Our understanding of how species interact and evolve depends on accurate knowledge of the species that exist on Earth. There are still many species to be identified, however, even in evolutionarily significant regions such as Wallacea in central Indonesia, site of Alfred Russel Wallace’s pioneering work. Our new paper, completed jointly with researchers from Universitas Halu Oleo and just published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, draws on work carried out in Wallacea to identify multiple unrecognised species in the beautiful sunbird family. Made using modern genetic, acoustic, and statistical techniques, these discoveries add to our understanding of how life evolved in this region and reinforce some of Wallace’s original ideas.

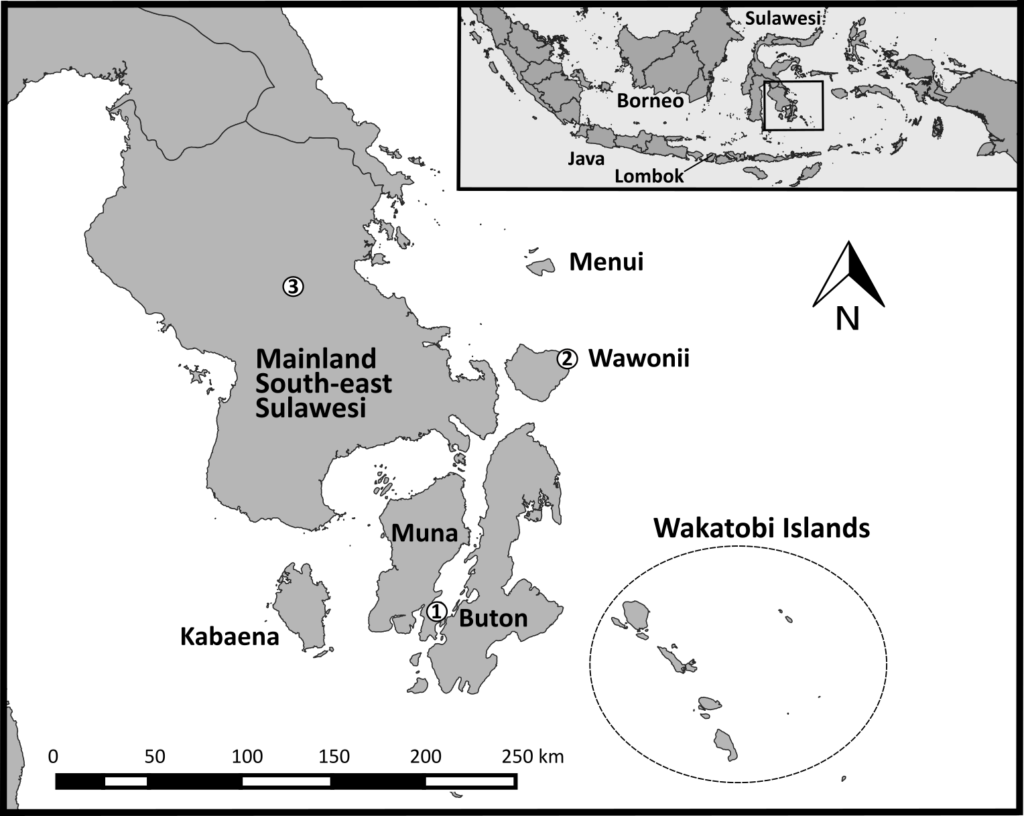

The key discovery is the “Wakatobi Sunbird Cinnyris infrenatus”, a species endemic to the small islands of the Wakatobi archipelago, off Southeast Sulawesi in central Indonesia. The Wakatobi Islands have been separated from other landmasses since they first rose out of the sea, and so there has been plenty of time for their populations to evolve in isolation and produce endemic taxa, found nowhere else on Earth. The Wakatobi Islands have been recognised as a Key Biodiversity Area for their importance to the survival of biodiversity. The Wakatobi Sunbird is the latest endemic species to be identified by our research group, following previous work on the Wakatobi Flowerpecker and the double discovery of the Wakatobi White-eye and Wangi-wangi White-eye. It’s important that we know all of the species of Southeast Sulawesi and the Wakatobi Islands, because this region acts as a “natural laboratory” for the study of evolutionary processes such as cryptic sexual dimorphism, the “supertramp strategy”, and the links between behaviour and population divergence. The Wakatobi Sunbird is currently treated as a subspecies of the widespread Olive-backed Sunbird (Cinnyris jugularis), but our findings indicate that the Olive-backed Sunbird is actually made up of at least 4 reproductively isolated species.

