It’s rare to come across a sci-fi movie that isn’t loaded with technobabble or scientific terms that are used ever so incorrectly. In fact, a lot of the Hollywood blockbusters are guilty of mincing the scientific words and concepts for entertainment value: “The Day After Tomorrow”, “Armageddon”, “Lucy”, “The Core”, to name but a few.

In short, Science itself has been drastically misrepresented by the Hollywood industry.

Then along came Ridley Scott’s sci-fi epic “The Martian”.

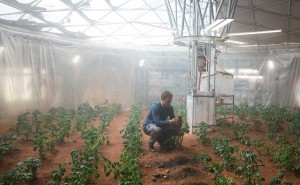

Based on the sci-fi novel by Andy Weir, it tells the story of astronaut Mark Watney (Matt Damon), who’s left stranded on a Mars space station after being presumed dead by his crew. Despite his circumstances, Mark manages to survive for over 500 days by employing his ingenuity as a botanist to grow and harvest potatoes on Martian soil.

After watching our astro-botany protagonsit build his very own Martian farm (synthesizing water and all) in a manner McGyver would be proud of, the question was working away in the back of my mind: Could this really happen? Or was Hollywood once again selling the science short?

Let’s put it to the test.

1) Solely spuds for survival?

Could one man live off Maris Pipers for nearly a year?

Yes.

Yes he could.

In 2010, Chris Voigt from the Washington State Potato Commission lived off nothing but potatoes for 2 months as a publicity stunt promoting their nutritional benefits. And lived to tell/blog the tale.

Potatoes are a source of high-level carbohydrates, providing around 163 calories each. They also contain essential nutrients such as magnesium, potassium folate, vitamins B6 &C, low levels of protein and dietary fibre in the skins.

However, supplemental vitamins A, E and K would be needed to stop our Martian protagonist from going blind.

Added to the fact that Mars has one-third the gravitational pull of Earth, the potatoes’ energy content can go the extra mile now that Mark is one-third his own weight, hence expending less energy than that on his home planet!

2) Life on Mars’ soil?

One of the biggest challenges faced with Martian agriculture is the lack of anything living in the soil – particularly bacteria that can fix Nitrogen, which is an essential for plant growth.

Luckily enough, Mark found access to the space stations’ vacuum-packaged poo to use as manure – giving a new lease of life on the Red Planet’s potato plantation.

While the thought of using you own fecal matter to fertilize your food may make some sick to their stomach, this is practiced today under the guise of “Biosolids”. As a fertilizer, they fetch up to £27 per tonne in dry mass for their nutrient content.

Also, we’re assuming Mark harvested his own poo, hence is only exposing himself to his own batch of pathogens and bacteria from his own gut. Otherwise he may make himself very sick from fiddling with foreign fecal matter!

3) Safe soil to sow on?

Mars soils consist of finely broken up basaltic fragments derived from volcanic gas emissions, which are highly enriched in sulphur (which may explain why nothing is living in it).

But the soil also contains salts called perchlorates, which were detected by NASA’s Phoenix lander in May 2008 in the form of calcium perchlorate.

At high enough levels, perchlorates – a key component in solid rocket fuel – can lead to thyroid problems, which makes it quite toxic to humans.

If 0.6% of Mars’ soil was made up of perchlorates (hence 60 grams/kg) how toxic would this be for Mark Watney?

A report from the Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (ATSDR) highlights a longitudinal study of 2 healthy volunteer groups consuming perchlorate treatments for i) 35mg for 2 weeks or ii) 3mg for 6 months. At the end of both treatments, with both groups consuming up to 0.55g of this salt were found to experience no abnormal thyroid functionality.

But at such small doses, it doesn’t provide enough sound evidence that Mark wouldn’t have his thyroid tampered by the perchlorates percolating into the potatoes.

In summary, can one astro-botanist:

i) survive on just potatoes? [Yes]

ii) make fertile Martian soil? [Yes]

iii) work around the soil’s “toxic” properties? [Jury’s out for now]

With the discrepancy of knowledge for our last scenario letting us down, the remaining facts are air-tight: Mark Watney most likely could have sustained himself on Mars with just potatoes.

As I’ve said before, a lot of Hollywood’s movies have sold Science a bit short in the past. But the Oscar-nominated* sci-fi flick has stepped up to the mark to produce not only a stellar cast and production, but to produce an adapted screenplay that is doesn’t lose sight of its tale of humanity and the triumph of the human spirit by “sciencing the shit out of this.”

*Currently nominated for Best Picture, Best Actor and Best Production Design.

Biosolids in Ireland

http://www.environ.ie/en/Publications/Environment/Water/FileDownLoad,17228,en.pdf

ATSDR Perchlorates Report

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/phs/phs.asp?id=892&tid=181

Simon O’ Carroll – Graduating with a B.A. (Mod.) in Zoology in 2015, Simon is currently doing an Master’s in Conservation and Biodiversity at the University of Exeter.

Image Credits: io9.gizmodo.com, http://modernfarmer.com/2015/10/can-you-grow-plants-on-mars/