“Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will not die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistence.” Daniel Burnham

The viva or thesis defence is a daunting obstacle. It’s built up so much that you feel as if your previous three years of work hinge on how you perform for one morning/afternoon. Despite all the reassurances I was offered I was hugely nervous before it. That said, some of the advice I received meant I wasn’t flying blind and could anticipate some of the questions.

It really is a help to have had some of your chapters published. It means two or three other academics have evaluated your ideas and thought them good enough for publication. This is not to say your examiners will ignore these parts, but remember they’re making sure you could perform as an academic and this is strong proof that you could.

Before the day, make a copy of the thesis you submitted and bring it with you to the viva. Have the pages with your figures on it highlighted. These sections are typically big discussion points because they capture the essence of your results. Read over it a couple of days beforehand too, but not the day before, keep that as a buffer to relax.

In terms of structure, the viva panel consists of an external examiner, an internal examiner and the chair. The extern is someone in your field but outside of your university. It is typically stipulated that they cannot have published with you or your supervisor so as to avoid bias. The intern comes from your department and has some knowledge of your field and again has not published with you. The extern takes the lead in asking the questions. The chair is there to make sure everyone keeps a civil tongue in their mouths and the whole event comes to a close after a reasonable time. A typical viva will last three hours.

The aim of the viva is to ensure you are capable of functioning as an academic, I’ve heard it being described as the ‘gateway into the scholarly community’. The expectation is firstly, that the work is mostly your own and secondly, that you have an appreciation of where your thesis fits in with the field at large. This means the questions you’re asked come at two levels, the specific and the general. You are the author so you’re best placed to know the specifics. If you have been helped with some aspect, such as the statistics, make sure you’ve an understanding of why it was done. The general questions are posed to test that you’re widely read in the area. So one question I had was ‘If I could ask God any question about vulture biology what would it be?’The tone of the viva should one of a scholarly discussion. Your examiners are not there to chew you up and spit you out again.

Recognise that your thesis is not the final word on the subject, admit to its shortcomings, and realise it could be improved upon. You can engage in civil debate if there’s a point of difference but don’t get argumentative. You may be asked, in hindsight what would you have done differently?

A good thesis supervisor will know that your work is good enough to get you through a viva with relative ease. Any significant problems will likely have been flagged well in advance. So despite all of your fears coming up to it, you’ll know you’re good enough to walk through those scholarly gates.

#################################################

This post drew on my own experience and the advice offered by the presenters of the BES Webinar ‘Surviving the viva’.

Author: Adam Kane, @P1zPalu, kanead[at]tcd.ie

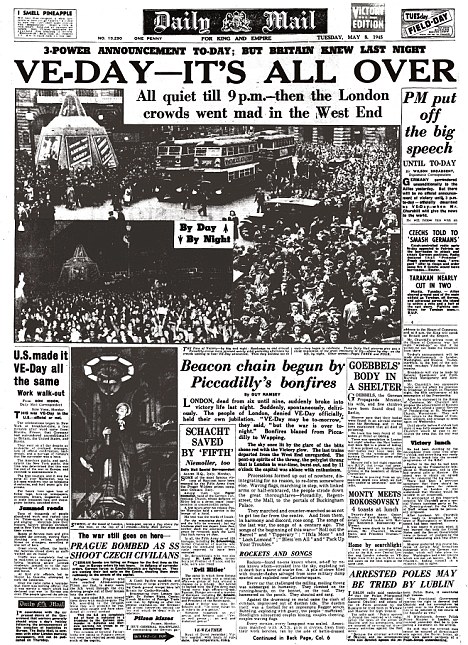

Photo credit: dailymail.co.uk