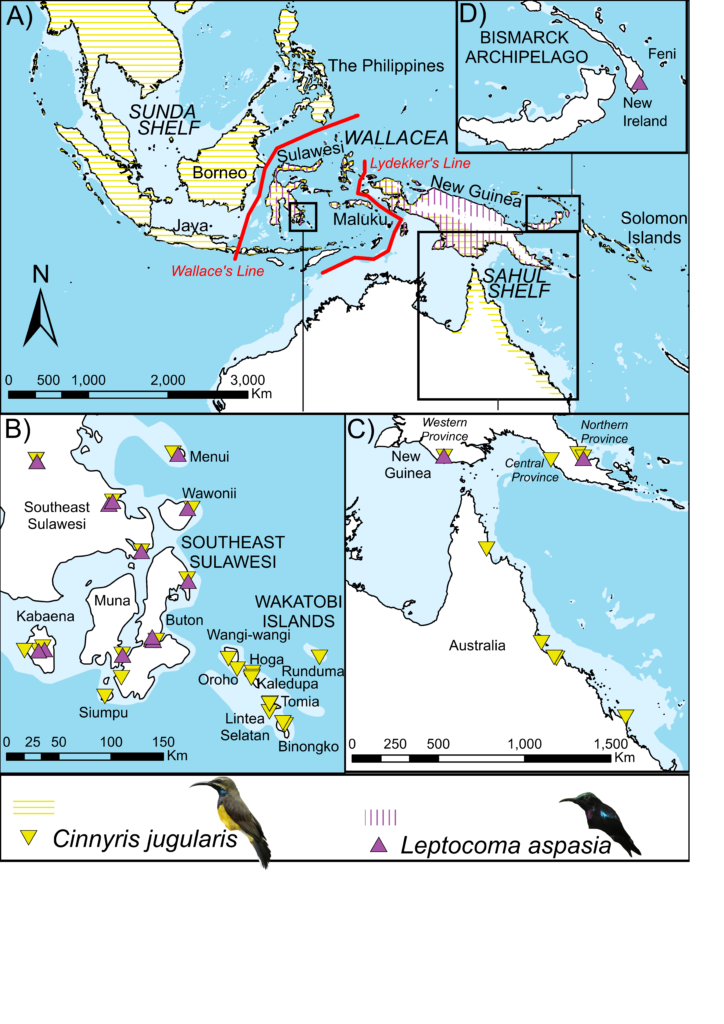

The sunbirds (Nectariniidae) fill a similar niche in Africa, Asia, and Australia to the hummingbirds of the Americas. They are small birds with long bills that help them extract nectar from flowers. Like the hummingbirds, many sunbirds (males particularly) exhibit brightly coloured plumage, with beautiful iridescent or “metallic” feathers that reflect the sunlight. In fact, the naturalist William Jardine tells us in his 1843 volume on the sunbirds that sunbirds get their name “from their brightly-tinted dress, appearing in higher splendour when played on by the sun-beams”. For hundreds of years, ornithologists have used the patterns and colours of these feathers to identify sunbird species. Now, however, we can combine multiple forms of data to uncover patterns that weren’t clear from plumage alone. Our paper also looked at the Black Sunbird (Leptocoma aspasia), a species with male plumage that’s hard to examine because it mostly looks jet-black, except when the sun hits it in the right way to reveal other colours. We found a genetic split in this species that had not been suggested by any previous work, probably due to its plumage being less informative.

Finding species like these isn’t just interesting for its own sake. It is also our best evidence to understand how evolution produces new species. This is particularly interesting in a region like Wallacea, which played such a significant role in the development of evolutionary biology. The observations that Wallace made around this region led him to discover evolution by natural selection, work which was published jointly with Charles Darwin in 1858 in the same journal where our sunbird paper has just appeared.

