, flies avoided this toxin as it stimulates a bitter taste receptor. However even when the bitter tasting cell was destroyed in the fly, that strychnine laced food source was still avoided. This suggests that the strychnine also inhibits the sweet tasting cells, further enhancing toxin avoidance. However this was not the case for all the bitter chemicals they tested and the process is not yet fully understood.

As a final intriguing conclusion to the seminar, research was presented which found that some cockroaches in the USA have adapted to avoid glucose baited traps. The sugar bait was made less sweet for these cockroaches which now taste the glucose as bitter, making them avoid the traps. So this begs the fundamental philosophical question; what is the true taste of sugar? As Morpheus might say, it is whatever your mind chooses it to be.

Image: Wikicommons