In 2010 I graduated from the Department of Zoology in Trinity College Dublin. I spent the next year travelling and completing any wildlife related internship or voluntary position I could get my hands on. I soon faced a dilemma; should I follow in the footsteps of my friends in academia and find a PhD or should I keep searching for a conservation job? I really didn’t know if academia was for me but I knew it would be a great advantage if I wanted to make any kind of an impact in the conservation world. I didn’t really want to do a taught Masters, I had enough of exams and I felt I needed to get a bigger more meaningful project under my belt. A Research Masters proved to be exactly what I was looking for. I could sample postgraduate life without having to commit for four years but at the same time I knew I would have enough time to do something of consequence. I shopped around and eventually the idea of doing a Masters in Nottingham started to appeal to me (aided in no small way by the fact my girlfriend had decided to do a Masters there!).

I decided to meet up with my potential supervisors in Nottingham to see what sort of projects they had in mind. They had a plethora of ideas and were determined to find a project that suited my interests and abilities. All their conservation work takes place in the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt and the University of Nottingham has a long established research history with the Sinai. Francis Gilbert (one of my potential supervisors) has fallen in love with the Sinai and has spent over 25 years researching there. His obvious passion and enthusiasm for Sinai was one of the major reasons I eventually chose this Masters. We talked through a variety of ideas but it eventually boiled down to one exciting project. It was proposed that I could carry out the first ever study of an extremely rare endemic butterfly found only around the mountains of the Saint Katherine Protectorate – the Sinai Hairstreak Satyrium jebelia. The butterfly was discovered in 1974 and other than a basic description there was next to nothing known about it. YES PLEASE. Ultimately the chance to carry out some old fashioned, pioneering Zoological research was too juicy to pass up! It also appealed to my dormant inner Lepidopterist (I kept butterfly record books with grid references when I was 11 years old) so that made the decision that little bit easier!

I accepted the Masters and started work in Nottingham in January. We had a vague idea of the flight season of the butterfly and to err on the side of caution (and to spend more time in Egypt!) we booked flights for a whopper four month field season in Egypt. I was insistent that I was there before the butterfly emerged right up to the bitter end. I was given a desk and a laptop and lumped in with other Masters and PhD students, which was great. There was no real differentiation between Masters and PhD students and it gave me a real taste for PhD life. My flight out was not until mid-April so I had considerable amount of time to do some preliminary research. This was a little frustrating because we had no idea what to expect and what I would be doing (a difficulty many field researchers and undergraduate dissertation students know too well). I had to be prepared for any eventuality and the thought occurred to me that this species could be extinct! My priority was to fully map its distribution and get the first ever population estimate for the species, absolutely essential information in wildlife conservation. It would also be impossible not to pick up some other useful information on the way. I researched everything from phylogeny to the best kinds of butterfly nets. The genus this butterfly belongs to is typically found in temperate regions of Europe and North America so why is it found in Egypt much further south than its cousins? The Sinai Peninsula and Egypt were once much cooler and had a much more European climate. Sinai Hairstreaks were probably much more widespread in the past but as the region became warmer the species started to die out. Butterflies are reliant on the distribution of their larval foodplant (what their caterpillars feed on) and it is likely that the Sinai Hairstreaks larval foodplant – Sinai Buckthorn Rhamnus dispermus – could not survive the extreme heat. The only way they could survive was to either move north to cooler climates or to move up in altitude where the environment is much cooler. The Saint Katherine Protectorate boasts the highest mountains in Egypt and has the coolest temperatures, making it a biodiversity hotspot and the last remaining home of the Sinai Hairstreak. I continued to work hard but it did become tedious (I did sneak off more than once to birdwatch in Nottingham…..they have Woodpeckers!) and spent a lot of time reading a PhD thesis by Mike James. He carried out the first ever study of another Sinai endemic butterfly – the Sinai Baton Blue. His thesis was the bible as far as I was concerned and a real inspiration. In one field season he carried out a 97 consecutive day Mark-Release Recapture experiment, legendary!

