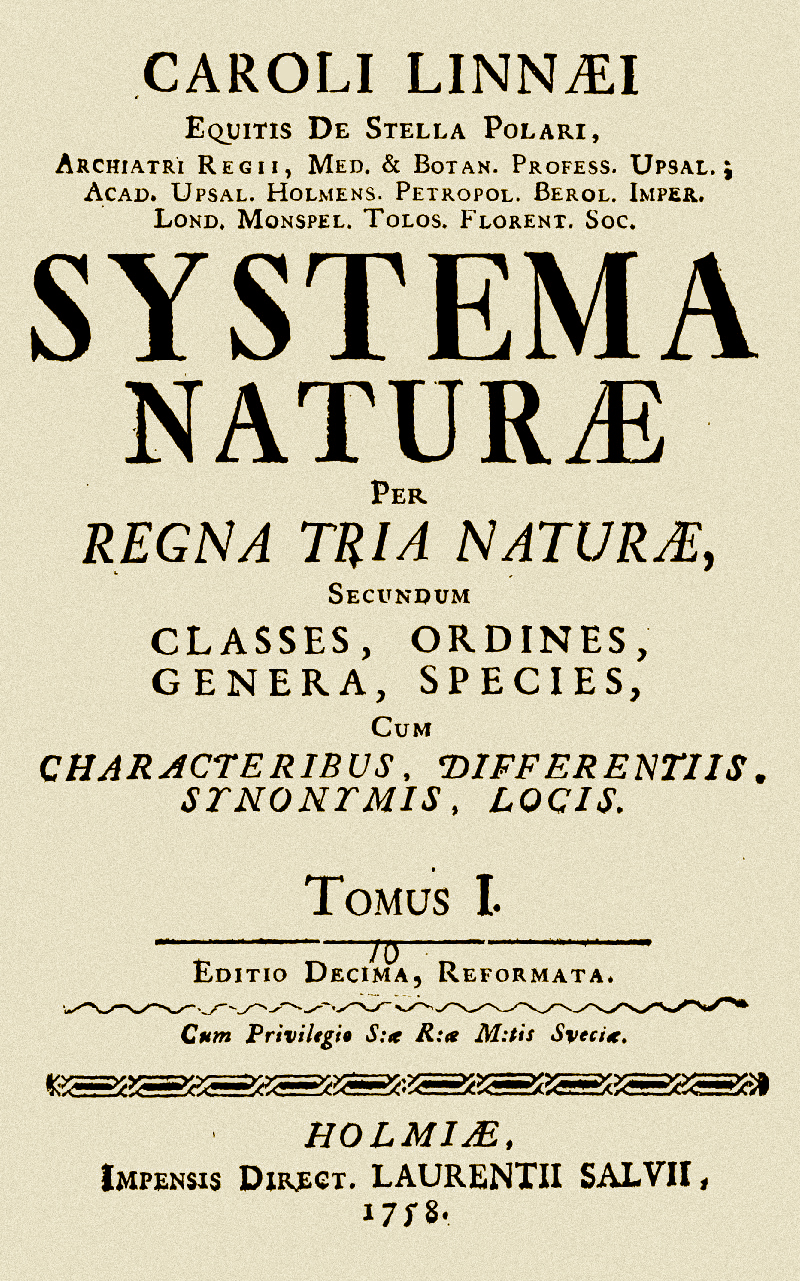

Carl Linnaeus has a lot to answer for. As a young medical student he became obsessed with botany, then a necessity as most medicines were derived from plants. At the time the naming of plants was a rather haphazard affair, some names were given to multiple plants, others could be many words long. It all made for great confusion and difficulty disseminating information. In an attempt to manage the situation, in 1735 he published the first edition of his masterpiece of classification, the Systema Naturae. Most people remember this book as being the first time that plants were classified according to the now familiar Kingdom, Class, Order, Genus and Species (family was a later addition). What they sometimes forget is that it was also the first time that plants, and later animals, were given a standardised binomial designation. This was a revolutionary idea and quickly came to dominate the literature and is still in place almost 300 years later. Continue reading “A Rose by Any Other Name”

