Invasive freshwater fish (Leuciscus leuciscus) acts as a sink for a parasite of native brown trout Salmo trutta (2020) Tierney et al. Biological Invasions. Read it here.

Adapted from blog published at Ecology for the Masses

Alien invasions and parasite infection

From house cats to cane toads, invasive species are one of the biggest threats to native plants and wildlife, second only to habitat destruction. An invasive species is a living organism that is a) introduced by humans from its native range to an area it doesn’t naturally occur, b) spreads and forms new populations and c) causes some kind of damage to the native ecosystem, economy or human health. Current lockdown conditions notwithstanding, introductions of invasive species have become increasingly common in our globalised world with easier travel and trade between countries. The spread of invasive species creates new ecological interactions between native and invasive species that can impact how our native ecosystems function, including disease dynamics. If the development and transmission of native parasites is different in invasive hosts compared to their usual native hosts, the parasite dynamics of the whole system can be altered.

The power of parasites

Parasites make up a huge but desperately understudied component of biodiversity. An estimated half of all living organisms are parasites and almost all free-living organisms are infected with parasites. Parasites are admittedly hard to study; they are hidden on or in other organisms and this means they have been chronically underestimated in biodiversity studies. But when we do add them in, it literally turns our perception of food webs on its head. When parasitic interactions are included in food webs, the number of parasites flips the classic trophic pyramid flips upside-down and the number of trophic connections quadruples. Parasites are powerful players in ecological systems – they regulate food networks, control the abundance host populations and act as bio-accumulators for toxins in the environment – so it is important to study them when trying to understand the impacts of invasion on native ecosystems.

Our study system: invasive dace and native brown trout

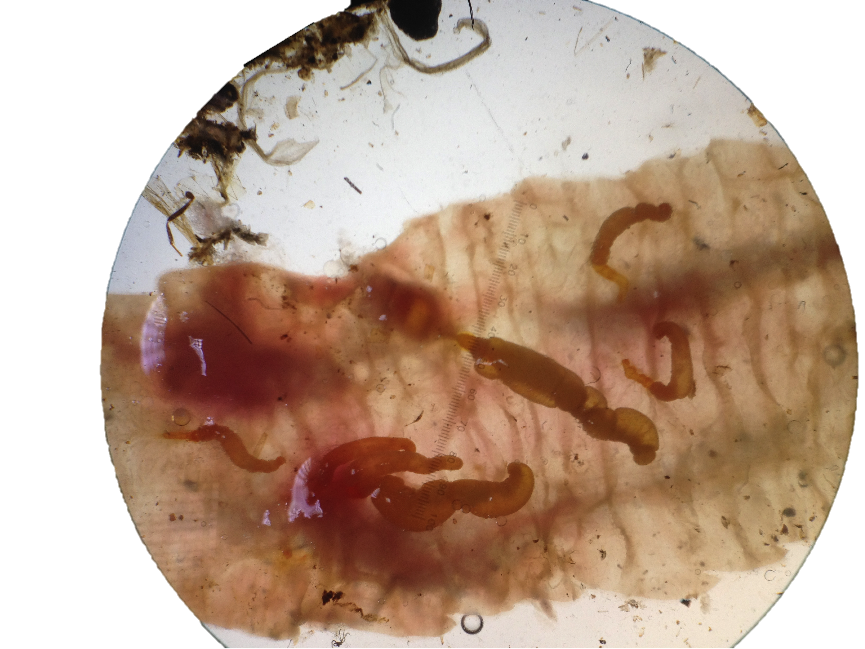

We set out to study differences in parasite infection between a native and invasive host using two invaded river systems in Ireland as a kind of natural experiment. The Munster Blackwater has been invaded by the freshwater fish dace for over 130 years while the Upper River Barrow has been invaded for less than five years. We studied infection of the widespread acanthocephalan parasite (AKA thorny-headed worm) Pomphorhynchus tereticollis in dace in these long-established and recent invasions. We compared invasive dace to the usual native host, brown trout, which we sampled from the same sites. We wanted to know about differences in host competency: the capacity of a host to allow the growth and development of a parasite. Using the relative proportions of adult and immature subadult parasites and the development of eggs inside the female parasites, we were able to assess whether invasive dace are suitable and competent hosts for the native parasite P. tereticollis.

Incompetent invaders

We found that invasive dace were generally less infected than native brown trout, especially at the recently-invaded sites. In brown trout, almost all the parasites were adults (as we would expect from a preferred host) but in dace, 88% of the P. tereticollis worms were immature subadults. These subadult forms tend to be found in unsuitable host species; they represent a bit of a developmental dead end for the parasite and probably don’t contribute to ongoing parasite transmission. Parasites infecting invasive dace were also smaller than those from brown trout. From looking at the parasite eggs, we discovered that none of the female parasites in dace reached sexual maturity, meaning that dace were not transmitting infectious parasite stages. The combination of low infection, lots of subadults, small parasites and no mature females in dace all point to the conclusion that dace are incompetent hosts for the native parasite P. tereticollis.

Dilution of disease

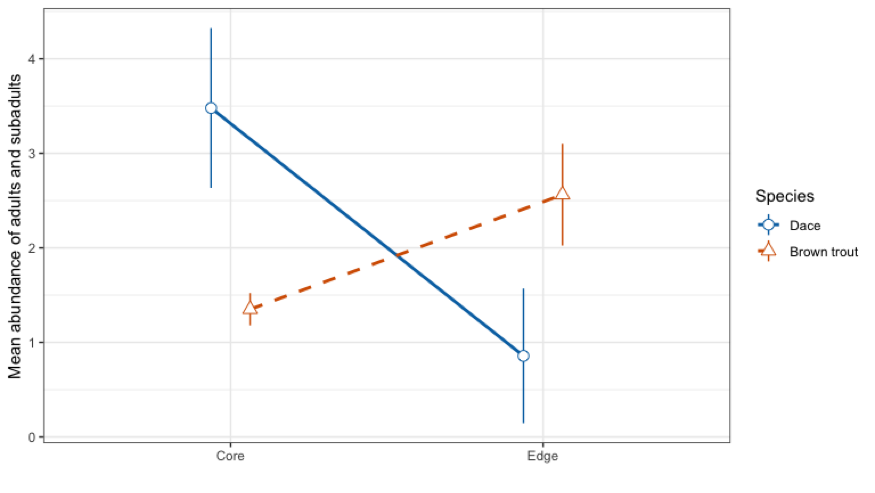

We discovered that invasive dace are incompetent hosts but does this affect disease dynamics? If dace are taking up infectious stages but not contributing to the cycle of infection, they could act as sinks for infection and dilute infection in native hosts. We homed in on our native fish species and compared infection in brown trout between the long-invaded sites where infection in dace was high and the recently invaded sites where infection in dace is low. We found that native brown trout in the long-invaded sites had a lower abundance of parasites than their counterparts in the recently invaded sites. This is evidence that the presence of invasive dace has diluted native infection over time.

Long-term impacts of invaders

Invasive dace in Ireland become infected with the native P. tereticollis parasites but do not transmit them, resulting in reduced infection in the co-occurring native host, brown trout. However, this is only apparent at the long-invaded sites where dace have been present for over a century. So, while the presence of invasive species can certainly affect disease dynamics, the impact may not be apparent until long after the invader is established. We can’t yet be certain whether this dilution of parasite infection is good or bad news for native brown trout since the role of parasites in ecosystems can be complex and multi-faceted. However, our study does provide some much needed real-world evidence of altered parasite dynamics by an invasive species.