I sometime come across papers that I missed during their publication time and that shed a new light on my current research (or strengthen the already present light). Today it was Cartmill’s 2012 Evolutionary Anthropology – not open access, apologies…

Cartmill raises an interesting question from an evolutionary point of view: “How long ago did the first [insert your favorite taxa here] live?”. This question is crucial for any macroevolutionary study (or/and for the sake of getting a chance to be published in Nature). If one is studying the “rise of the age of mammals” (just for example of course) the question of the exact timing is crucial to see whether placental mammals evolved after or before the extinction of avian dinosaurs.

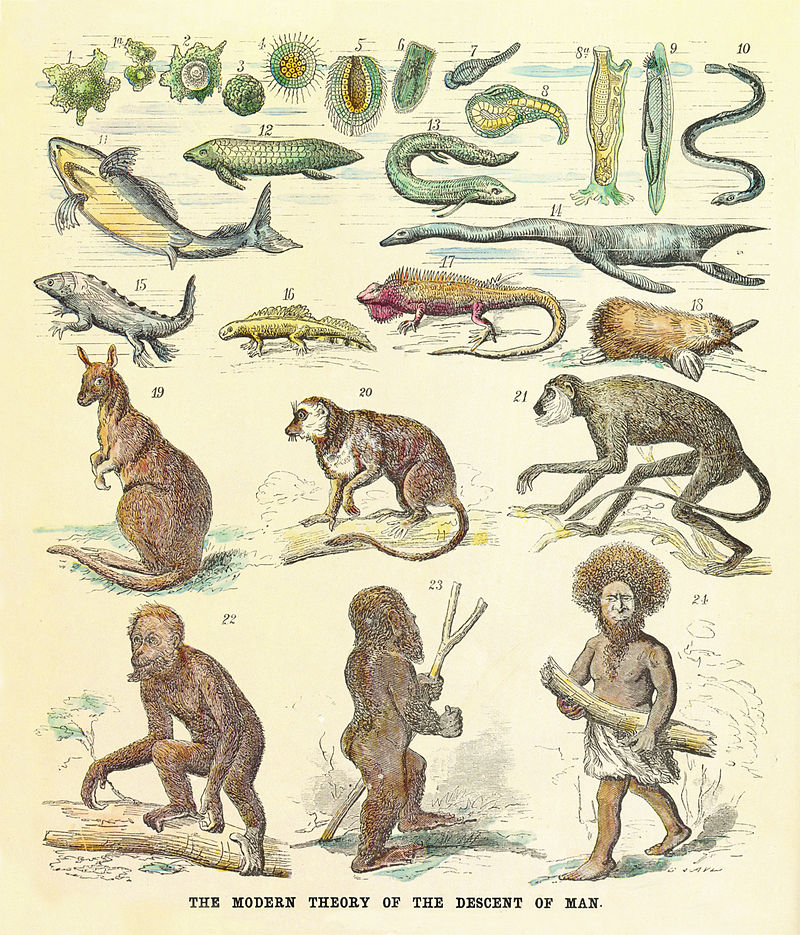

Because Cartmill published in Evolutionary Anthropology let’s replace [insert your favorite taxa here] with humans. He proposes to answer to the question “How long ago did the first humans live?” by looking at the different ways people have addressed it through time. It all starts back with Simpson’s quantum evolution stating that clades share “adaptive shifts” or “adaptive trends”. For example, for humans, that will be bipedalism and an increase in brain size: “Everybody can sort humans out instantly from other sorts of things: […] they share a unique reliance on technology, a capacity for culture, and a gift for gab.”

This is an unfortunate classical view of evolution based on morphological data leading to a series of morphological discontinuities – the adaptive shifts (“human origins, primate origins, mammal origins, amniote origins, and so on” – I already discussed this gradualistic view about tetrapod origins). Cartmill uses a pertinent quote from Simpson to comment this trend: “Is this not, in fact, simply a recrudescence of the old naïve conception of a scala naturae[?]”. However, this raises a cladistic problem. Assuming we have the data on the oldest human. What defines his or her humanness? “Humanness [whatever that means] is not a coherent package. We have known since the 1960s that our terrestrial bipedality evolved more than two million years before the onset of what was long held to be the fundamental human characteristic, that is the great development of the brain.’’

Cartmill’s point is that, morphologically, there is no adaptive shift or trend that can define any group. Morphological evolution acts more like a succession of slow and discrete incremental changes rather than the Simpsonian quantum model: “there is only a long, geologically slow cascade of accumulating small apomorphies” and adaptive trends or shifts within clades “are fantasies, born ultimately of our wish to see ourselves as more decisively set off from other animals than we actually are.”

Will I have to rethink my current project looking at mammals morphological evolution? Well by using molecular data as well as morphological data we can accurately trace back the small incremental changes (the DNA mutations) as well as the actual changes in morphology through time. My PhD is not just a series of failures after all!

Author

Thomas Guillerme: guillert[at]

Photo credit

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_chain_of_being#/media/File:Human_pidegree.jpg