Hopsolete Trees

One of the most unusual benefits of being in Ireland from a Southern French PhD student’s perspective is not so much the rain and the pronounced taste for culinary oddities (some weird, some excellent) but the awesome trend towards a new age of craft beers (and I’m not mentioning the pillar of Irish pub culture). Looking at the increasing beer richness available in any decent pub/off-licence, I was inspired to combine two of my passions: beer-related stuff and phylogeny-related stuff. Despite an honourable attempt by J.L. Brown, I would like to discuss the three reasons why it’s imphopsible to build a true beer phylogeny. Admittedly one of the main reasons for this impossibility is the side effect of drinking any sugar rich (at least originally) drink that has been infected by Saccharomyces cerevisiae… But there are also three more theoretical reasons. Continue reading “Hopsolete Trees”

And to the victor the spoiled

Sometimes something is so obvious we forget to wonder why; why do our fingers resemble prunes when we over-extend our bath time, why don’t humans have a penis bone (stop sniggering in the back please and have a look at these fascinating links) and why do prunes rot when the very purpose of fruit is to be eaten?

I’m guessing that for the last one you might say that fruit rots because all the bacteria have decided that you have overlooked the healthy option for the biscuits one too many times and so have decided to chow down. However there might be more to that horrid smelling milk then a simple bacterial get together according to a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. It turns out that that this might actually be a tactic by our microbial co-occupants to put us off and so leave the micro-revellers to savour their lactose lunch while we suffer taking our tea and coffee black. Continue reading “And to the victor the spoiled”

Kapapo, Kereru and Kaka, Oh My!

Before I moved to New Zealand birds were, well, birds. They were nice to see but I didn’t pay them much attention. But New Zealand is a bird paradise and as a biology student (I studied for my undergraduate degree at the University of Auckland) birds were the go-to exemplar of many biological concepts. With understanding often comes interest and I found myself increasingly interested in our avian friends, an interest which has stayed with me to this day. Continue reading “Kapapo, Kereru and Kaka, Oh My!”

Presentation tips: how to create and deliver an effective talk

Off the back of our recent Postgraduate Symposium, I thought it would be useful to summarise some of the advice and criticism we received afterwards. These points are a mix of the feedback from our invited speakers, academic staff and fellow postgraduate students, as well as some of my own observations and preferences. While the majority of the information below is common knowledge and most people do their best to give a good talk, the reality is that there is no such thing as a perfect talk and there will always be room for improvement; that’s fine! Just do your best and afterwards take note of what areas you would like to improve.

1) Remember: slides are an aid to your talk, they are not the focus. Your voice should be the primary focus of the audience; the accompanying slides are to help you explain more complicated ideas and results, introduce a study system or area and generally keep your audience interested (hence the inclusion of many an interesting/pretty/grotesque picture). Therefore, in general, you do not need large sections of text on your slides. As much as you may think the text is necessary, it most likely isn’t so get rid of it! This removes any temptation to read off the slides and helps keep your audience focussed on you. Furthermore, you are more likely to give a better talk with a more natural flow if you stick to this. The most informative and enjoyable talks I have seen typically contain slides with almost no text, primarily using figures, photos, cartoons etc. Also, don’t go for overkill and try to say too much. Present a concise, clear and fluid story for your audience to follow, leaving out any gritty methodological and statistical details that are not central to your research.

2) Talk to the audience – all of it – and never to your slides. This means that you always face your audience, regularly changing the direction of your gaze, speaking loudly, slowly and clearly, therefore engaging as much of the audience as possible. Furthermore, when you are presenting to an international audience, remember that English (or whatever language you are speaking) may not be the first language of many attendees. This is when it is even more important to make an effort to speak loudly, clearly and slowly (and avoid using any slang).

