Do voluntary work and outreach activities really make much of a difference in an environmental career? Yes, in general, but not for the reasons you might expect.

Picture this: you have finally found an amazing career path that you really want to follow. It is engaging and challenging and you will make a positive contribution to the world. But before the excitement carries you away you discover a big problem – other people have found out about your dream job and they want it too. A good degree is a great start, but if you want to land that first job or move up the ranks, you need something more. That was the challenge facing me as an aspiring ecologist nearly ten years ago, and the question I asked was this: how can I make myself stand out?

Work for free

The advice pages tell you the same thing again and again – it is all about qualifications, skills and experience. But if the qualifications are not enough to get the job, then how do you get the skills and experience? Well, you work for free – and frequently from a very young age. Career profiles of successful ecologists often detail the work they did for the local wildlife group from the age of six, when they were apparently already experts in hedgerow flora and bog moss. For the rest of us who were more interested in Lego and finger painting at that age, it can be a bit disheartening.

Putting it into practice

For me, collecting additional work hours began in college. I started doing free or badly paid field work during my undergraduate, lectured during my masters, and as a consultant ecologist I did as many training courses as I could. There is an embarrassment of acronyms in the Professional Memberships section of my CV. To supplement formal training, I took on some voluntary bird and plant surveys. A few years ago, I started to help organise an academic conference and environmental career fair in my spare time.

Time for a reckoning

Now, my supervisor tells me that maybe I have gone a bit far. Is it really possible to be an active member of over ten organisations and still do a PhD in three years? Given the time and money involved, can I afford it? Really, how have I actually ever benefitted from being involved in such a breadth of organisations? Should I cut down?

Volunteering and training can give you hard skills, but the biggest dividends I noticed are fuzzier and hard to quantify. Networking opportunities might be the biggest benefit. When I finished my masters, it was contacts I had built up over the previous two years who helped me to get a decent job. People I have met through volunteer work advised me when I wanted to go back to college, helped me to find funding and they are there whenever I pick up the phone with a question.

Working outside your comfort zone will increase your confidence. The thought of selling myself or raising funds used to fill me with toe-curling shame and embarrassment, until I had to fund-raise for a national conference. Being forced to do it helped me to get over my reluctance to ask for cash. Without that experience, I don’t think I could have asked for the funding required for my PhD.

Broadening your perspective can be a huge benefit at work. As a volunteer, you can meet people with a range of backgrounds and training, and this is very helpful when it comes to team work or engaging with clients. Having recently worked with zoologists, engineers, educators and students made moving from botanical consultancy to a multidisciplinary research project merely intimidating instead of being terrifying and insurmountable.

What do do?

Surprisingly, my experience seems to be quite normal. Research shows that volunteering helps your job prospects whatever sector you are in, but not for the reasons you might expect. By taking on volunteer work, you prove yourself to be motivated and engaged, but you are not necessarily perceived as being more skilled or qualified. Who you know is as important as what you know, and in some cases motivation and drive can trump academic skills. For me, this means I will keep on doing voluntary work, but be smarter about it. I have been lucky to get plenty of in the course of my PhD, so I will focus on management and networking activities. I am looking forward to it. From now on, I will be socialising for a cause, enjoying the illusion that with each sip of wine I am boosting my career prospects and helping to make the world a better place.

Author

Aoife Delaney, amdelane[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/natureplus

On Friday September 25, the School of Natural Sciences and Trinity Centre for Biodiversity Research will present Discover Life! in the Zoology and Botany buildings at Trinity College Dublin.

On Friday September 25, the School of Natural Sciences and Trinity Centre for Biodiversity Research will present Discover Life! in the Zoology and Botany buildings at Trinity College Dublin.