Eventually the time came where I had to fly to Sinai and I didn’t feel so prepared then! Being a pale Irish person with a ginger beard I was a little nervous about the hot Egyptian sun; a gallon of Factor 50 was packed. I flew to Sharm El-Sheikh airport at the southern tip of Sinai (a popular resort town for sun seekers) and was told a Bedouin from St Katherine was going to pick me up. The word Bedouin is generally used to describe Arabic tribes of a nomadic lifestyle that live throughout North Africa and the Middle East. However, the Bedouin in St Katherine live a more settled lifestyle as they take advantage of the tourism to Mount Sinai (where Moses is said to have read the Ten Commandments) and the Monastery of Saint Katherine. They belong to the Jebelia tribe and the Sinai Hairstreak is named after them – Satyrium jebelia. Eventually my driver showed up and, after a detour or two, (he turned a three hour drive into a six hour drive) we arrived at Fox Camp, lying at the foot of Mount Sinai. I was greeted by some familiar faces because there was a team of different Nottingham researchers there looking at everything from hyenas and wolves to the birds and bees (literally). I was invited to join my fellow researchers and some locals by the fire in the Bedouin tent. This would become a daily routine, talking to my Nottingham friends, the locals and strange tourists over Bedouin tea (ingredients: a small amount of water and black tea with a kilo of sugar).

The first week or so was the acclimatisation period, getting used to the sun and helping some of the other researchers (catching Black-crowned Wheatears with Luke and setting up camera traps for carnivores with Lisa). The first thing I wanted to do was to map all the hostplants, Sinai Buckthorn (a rare and endemic species in its own right) before the butterfly was due to emerge. If I could find the hostplants I could find the butterflies. This proved a little more difficult than I originally thought. I had to rely on local knowledge to find these plants and the Sinai Buckthorn has no real value to the Bedouin so many people don’t know what it is. They often confused it with the similar looking (and more common) Sinai Hawthorn. This lead to being sent on more than one wild goose chase. It is illegal to walk the mountains in the Sinai without taking a local guide with you. This also proved a bit of a nightmare at the start as the first guide I was given was 14 years old and didn’t speak English. I didn’t care too much that he didn’t speak English (it’s his country) but he just didn’t understand what he was supposed to be doing, through no real fault of his own. He would take me to the top of mountain and treated me like a tourist and not a scientist…..so I paid him and sacked him! Eventually I settled on my guide – Suileman Abusada- who spoke English. Unfortunately he didn’t really know anything about the plant but pretended he did. He was so eager to secure my services that he gave me rugs and gifts after our first walk. While he didn’t know much about the hostplant he did know the area very well, was a good cook and was willing to spend days on end in the mountains with me while I looked for the plants. I used a GPS to mark the location of the Buckthorn and started the mapping process. Luckily there was one Bedouin who knew exactly what I was looking for – Nasr Mansour. Nasr exuded coolness (his name means eagle and he has a motorbike) and knew everything there is to know about the flora and fauna of St Katherine. He was already a guide for someone else but I did manage to get him to bring me to some locations and educate Suleiman about what I was looking for.

The next few weeks followed the same pattern, long day trips to Wadis (valleys) around the protectorate looking for this shrub and enjoying the spectacular scenery of the region. The Sinai Buckthorn has a nasty habit of being found in remote areas and along steep rocky slopes. On the 10th of May the project really took off, I was climbing up the side of a particularly tedious hill to check out what I expected were two Sinai Buckthorn. The Buckthorn was usually found in relatively high numbers so one or two trees were hardly anything to write home about. I was wrong; I saw the butterfly for the first time (several weeks before they were due to emerge). It was such a relief to the see the species I had been studying for the past four months for the first time. First off I photographed the butterfly (probably the 3rd known photograph for this species!) and I then proceeded to watch them, trying to get familiar with their behaviour. I knew I had an awkward species on my hands as they were quick and would often disappear out of sight chasing after other species of butterfly or just vanishing altogether. Many arid species (such as the Sinai Baton Blue) rarely move more than a few metres but it was immediately clear that the Sinai Hairstreak was a strong flier. I started to practice catching them which was made all the more awkward because the Sinai Buckthorn is covered in thorns, fixing my net was a weekly occurrence. By that time I was fairly satisfied that I had mapped all the hostplants in the region and I knew that it was time to start to try and estimate the population. I found six large sites containing Sinai Buckthorn and a couple of sites with one or two hostplants. I was confident the butterfly would be present in the larger sites despite that it had only been known to occur in two locations. My assumptions were correct and each of the six sites were teaming with butterflies! Hunting season was open!