3) Enjoy yourself! Do your best to smile, relax and be enthusiastic about your research. Unlike a typical manuscript, a presentation allows you to inject some passion for your work. If you are not engaged or enthused, how do you expect your audience to be?

4) Always remember to state the general importance of your research and what areas it applies to. Make your research and topic as relevant to as many people as possible (within sensible limits, of course). This is sadly overlooked by many postgraduate students and can be frustrating to watch. You can do this (i) at the beginning by starting with a broad introduction (this does not equate to five slides of background information, rather it could simply be a few sentences, just to provide your audience with a context) and (ii) at the very end, discussing the implications of your results to your field as a whole, addressing the scope of the symposium/conference/session if particularly appropriate.

5) If a particular aspect of your work is complex and difficult to explain, do your best to deconstruct it with the relevant figures and always repeat the main point/finding before proceeding.

6) Always handle questions in a polite, interested and engaging way. Be open, not defensive. A good tip is to repeat each question for the audience so that they all hear it. While this keeps all of the audience clued in, it also gives you time to formulate a response in your head. When you respond, remember to address all of the audience, not only the ‘questioner’, and always mention that you’re happy to discuss things further afterwards (I’d go as far as encouraging people to come chat to me afterwards, even if it is just to grill me; a grilling is always welcome as a postgrad!).

7) Dress for the occasion. Be comfortable but also mindful of why you are giving a talk and who you are giving it to.

8) If you are using a laser-pointer, avoid waving it around excessively on the screen. Use it sparingly, only when a particular detail needs highlighting.

9) Always check the compatibility of your files, allowing time to make amendments if needed, save in multiple formats and have back-ups, whether on another storage device or in your email inbox.

10) Learn from other presentations what aspects you particularly like and dislike. For example, I prefer when acknowledgements come at the start of start of a talk as this allows the speaker to finish with a focussed, ‘take-home’ message of the research. Also, you don’t need to read out every name in your acknowledgements; people will always do it themselves so just go for the major ones.

11) Practice your talk multiple times aloud (how it sounds inside your head does not equate to how it actually comes out).

12) Finally, don’t panic; be confident and do your best.

Author: Seán Kelly, kellys17[at]tcd.ie, @seankelly999

Image Source: phdcomics.com

Echolocating Tenrecs

I’m going to Madagascar tomorrow.

I have all the essentials; insect repellent, tent, flat pack wooden box, bat detector, three metres of blackout curtain material… Not the most usual of packing lists admittedly but all necessary items for the trip ahead.

I’m going to study tenrecs; cute mammals which are the subject of my PhD. I’m interested in convergent evolution between tenrecs and other small mammals. So far I’ve been focusing on morphological convergence – work which has involved trips to beautiful museums and taming the dark arts of morphometrics. The primary aim of my research is to assess the evidence for morphological and ecological convergences among tenrecs and the mammals they resemble. Technically I could complete these aspects of the project without ever seeing or dealing with the live animals. But where’s the fun in that?! I’m also interested in behavioural convergences among tenrecs and other mammals, particularly reports of the abilities of some tenrecs to echolocate.

Some shrews produce echolocation calls by clicking their tongues. More recent work indicates that shrews seem to use these clicking calls primarily for navigation within their habitat rather than communication. Intriguingly, there is evidence that at least three species of tenrec; the lesser hedgehog tenrec, lowland streaked tenrec and Dobson’s shrew tenrec, can also echolocate. The animals seem to use their tongue clicks for navigation. The stridulation sounds produced by specialised spines in lowland streaked tenrecs and juvenile tail-less tenrecs have also been linked to having an echolocatory function but immobilising the spines doesn’t seem to affect the animals’ abilities to navigate by sound.

These early experiments are tantalising evidence of intriguing behavioural convergences among shrews and tenrecs. However, limitations of 1960’s acoustic technology and the ever so slight changes in standards of experimental practice (blinding animals with cement doesn’t go down so well with modern ethics boards!) mean that the study of echolocation in tenrecs is ripe for further exploration.

