Indonesia is a constellation of islands, big and small and many-shaped, born out of volcanism or coral build-up or sheared from the ground of continents, each its own world. The complex geography of this region begat an equally complex biogeography, with evolution working enthusiastically to populate it, and the staggering biodiversity that resulted will surely occupy biologists for centuries to come (as long as it lasts that long). Every nook and cranny is filled with fascinating plants and animals, and our research group recently published a paper on the avian contents of a couple of those nooks and crannies. This post follows one by Darren on the fieldwork stories behind that paper, and the expeditions to remote Muna and Wawonii islands.

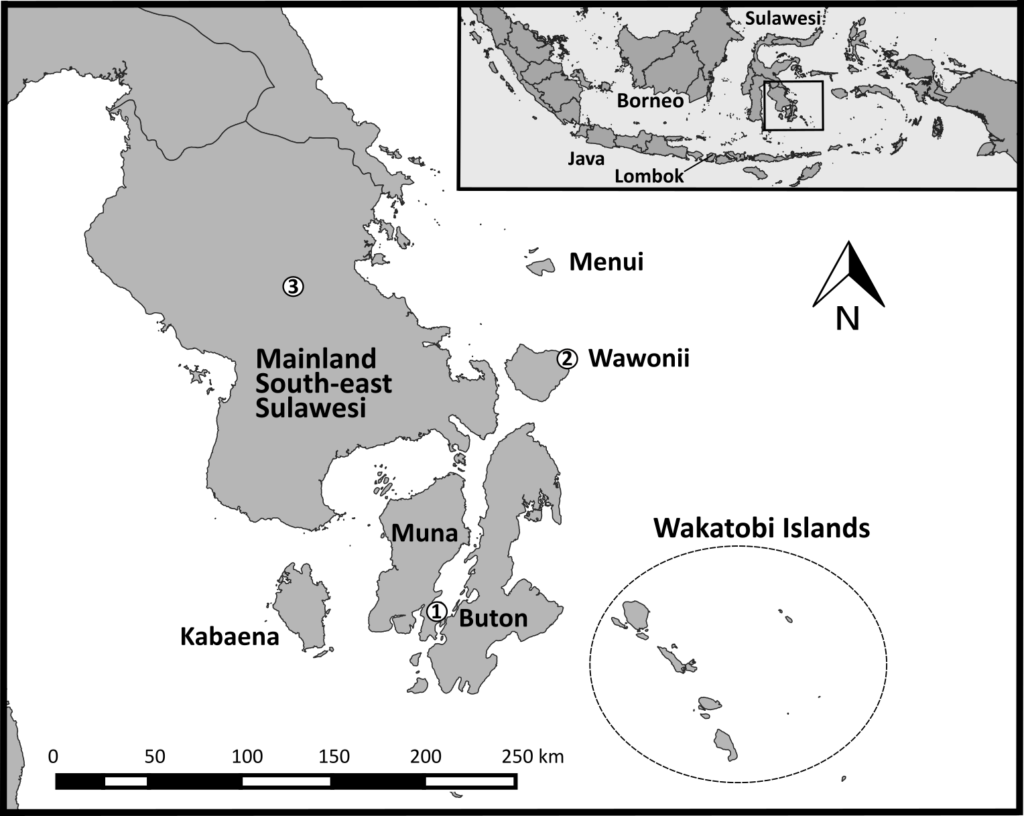

Ours is the first study ever on Wawonii’s birds, and the first from Muna since the 1950s. To give an idea of how thoroughly the ornithological literature overlooked Wawonii, two longstanding authoritative texts on the region’s birds (those of White and Bruce and Coates and Bishop) ignore the island entirely. It isn’t even labelled on their maps: on our research group’s copy of Coates & Bishop, the name “Wowoni” has been carefully added in ballpoint pen. This is itself an outdated spelling of the island’s name: Wawonii is now favoured in both Indonesian and English, the name of the island’s majority ethnic group and their unique language. The many scattered islands of Indonesia have developed incredible cultural diversity, mirroring that of the flora and fauna and shaped by the selfsame processes of isolation and connection. Over 700 languages are spoken in Indonesia, many of them now threatened. Muna and Wawonii, for example, are only around 60km from each other at their closest points, but their native languages come from two different language groups. There are twenty languages native to Southeast Sulawesi alone, divided between the Bungu-Tolaki group (including the Wawonii language) and the Muna-Buton group.

Just as the islands have been called by multiple names at multiple points, so too have their birds. This complicates research like ours, as all records have to be checked against previous papers on the island, which in turn must be cross-referenced against current and past taxonomy. This taxonomy can be bewildering in its own right, as you might expect from such a biodiverse and scientifically neglected region. It fell to me to sort it out for the recent paper. As one example, Darren and team identified a cuckoo on Muna which is listed in the Coates and Bishop guide as the Rusty-Breasted Cuckoo Cacomantis sepulcralis, but more recent taxonomists have abolished this species and absorbed it as a subspecies of the Brush Cuckoo Cacomantis variolosus. As a further complication, the Sulawesi population has been designated as a different subspecies, C. v. virescens (rather than the rusty-breasted C. v. sepulcralis). Similarly, our Pale-blue Monarch Hypothymis puella was until recently considered to be an unhelpfully blue-naped population of the Black-naped Monarch Hypothymis azurea. As for why the “pale blue” common name has been mismatched from the azurea scientific name, I can think of no reason but spite.

The lack of scientific knowledge of the ecosystems of these islands is even more concerning in light of their grave and imminent threats. Much of the primary rainforest of South-east Sulawesi has already been lost to agriculture, and now large-scale nickel mining is poised to ravage not only the natural ecosystems but also the local communities and their traditional way of life. Such developments promise great wealth to a small number of people, based mostly in China and in Indonesia’s urban centres. Tensions between mining and the fishing and farming of Wawonii locals came to a head last year with protests in the mainland city of Kendari, followed by a lethal police response. On neighbouring Kabaena island, covered in a previous EcoEvo post, Tangkeno village has organised a resistance to a mine there that would have butted right up against people’s homes and cut through their farms. As part of this, Tangkeno was designated as a Tourism Village and a festival plaza was built where the mine had been planned, indicating the role that tourism can play as an alternative to destructive industry in tropical regions. Hopefully that role does not become too tenuous in our new coronavirus world.

To find out more read our full Forktail article: ‘The avifauna of Muna and Wawonii Islands’[efn_note]O’Connell DP, Ó Marcaigh F, O’Neill A, Griffen R, Karya A, Analuddin K, Kelly DJ and Marples NM (2019) The avifauna of Muna and Wawonii Islands, with additional records from mainland South-east Sulawesi, Indonesia. Forktail, 35: 50–56.[/efn_note].

Acknowledgements

Thanks to TCD, Halu Oleo University and Operation

Wallacea for facilitating, planning and providing logistical support for this

research. A big thanks to Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi

(RISTEKDIKTI) for providing the necessary permits and approvals for this study

(159/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017 and 160/SIP/FRP/E5/Fit.KIVII/2017). Huge

thanks to the legend that is Sulaiman La Ode for achieving the killer combo of

being an adept logistics operator and translator, and a top class field worker.