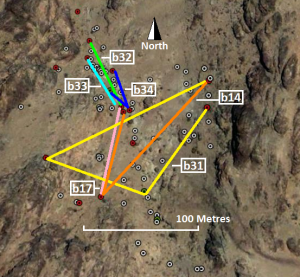

I wanted to have a reasonably good population estimate so I decided to visit each site for five consecutive days to carry out a Mark-Recapture-Release experiment. I would spend eight hours each day (8:00 – 16:00) for five days catching butterflies. This sounds easy but this was (obviously) the hottest part of the day and the trees could be scattered along various different steep slopes. More often than not I was also competing against a dodgy stomach, watch out for the salad! Even the local Bedouin don’t like being out in the heat of the day, Suleiman rarely helped and spent most days sleeping in the shade! He was good craic and cooked so no problems there. The sites were quite remote so I would camp for the five days with Suleiman. We would bring a camel, Abdul, with us to carry our food and water. Each butterfly captured was given an individual mark with a felt-tip pen through the net and released as quickly as possible. The location, behaviour and time were recorded for each capture or subsequent recapture. By looking at the proportion of marked and unmarked individuals we can estimate the population size using Eberhardt’s geometric model. Maps were created using Google Earth showing the movements of captured Sinai Hairstreaks, the distribution of Sinai Buckthorn and the Sinai Hairstreak. I used this method on all the sites except for one (the Wadi Ahmar region) because of the apparent high population of Sinai Hairstreaks there. For this site I visited once marking as many butterflies as I could and then returned five days later to count the proportion of marked and unmarked individuals. The population size was estimated using the Lincoln index. Carrying out population estimates at each site took a good chunk of time and I was afraid the flight season would end while I was still doing it. As I result I worked non-stop during this time which was pretty intense but very exciting. I took notes on everything I could from predators to foodplants while I was catching the butterflies. I also decided to assess the habitat and larval foodplant requirements by recording 11 different features from the height and width to the slope and aspect of every single Sinai Buckthorn, 553 in total. This was much less enjoyable and much more labour intensive than catching butterflies!

It wasn’t long until August came around and the butterflies were completely gone by the time I left. The heat in August was blistering and I was ready to leave after four long months. I returned to Nottingham with a mountain of data and a decent tan. I effectively became a hermit (tan receded quickly) for the next couple of months writing as much as I could without the distraction of exams or lab work. I estimated the total world population of Sinai Hairstreaks to be 1,010 individuals (less than Snow Leopard and Giant Panda). This is very low but unlike many endangered species the Sinai Hairstreak has a naturally small population size. As I mentioned before the Sinai Hairstreak is a relict species that has become isolated on a mountain-top island to avoid the higher temperatures of lowland Egypt. The good news is the Sinai Hairstreak is not under direct threat from people; the foodplant is not used by the locals (they harvest the foodplant of the Sinai Baton Blue) or grazed heavily and the habitat is not being destroyed by human development. I was also keen to establish what population structure the Sinai Hairstreak has. Basing a conservation strategy on the wrong population structure has proved costly in the past. We can do this by looking at the proximity of sites and the dispersal ability of the butterfly. This definitely needs more research but we now know the Sinai Hairstreak is a good flier (I had one beast fly a kilometre in a day). The Sinai Hairstreak may exist as a metapopulation or a panmictic population. It certainly appears to be in a better position than the Sinai Baton Blue. If the Sinai Baton Blue becomes locally extinct in one patch of suitable habitat it is likely that patch will never be recolonized again due to its extremely poor dispersal ability. I also found an individual Sinai Hairstreak that was 25 days old (very good for a butterfly) which is another indication of how robust it can be. The bad news; the only serious threat that the Sinai Hairstreak is under is global warming, if current climate-change predictions are correct the habitat may become unsuitable and there may be no way for the Sinai Hairstreak to survive. They have already reached the top of Egypt’s highest mountain and have literally nowhere left to go to escape the heat.

My work in Sinai was recently published in the journal of Insect Conservation. After I finished my Masters I was invited to attend an IUCN Red List Assessment Workshop on Mediterranean Butterflies in Malaga as an expert in Egyptian butterflies (a very generous statement!) and I was involved directly in the creation of a new regional Red List for Mediterranean butterflies. The information I collected was used to have the Sinai Hairstreak red listed for the first time as Vulnerable. Getting a species on the Red List is a necessary first step in highlighting the conservation concern of a species and I was delighted to get the ball rolling for the Sinai Hairstreak. To sum things up I was thrilled to be able to shed some light on an unstudied species and even more delighted that my research could actually prove useful! It’s hard to believe that it all happened in a single year.

More photos of the wildlife and scenery of the Sinai can be found here.

Author Andrew Power

Photo credit Andrew Power