Hence my unusual packing list. My plan is to place wild-caught tenrecs within a box that can be converted into a maze of various layout and complexity (I’m extremely grateful to our super technician, Peter Stafford for making an adjustable maze which can be flat-packed for travel to Madagascar!).

Using a bat detector, I’m going to record the sounds produced by the animals both when they’re “at rest” just in the empty box and when faced with the task of moving through the maze to reach food at the other end. I’m going to observe and film the animals moving through the maze, both in daylight and under red-light conditions in darkness (hence the blackout curtains) and record the sounds they produce as they move. The idea is to test whether the animals’ call patterns (structure/frequency of calls) changes as they navigate their way past an obstacle in the maze. Bats are known to modulate their call frequencies when they hone in on their prey or to navigate their way past obstacles. I want to test whether there’s similar call modification in tenrecs which would provide evidence that the animals are actually using their echolocation sounds for navigation. It would be fascinating to understand more of how tenrecs use echolocation and to test whether other tenrec species can also echolocate.

It all sounds quite straightforward but I’ve experienced some of the vagaries of fieldwork in the past and I’m anticipating many more problems to come. I’ve received advice and war tales from researchers who have tried to study echolocation in shrews only to be thwarted by problems of distinguishing the animals’ calls from background sounds or the noise of the animal’s claws on a wooden base. Similarly, the tenrecs may not want to cooperate with my idea of moving from one end of the maze to another. I’m hoping that a nice juicy earthworm at the other end will act as the metaphorical carrot but there’s no way to know until we actually try it out. Furthermore, it might be difficult to distinguish sounds that say “I’m scared of being in this box” from sounds that the animals are using for navigation. Similarly, since we have neither the option nor inclination to experimentally blind or deafen the animals we won’t be able to completely exclude the possibility that the animals are using other sensory cues aside from acoustic navigation.

Even still, I’m hoping to get results which demonstrate the range of calls produced by tenrecs and which provide clues into how the animals use their acoustic behaviour to their advantage. Echolocation has involved independently in different animal lineages. Most interestingly, there is even clear evidence for convergence at the level of genetic sequences. Hopefully the data I gather over the next few weeks will add to our understanding of this fascinating story of convergence among tenrecs and other mammals.

And maybe we’ll spot a few lemurs on the way…

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: S. Finlay

Pity the Poor Pangolin

The pangolin is one of those lesser-known animals, at least in the West, most commonly seen as slightly dusty museum specimens (there’s one in our own zoology museum). Yet across their native lands they’re well known and very popular. Unfortunately this popularity is as food and traditional medicine. Indeed, recently the IUCN released a report saying, of the Chinese pangolin, “they are more than likely the most traded wild mammals globally”. This statement came following the first international conference on the conservation of pangolins, held by the IUCN. There is a very real fear that the Chinese pangolin and its relatives will be eaten to extinction.

I first became aware of the plight of the pangolin when I saw an article last year. A ship had run aground in a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Philippines (violating several laws in the process). When the ship was rescued it was found to contain 400 boxes of frozen pangolins, totalling 2,000 animals. All illegally caught, shipped and intended for trade on the black market. In searching for the news report I saw all that time ago I discovered that this was a remarkably common occurrence with illegal shipments being so widespread as to be almost mundane.

I first became aware of the plight of the pangolin when I saw an article last year. A ship had run aground in a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Philippines (violating several laws in the process). When the ship was rescued it was found to contain 400 boxes of frozen pangolins, totalling 2,000 animals. All illegally caught, shipped and intended for trade on the black market. In searching for the news report I saw all that time ago I discovered that this was a remarkably common occurrence with illegal shipments being so widespread as to be almost mundane.

