- A Beginner’s Guide to Dietary Conservatism - 08/03/2021

Talking about your research interests can be stressful. After all, you’ve spent ages poring through the literature, devising experiments, developing a thesis, justifying your ideas for grants and in publications – trying to condense that into something appropriate for casual conversation (often with a well-meaning relative asking “what are you studying?”, shortly followed by “oh, what’s that?”) is a dangerous rabbit hole. It’s even more perilous when your research interest is something that’s virtually unknown even among other researchers in the field. Trying to explain something that niche to an audience can very quickly make you look quite mad. My research is on dietary conservatism. Hands up who’s heard of dietary conservatism?

I don’t see many hands raised (although this is a blog post so it’d be weird if I did) and I imagine the only hands in the air would belong to people who saw me trying to explain dietary conservatism in far too much detail in a 5-minute presentation last year.

So, to save my future conversations from devolving into me rambling about why I have to watch fish eat for hours at a time and why this is important, I have decided to write this post as the definitive, beginner’s guide to dietary conservatism to which I can refer people should they ask me in future “what are you studying?”. (Hi grandma!)

What is dietary conservatism?

Think of dietary conservatism like fussy eating… in animals.

We’re all (I assume) familiar with fussy eating in children, but it might surprise you to know that animals can be fussy eaters, too. Animals have to be very careful about what they choose to eat, especially when it comes to something they haven’t encountered before. Novel prey might be toxic or dangerous to handle, or it might just be difficult to catch and not worth the effort. To cope with all the hassle involved in novel foods, some animals simply refuse to eat them. This behaviour is dietary conservatism.

A more nuanced definition of dietary conservatism describes it as a long-lasting avoidance response, and refusal to include a new item in the diet, despite extensive experience of it. This is a bit of a mouthful, and, like any rigorous definition, doesn’t really convey what the behaviour involves or how weird it is in a tangible sense. For that, we need to see dietary conservatism in action, so roll film!

It’s kind of hard to see in this video (hopefully it played correctly in whatever format you’re reading this), but in the tray are 6 pieces of food arranged in a circle – 3 blue and 3 green (the camera had a really hard time picking up the colours, so you’ll just have to believe me). The chick (called TopLeft) was trained with blue food since he hatched and hadn’t encountered the green food until this point. The only difference between the foods is the colour, but as you saw in the video, TopLeft just wasn’t interested! After eating the three pieces of blue food, he pecked inquisitively at a piece of novel, green food, but rejected it, and spent the rest of the 3- minute test walking around the arena, ignoring it (the third green food gets kicked behind the lip of the tray, but it’s still there!). Not only did TopLeft reject the novel food in the video above, he did the exact same thing twice more, refusing to eat any novel food for 9 minutes in total! Compare that to the chick in the next video, who happily gobbles up the novel food without breaking stride.

Based on the definition above, TopLeft definitely shows dietary conservatism – long-lasting avoidance and refusal to incorporate the novel food into his diet (9 minutes is long relative to the chicks that did eat the novel food!) despite experience. Since TopLeft exhibits dietary conservatism, we describe him as dietary conservative, or DC for short. Meanwhile, our other chick (TopRightBottomLeft) shows no dietary conservatism and we describe him as an adventurous consumer, or AC. This difference between being AC or DC seems to be genetically controlled, too, rather than something an animal learns.

In the lab, it’s not practical to test dietary conservatism over very long timescales, so short tests for dietary conservatism must be used. However, you’d be very mistaken to believe that DC individuals only reject novel foods for a few minutes at most. Studies on wild birds found that some individuals refused to eat novel-coloured foods for weeks or months of exposures, and in one extreme case a particular blackbird refused to eat novel-coloured foods for over two and a half years of testing! Given that blackbirds live on average around three years, that’s a big part of a bird’s life affected by dietary conservatism.

It’s not just birds that show dietary conservatism, either. As well as the ten or so species of bird that have been studied for the behaviour (including Japanese quail, blue tits, and zebra finches, to name a few more), dietary conservatism has been seen in newts and frogs, and four species of fish! In fact, every vertebrate species so far tested has been found to have both AC and DC individuals, and this is where the behaviour starts to get very weird and very interesting.

Why is dietary conservatism!?

