Sexual conflict between males and females is well documented in the animal kingdom. Often, the best strategy for one sex is not the optimum for the other. In mammalian species, lactation of new mothers suppresses ovulation. Therefore, males gain a reproductive advantage (earlier mating opportunity) by forcing early mother-offspring separation. On the other hand, females benefit from prolonging care for their current young, so it has been hypothesized that they adopt counter-tactics to avoid premature separation from their offspring.

The paper “Proximity to humans is associated with longer maternal care in brown bears” by Van de Walle et al. (2019) provides evidence for a new tactic observed in Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos). They tested whether the peculiar behaviour of certain female bears inhabiting areas closer to humans during mating season (i.e. when mother-offspring separation typically occurs), was a tactic used by the females to spatially segregate from adult males and thus allow for longer maternal care.

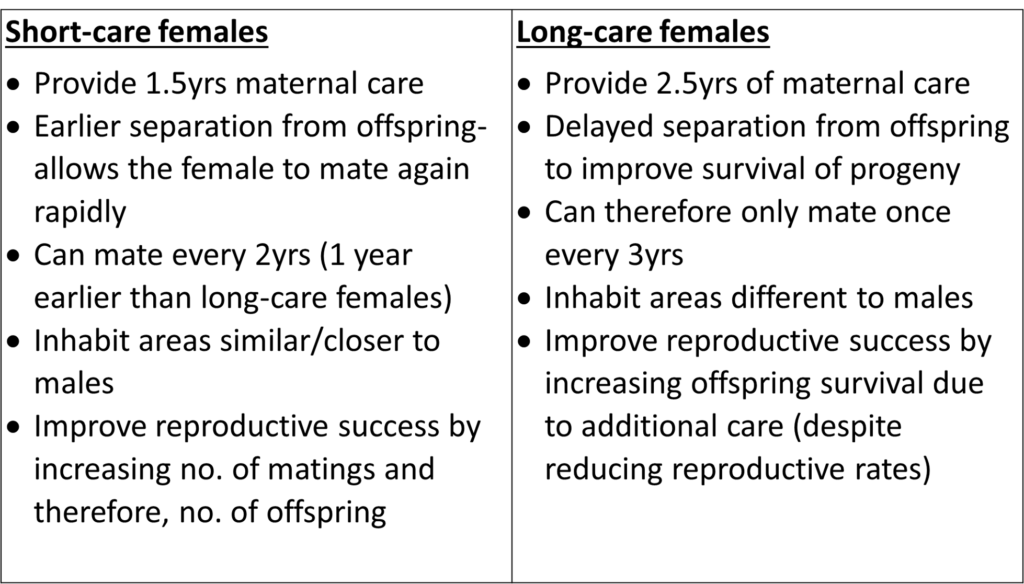

As part of a long-term monitoring study conducted in Sweden from 2004-2016, brown bears were fitted with GPS collars that allowed tracking of their positions every hour. Using these, data were collected between the period of den emergence and family break-up to compare habitat selection between short-care females, long-care females, and males. Short- and long-care are two alternative strategies brown bears employ when rearing young and the differences between the strategies are detailed below. Broadly speaking, long-care females invest more time and energy in their young but as a result have fewer offspring than short-care females.

Both maternal strategies have similar fitness outputs for females (i.e. on average they short- and long-care females produce the same number of young, or, at least, the same number that reach adulthood), so both are maintained in the population. However, the reproductive success of male bears is measured solely by how many successful matings they can achieve. Since extended parental care reduces female availability for reproduction, males bears induce oestrus (fertility) in females, either by infanticide (male kills unrelated offspring and mates with victimized female), inducing abortion or premature weaning of offspring, in an attempt to increase their reproductive success. Indeed, many documented cases of family break-ups have had males observed in the vicinity, and aggressive male bears are responsible for up to 16% of annual mortality of yearlings in Sweden.

To combat this, female brown bears with yearling cubs use a counter-strategy – they alter their habitat and daybed selection patterns to avoid aggressive males during the mating season (spring to early summer). This study found that, during the mating season, short-care females chose similar habitats to males (so they could obtain a mating to give birth to a new litter as soon as possible). On the other hand, long-care females chose to stay in habitats near humans, which males actively avoided.

Hunting is the primary cause of mortality in brown bears in Sweden, so bears tend to perceive humans as a threat and avoid them. Consequently, this propensity of females with cubs to live nearer to humans compared to solitary females and adult males can be interpreted as a safety tactic. If using human habitations improves cub survival, then brown bear mothers are happy to take the risk of living close to humans to invest more care in their young.

Interestingly, females timed their association with human habitats very carefully. When cubs are young, they preferred to stay in areas near humans, but when the cubs were in their second year, females reverted to choosing habitats away from humans. Essentially, when the young were getting old enough to look after themselves (maternal care doesn’t exceed 2.5 years in this population), females started sharing habitats with males again in search of a new mate.

This study provides a fascinating contribution to our limited understanding on the factors governing maternal care duration in the wild. The results are especially important as we know remarkably little about how sexual conflict and parental care duration interact. It is also a poignant example of how animals evolve to cope with and even use human-dominated landscapes, and how human activities can unknowingly shape even the most fundamental animal behaviours.

Reference:

VAN DE WALLE, J., LECLERC, M., STEYAERT, S. M. J. G., ZEDROSSER, A., SWENSON, J. E. & PELLETIER, F. 2019. Proximity to humans is associated with longer maternal care in brown bears.