So what is a pangolin and why are they in such high demand? The pangolin is a generic name for eight species of the genus Manis. The name comes from the Malay word pengguling which means “roller”, a nod to one of its key features: that of its ability to roll into a ball when threatened. Its alternative name, scaly anteater, acknowledges its other major features: the large scales that cover its body and its similarity in appearance and diet to the anteater. They are solitary, nocturnal and secretive creatures, found across Asia and Africa. Four species are found in Asia: the Indian pangolin (M. crassicaudata), the Chinese pangolin (M. pentadactyla), the Malayan pangolin (M. javanica) and the Philippine pangolin (M. culionensis) and four species are found in Africa: the cape pangolin (M. temmincki), the tree pangolin (M. tricuspis), the giant ground pangolin (M. gigantea) and the long-tailed pangolin (M. tetradactyla).

They are insectivorous, preferring ants and termites but branching out to other invertebrates, such as worms and crickets, when the mood or circumstances take them. Some are arboreal while others live mostly on the ground. They are sexually dimorphic with males being larger than females. Males have larger territories than females and their territories often cross, resulting in meetings that may lead to matings when the female is in oestrus. A single offspring is usually born and is carried by the mother on her tail for about 3 months until it is weaned. It stays with her for a further two months before leaving to find its own territory. It is not known how long pangolins live in the wild, though they have survived for 20 years in captivity.

They are insectivorous, preferring ants and termites but branching out to other invertebrates, such as worms and crickets, when the mood or circumstances take them. Some are arboreal while others live mostly on the ground. They are sexually dimorphic with males being larger than females. Males have larger territories than females and their territories often cross, resulting in meetings that may lead to matings when the female is in oestrus. A single offspring is usually born and is carried by the mother on her tail for about 3 months until it is weaned. It stays with her for a further two months before leaving to find its own territory. It is not known how long pangolins live in the wild, though they have survived for 20 years in captivity.

Pangolins do not, to my eyes at least, look particularly appetising, but there is clearly a demand for them. The best estimates are that between 91,000 and 183,000 were traded in the years 2011 to 2013. For an animal with a low reproductive rate this level of hunting is clearly unsustainable. And all this trade is illegal under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species). The demand is such that people are willing to risk prosecution and imprisonment. But what is driving this demand?

Unfortunately, it seems to be that much of the trade in pangolins is driven by the fact that eating them is seen as something of a status symbol. As they become rarer the prices go up, and this only adds to the appeal. An article from last year said that a restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City sold pangolins for between $600 and $700! Doing some ‘back of a napkin’ sums, this is about 3 months average wage in Vietnam, or the equivalent of spending about €10,000 on a main course in Ireland. There is no food that could be so tasty as to be worth that much. This is not about the quality of the food but the experience of being able to say to your friends “I have so much money I was able to eat pangolin last night”. I wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out that pangolin actually tasted pretty disgusting (I almost hope it does!).

The other use for pangolins is in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Ignoring the fact that “traditional” Chinese medicine was invented by Mao in the 1950s, pangolin scales are keratin, the same stuff that makes up your hair and nails. Yet still hundreds of kilos of scales enter the black market as they are said to be associated with the “liver and stomach channels” and treat a range of conditions mostly involving blood and pus.

The solution to the black market trade in pangolins is not easy. The rarer it gets the more valuable it becomes, both in itself and as a status symbol. I don’t know how you go about changing that attitude. Given that it seems to be considered an aphrodisiac in some regions, there is a lot of cultural baggage surrounding this poor creature. How do you try and convince people that eating pangolins will not increase your virility or that eating their scales will not improve your blood circulation? The easy answer is ‘education’ but this is only part of the solution because I doubt that many of the people eating pangolin really do so as an expensive form of Viagra, they do it because it’s an easy way to show they have money and that is a much harder cultural attitude to change.

The solution to the black market trade in pangolins is not easy. The rarer it gets the more valuable it becomes, both in itself and as a status symbol. I don’t know how you go about changing that attitude. Given that it seems to be considered an aphrodisiac in some regions, there is a lot of cultural baggage surrounding this poor creature. How do you try and convince people that eating pangolins will not increase your virility or that eating their scales will not improve your blood circulation? The easy answer is ‘education’ but this is only part of the solution because I doubt that many of the people eating pangolin really do so as an expensive form of Viagra, they do it because it’s an easy way to show they have money and that is a much harder cultural attitude to change.