Dietary conservatism seems to be found across all vertebrate taxa and DC individuals in every population – it’s everywhere! But why it exists is still a mystery. Why do some individuals refuse to eat novel foods, even when the only difference is something as trivial as colour? DC individuals are, essentially, giving up a (possibly) good meal for no apparent reason. (In the case of TopLeft and other animals tested, it absolutely is giving up a perfectly good meal because the only difference between the familiar and novel foods was the colour!) How could this foraging strategy evolve and why does it persist? And if there’s some hidden advantage to dietary conservatism, why do AC individuals exist, and how do the two different strategies coexist? This remains the crux of the dietary conservatism enigma, and research has only scratched the surface of the answers.

Earlier, I suggested several reasons why an animal might avoid the hassle of dealing with a novel food – it might be toxic, hard to handle, etc. – but these explanations have yet to be put to the test. Moreover, animals have some plasticity in how they express dietary conservatism – DC individuals can (and, logically, must be able to) learn to accept novel foods eventually and AC individuals can learn to reject unprofitable foods, so why don’t all animals just behave as the situation demands*?

The answer is… we don’t really know. We still don’t understand why a behaviour that is so common in the animal kingdom exists. That, alone, makes studying it well worthwhile, but understanding dietary conservatism has a lot of practical applications. How do you get animals in captivity to accept new foods if they’re DC? How do you maximise the welfare (and weight gain) of animals in husbandry? And if you’re reintroducing or relocating animals in the wild, how do you maximise their survival in a new environment with new types of food?

That concludes this beginner’s guide to dietary conservatism and why it’s such a fascinating subject, and why I spend almost all my time thinking about it. As a final, parting thought on why dietary conservatism is so interesting, consider this – dietary conservatism may also influence human eating habits. We are, after all, vertebrates, and if dietary conservatism has been seen in every vertebrates so far studied for it, it’s not hard to imagine that it also exists in us. In fact, just like dietary conservatism has a genetic component, “fussy eating” in humans does, too!

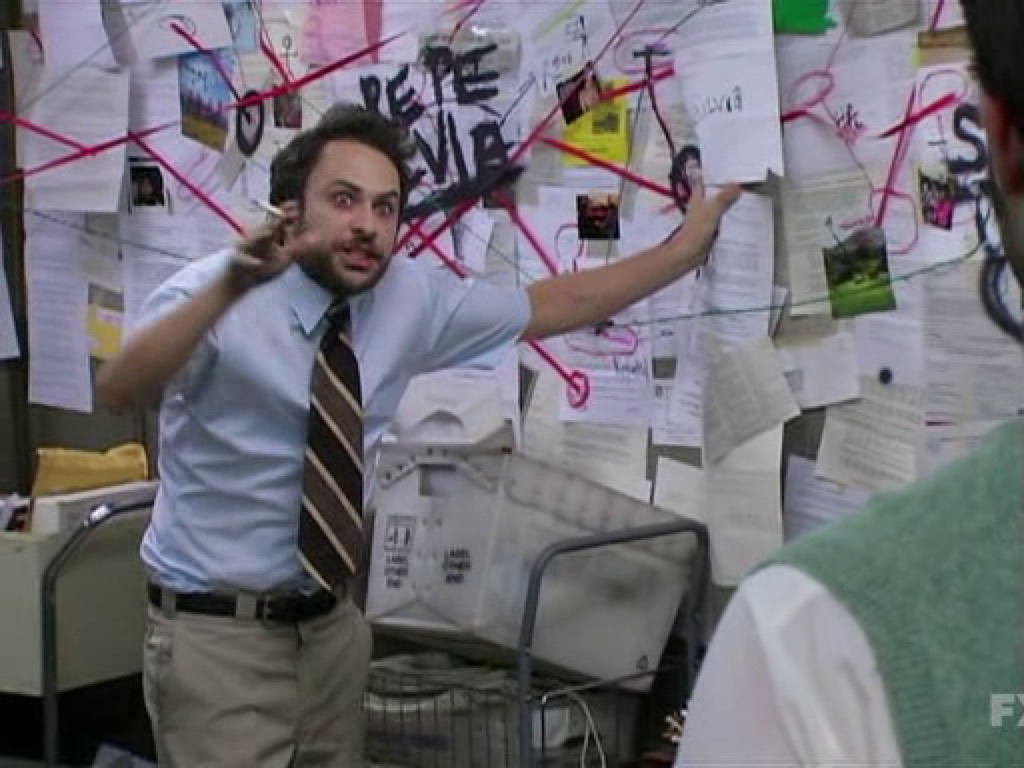

*There’s a whole other blog post to be written about how complicated the mechanism of dietary conservatism is when you start to consider learning, but I’m already starting to feel like Charlie so I’ll stick to the “beginner’s guide” theme and avoid that rabbit hole… for now.