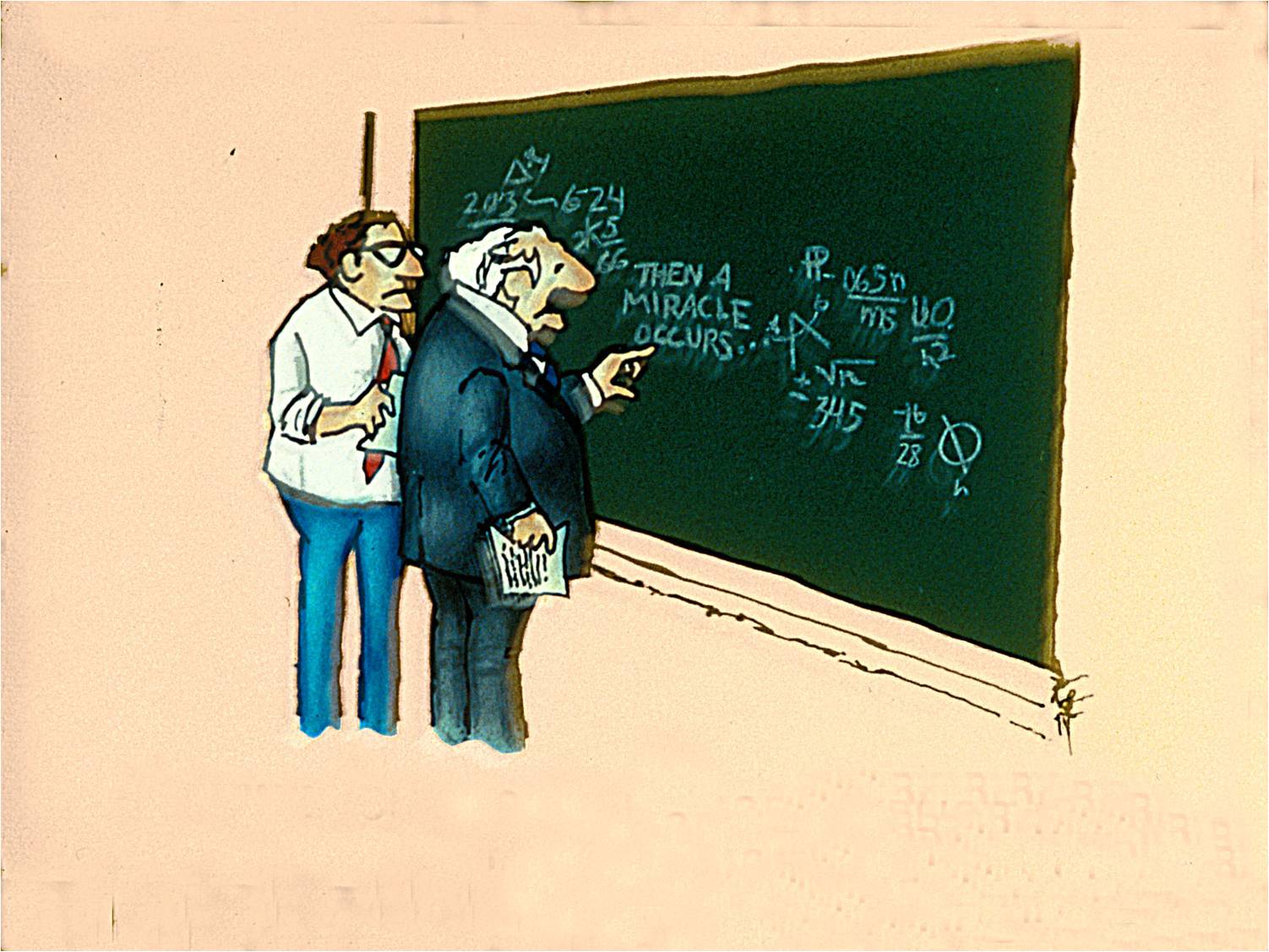

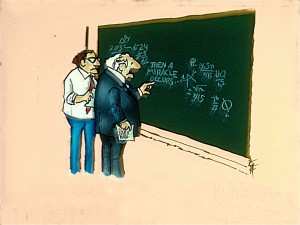

Scientists as a demographic group tend to be atheists.

Scientists as a demographic group tend to be atheists.

Thanks to everyone who entered the competition. This time around our panel of judges deemed Deirdre McClean’s entry to be the worthy winner. Her picture of a

Thanks to everyone who entered the competition. This time around our panel of judges deemed Deirdre McClean’s entry to be the worthy winner. Her picture of a

“

“