So, pity the poor pangolin. Ignored in the West, revered in the East: as food, aphrodisiac, and alternative to chewing your nails.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image Sources:

Wikicommons

Scale image from http://bit.ly/1m7QGGW courtesy of TRAFFIC.

The Great Escapes

I was looking through some of my photos from volunteering in Namibia which reminded me of Houdini, the incorrigible baboon, who, no matter the precautions and security, would frequently turn up inside one of the guest’s houses rifling through their suitcases. This made me think it’d be fun to have a look at some of the most dangerous, daring and seemingly impossible animal escapes from zoos and aquariums over the years.

So many stories came up but these are my favourites:

Fu Manchu

This orangutan, a former resident of the Omaha zoo in the 1960s, was very often found peacefully reclining in the trees outside of his enclosure when his keepers arrived for work. Every door was locked and left intact so it took a long time, and a lot of threats of staff being fired, for them to catch him in the act. In the end it was a combination of stealth and CCTV that did it in for poor old Fu Manchu. He was observed, long after the zoo had closed and keepers gone home, climbing into one of the air vents and moving along the dry moat surrounding the enclosure until he reached a connecting furnace door. Here he managed to use his great strength to prise the door open just enough of slip a piece of wire through and pick the lock. Where he learned to pick locks nobody knew, but what also puzzled his keepers was that for the following days nobody could find the wire he had used and it wasn’t in the door. It wasn’t until some time later that one of his keepers noticed something sticking out of his mouth while he was eating; turns out he had been keeping the wire hidden and safe inside his cheek during the day!

Nikica the hippo

There have been a few stories of lost and escaped parrots and parakeets turning up in peoples’ back gardens- but what about a hippo!? That’s just what the people of Plavnica, Montenegro face every time there is a flood. The only thing is that it is always the same hippo: Nikica. The zoo is situated on the border with Albania and the region suffers frequent rises in water levels allowing Niikica to float seamlessly over her fence and out to explore the village. The best part of this story is the attitude of the people: everyone appears very relaxed at the idea of this two-tonne lady ambling around the village until the water gets back to a reasonable level. She even gets the VIP treatment at a local restaurant where she turns up for bread and a dip in their pool! Not so much an escape as a regular holiday.

Pacific octopus:

Octopuses are renowned for their ability to squeeze through a tight spot and contort their bodies into almost impossible shapes and positions to reach their destination. This makes them master escape artists. Indeed their stories have become the stuff of legend in aquariums (and some myths too). One story though that caught my attention simply because of the scale was that of pacific octopuses (which can reach an average length of 15-20ft) in the Steinhardt aquarium in San Francisco. The octopuses regularly found ways of sneaking along the drains from their tanks into neighbouring tanks to feast on the tasty crabs for a midnight snack. As one attempt to foil their escapes, the keepers put layers of Astroturf above the waterline in these tanks. Octopuses don’t like Astroturf as their tentacles can’t get good suction. The pacific octopuses however managed to find a way around these barriers and, on one occasion, a night watchman found the forty-pound octopus in the middle of the aquarium floor at 2.30AM!

Chuva the macaw:

One sunny afternoon at Vancouver zoo, the keepers decided to let the parrots out for a stroll on the grassy patches near the front of the zoo. The area was fenced and the birds had had their wings clipped so there wasn’t much danger of them straying far. Even when it was discovered that one of the macaws was missing, there wasn’t too much concern, as the birds can’t exactly run fast. The hours passed however and still no sign of Chuva. That is until a phone call was received from a group of bewildered visitors over 30miles away who had discovered a stow-away in their RV. It seems Chuva had managed to get through the fence and out into the parking lot where she spied the open door of the RV and hopped board for some AC, some fruit and the feel of the road!

