Following the influence of science writers such as S.J. Gould, I always try to look back at the historical perspectives of what I’m studying. These days I’m playing with 3Gb trees so I was delighted by Mindell’s 2013 Systematic Biology publication about the Tree of Life.

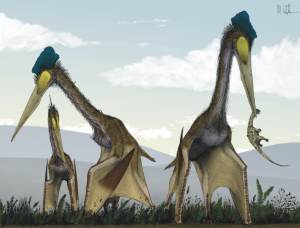

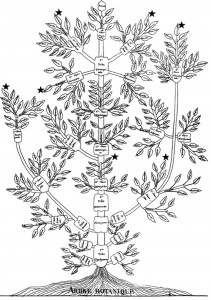

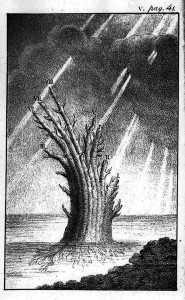

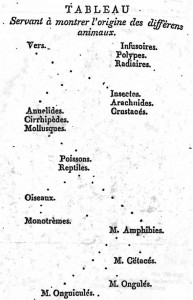

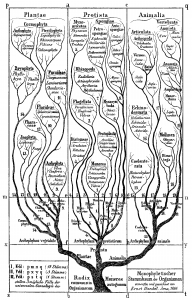

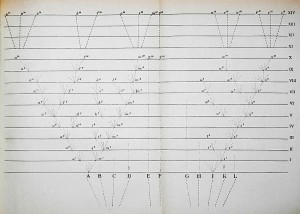

The idea of placing species into the so called Tree of Life emerged before the Origin of Species with works such as Augier’s Arbre Botanique (1801) (Fig. 1) and Eichwald’s tree (1829 – possibly inspired by Pallas’s 1766 work) (Fig. 1). But the spreading of such trees began only after publications of Lamarck’s scheme (1809,Fig. 2), Darwin’s famous sketched drawing (1859 – Fig. 3) and Haeckel’s beautiful tree (1866 – Fig. 2). It is only within an evolutionary framework that these representations of the relationships among organisms make sense: the idea of descent with modification.

Figure 1: Augier’s Arbre Botanique (1801) & Eichwald’s tree (1829) – from Mindell 2013 (Fig.1)

Figure 2: Lamarck’s scheme (1809) & Haeckel’s tree (1866) – from Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Darwin’s Origin of Species unique figure (1859) – from Wikimedia Commons

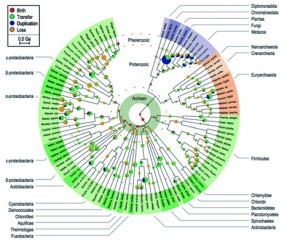

From that point, we all know how the story continued; from Darwin’s sketch (Fig. 3) to modern phylogenomics (fig. 4). Our understanding of the Tree of Life progressed from Simpson’s (this one, not this one) cladistic methods for looking at morphological relations among vertebrates, through to the discovery of DNA, the first molecular clock and, eventually, the use of complicated Bayesian stuff. Depictions of the Tree of Life evolved from something like a cypress (a nice, straight tree with Neil Armstrong at the top surrounded by monkeys and mosses and jelly fish near the roots) to a three-rooted shrub full of immense dead branches near the centre. If you look at the figures included in this blog, the changes in our understanding of the tree are clear: a gradual reduction of anthropocentrism and inclusion of microscopic organisms.

Figure 4: Tree of Life from David and Alm (2011) – from David and Alm 2011 (Sup. Fig. 15)

So what should we do next? Should we just expand the dataset until we have all the species and all their genome plotted in the Tree of Life? Hopefully there are still lots of less boring things left to do for researchers working in this area today… Two questions are (in my mind) really important to look at: is the Tree of Life only the result of descent with modification and what should we put in the tree?

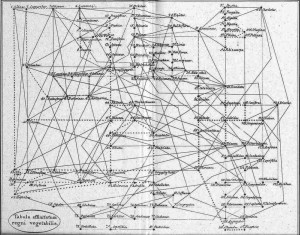

For the first question, it appears more and more clear nowadays that the Tree of Life is not really a tree but rather something along the lines of a tree-shaped web. Regarding Archaea and Bacteria alone (the majority of organisms in the tree), it is estimated that at least 81% of their genes have been laterally transferred among lineages at some time in the past. This phenomenon is also becoming increasingly evident among Eukaryotes (even among vertebrates!) and recognition of these events should lead to a more web-shaped “Tree” of Life. Incidentally, it is interesting to note that Batsch recognised this web structure in plants as early as 1802 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Batsch’s web of plants (1802) – from Mindell 2013 (Fig.1)

Regarding the second question, asking what can be included in the tree of life comes down to how we determine what is living. I remember one question that a classmates had in my phylogenetic lectures; “What is the out group of the tree of life?” The lecturer had just said that a tree without an out group is not valid. The resulting discussion turned into a really long (and interesting) debate about viruses – the question being whether we should put the viruses in the tree of life? We might define living organisms by entities that can replicate their own DNA. So you could argue that if viruses cannot achieve this independent replication then we should prune them out of our tree. Haha ! But wait, it’s not so easy: although most viruses require host cells for reproduction, so do many other “living” organisms like Richettsia or Chlamydia. In addition, some viruses have many genes involved in DNA replication so how should their self-replication abilities be classed ?

Mindell conclude by quoting Brooks and van Veller (2008): “There are two choices. Do we classify a tree with [lateral transfers], or do we try to classify a [lateral transfer] network? If we wish our classifications to reflect what we think we know about evolution, it seems that we will have to opt for the first alternative.” Does this mean that we should go for a tree shaped web including viruses? Let see how the debate will go on…

Author

Thomas Guillerme : guillert[at]tcd.ie

Photo credits

wikimedia commons

Mindell 2013

David & Alm 2011