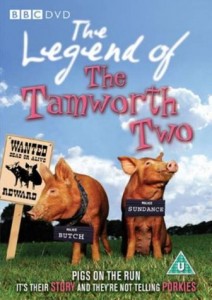

Butch and Sundance- The Tamworth Two

No story of escape would be complete for me without the famous pigs of 1998. Butch and Sundance were five month-old brother and sister Tamworth pigs that escaped form an abattoir while being unloaded from the lorry. They squeezed through a fence and swam across the River into nearby gardens. The pair was on the run for over a week, hiding in the dense thicket and entertaining local media and families. Their antics caused such a stir that, even though their owner still intended them for slaughter, they were purchased by the Daily Mail newspaper! They were eventually rounded up, Butch one day before Sundance, and sent to live out their days at the Rare Breeds Centre in Kent. Butch died at the ripe old age of 13 in 2010 and Sundance at 14 in 2011.

Author: Deirdre McClean, mccleadm[at]tcd.ie, @deirdremcclean1

Image Sources: BBC, Reuters, Wikimedia commons

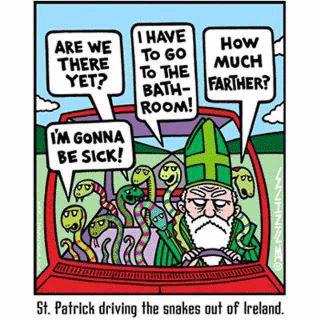

Island of Saints and Snakes?

Pubs, parades, shamrocks and snakes – an interesting mix of descriptors for any national holiday. Our patron saint of cultural identity (i.e. unashamed marketing of the Irish brand) was an affable fellow who, along with a historically proven love of Guinness and marching bands, is attributed with ridding our shores of serpentine beings. However, we give him more credit than he deserves.

As far as we know, Ireland never had any snakes. The reptiles couldn’t have survived during the last Ice Age. When the big freeze ended around 10,000 years ago it seems that snakes didn’t manage to beat the rising seas to get to the Emerald Isle. Ireland was cut off from Britain about 2,000 years before Britain was severed from mainland Europe. Three snake species colonised Britain but they never made the journey across the Irish Sea. But why not? It’s not that Ireland’s famously “balmy” weather was inherently inhospitable to reptiles. The common lizard managed to get here, seemingly in the post-Ice Age, pre-Irish Sea window that could have been open to snakes as well. To paraphrase sporting victories of the weekend, among reptiles it seems that lizards but not snakes were able to answer Ireland’s call…

Patrick didn’t drive the snakes into the sea but there’s a popular belief that this story is symbolic for how he rid of Ireland of pagan Druids. It’s attractively biblical in the telling; Christian missionary triumphs over snake-worshipping pagans. But there are a few problems with the story. For one thing, if there were never any snakes in Ireland then how could they have been used as symbols by Irish druids? Some writers suggest the prominence of snakes in Irish Celtic spirituality was a holdover from the Celts’ British/European ancestors who would have experience of the animals. Similarly, trade interactions could have brought stories of snakes from abroad.

Did Patrick banish the pagan Druids who were symbolised by animals that they had heard of but probably never seen? Nope. For one thing the story of banishing snakes; real or symbolic, was only attributed to the saint centuries after his death. Patrick was neither the first nor last in a string of missionaries to bring Christianity to Ireland. Furthermore, he neither banished the Druids nor cleansed Ireland of paganism and the final Christianisation of Ireland didn’t take place until at least the 14th century (a trend which we seem to be reversing now).

So Patrick didn’t banish snakes, Druids or paganism. Rather than ecological manager or societal revolutionary, arguably his main legacy is as the excuse for a day to paint the world green (or should that be blue…)

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: reddit.com

What’s it like to study Zoology?

Tell someone on the street that you study Zoology and you can pretty much guarantee what their follow up question will be; “so you want to work in the zoo?” Well not quite. Of course some zoology graduates conform to the general stereotypes; the zookeepers, conservation managers and wildlife handlers who keep the rest of us supplied with a steady stream of tales of adventurous exploits and envy-inducing pictures on Facebook. But that is only one side of what you can do as a zoologist. It’s not all about frolicking with cute animals. There’s a healthy dose of molecular and lab-based research, theoretical studies and unavoidable number crunching which make up significant portions of life as a zoologist. Not to mention the diverse career opportunities, in areas such as science communication, education, policy and management, that are available to zoologists who venture beyond traditional research jobs.

A group of Transition Year students (15/16 year olds) recently spent a week in the department learning about what it’s like to study and work as a zoologist. Some of their questions and misconceptions prompted me to write this blog. Consider it the lowdown on zoological life if you will.

Zoology is not just about cute animals

If your interest in zoology stems from a desire to spend your days playing with puppies or equivalent bundles of cuteness then be warned. Such opportunities do arise during a degree course but they are relatively limited. You will spend more time in lecture rooms, dissecting dead animals or behind a computer than you will interacting with live animals. Of course field courses, summer research opportunities and final year undergraduate projects do offer many opportunities for hands-on, practical experience but these are the exceptions rather than the rule for life as an undergraduate zoologist. Post-graduation is another story entirely: there’s puppies, meerkats, elephants and dolphins aplenty if that’s what you want!

Zoology is not stamp collecting

Modern zoology stems from the long scientific traditions of enthusiastic naturalists: the genteel country gentlemen who wiled away the hours with contemplations of beetles and the exotic explorers who bravely ventured forth into unknown lands. These origins have created a common misconception that modern zoology follows the same veins; we may collect DNA sequences rather than butterflies now but surely it’s all just descriptive stamp-collecting at heart? Well, no. The methods and techniques used in zoology research are just as scientifically rigorous and complex as the “machines that go ping” which grace any physics or chemistry lab. Zoology is no more exempt from number crunching and computational methods than any other scientific discipline. You don’t have to be a maths whizz or computer nerd but a career in zoology, no matter what branch, will inevitably involve quantitative and not just qualitative analyses.

(Most) Zoologists are not hippy dippy animal lovers

A common misconception about being a zoologist is that it’s a just a fancier term for people who are only concerned with animal rights and issues. So we should all be strict vegans who spend our holidays trying to board Japanese whaling ships and we would rather halt economic progress than lose a single species of ant to extinction. Inevitably there is an element of truth to these ideas. We chose to study zoology because we’re fascinated by the natural world and the logical progression of such interests is a desire to protect and conserve all aspects of life on our planet. But our pro-animal tendencies don’t equate to making us anti-human! Zoology teaches us to develop and apply appropriate, practical and realistic management and conservation actions to protect biodiversity while also enhancing human economic and social livelihoods.

Zoologists don’t just do field work

I chose to study science generally and zoology more specifically because I was adamant that I didn’t want to be stuck at a desk in an office. Guess where I spend most of my days now? Zoology isn’t all about trekking through jungles or diving on ocean reefs. Most research zoologists spend the majority of their time indoors whether that’s at the lab bench or behind a desk. The difference lies in the fact that, unlike a “normal” desk job, zoology provides plenty of opportunities to get out of the office whether that’s catching vultures in Swaziland, perusing museum collections, island hopping in Indonesia or traveling the world for conferences. These are the undoubted highlights of any research project but they represent the cream of zoological life: usually you will spend far more time working at your computer than exploring the outside world.

Zoology is…great!

Don’t be fooled by the apparent negativity of the points above. I love studying zoology. I love the diversity of the subject, the breadth of knowledge to which we are exposed, the fascinating research questions we study and our undeniably awesome opportunities to travel. I fell into zoology by accident rather than design and I could not be happier with my choice of subject. Research careers in zoology are varied and exciting but a zoology degree is also great preparation for so many opportunities beyond the realms of traditional research. Zoology is suited to people who are interested in nature, the environment, biology in general or anyone who is a confirmed lifelong disciple of Sir David. Zoologists are well equipped to take up any variety of career paths.

Our horizons both include and extend beyond the zoo gates!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: Wikicommons