One of the observations that inspired Wallace’s evolutionary thinking was the importance of biogeographic barriers. Wallace noticed that the animals found on Sulawesi are markedly different from those on neighbouring Borneo, evidence that species would evolve on one island and then have difficulty crossing over. This boundary came to be known as Wallace’s Line. We now understand that it represents the beginning of the deep waters of the Wallacea region, which persisted even when sea levels were lower, unlike the shallower waters of the adjoining Sunda Shelf which gave rise to land bridges. A similar barrier to the east came to be known as Lydekker’s Line. As seen in the map below, the range of the Olive-backed Sunbird (in yellow) is currently thought to cross both Wallace’s Line and Lydekker’s Line, while the Black Sunbird (in purple) stops at Wallace’s Line but crosses Lydekker’s Line. It’s quite remarkable to imagine these dainty little birds maintaining gene flow across barriers which block so many other organisms! Our work, however, has indicated that the Olive-backed Sunbird populations on either side of Wallace’s Line actually represent separate species. The same is true of Black Sunbird populations divided by Lydekker’s Line. Modern evidence has actually reinforced Wallace’s original ideas, showing once again that these Lines represent significant biogeographic barriers that block gene flow in most animals.

Both evolutionary biologists and ecologists are gaining new insights from large datasets on the traits and genomics of species. However, as these datasets are organised by species, they rely on our species lists being accurate in the first place. Data from “species” like the Olive-backed Sunbird or Black Sunbird might prove misleading, as each of these actually represent multiple species. Meanwhile, a small population like that of the Wakatobi Sunbird may not be included in such a dataset at all if it isn’t recognised as a species.

To quote an 1863 paper by Wallace, the world’s species represent “the individual letters which go to make up one of the volumes of our earth’s history and, as a few lost letters may make a sentence unintelligible, so the extinction of the numerous forms of life which the progress of cultivation invariably entails will necessarily render obscure this invaluable record of the past”. It is therefore an irrevocable loss to the world, to humanity, and to science when a species goes extinct while still unrecognised, “uncared for and unknown”.

While the Wakatobi Islands are biogeographically “remote” due to their small size and the permanent water barriers that surround them, it is worth noting that they are not the stereotypical “desert islands” Western readers may imagine. The islands have been part of important shipping lanes since at least the 14th century, and the people of the Wakatobi are known for their maritime traditions and unique language. As Dr David Kelly, the second author on the recent paper remarked: “The identification of the Wakatobi Sunbird serves to remind us that biodiversity is everywhere. This bird wasn’t found in a remote rainforest, but along the scrubby margins of busy towns and villages. Let us hope the children of the Wakatobi will be able to enjoy these special birds for generations to come.”

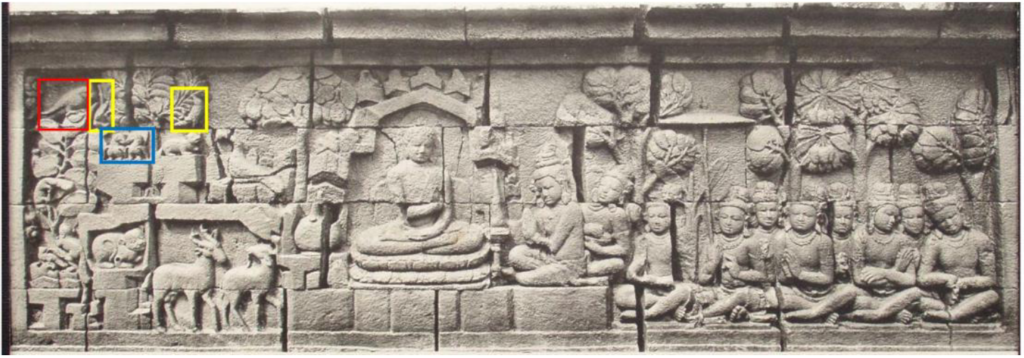

The beauty of the sunbirds has attracted scientists and artists for many years. Elsewhere in Indonesia, Java’s Borobudur (the largest Buddhist temple in the world, constructed in the 8th or 9th century CE) displays carvings of Olive-backed Sunbirds drinking nectar on its walls. The researchers who identified these carvings hypothesise that this symbolises the Buddhist ideal of enlightenment. Over a thousand years later, sunbirds are still enlightening us on the origin of species.

To find out more, read our paper in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society here: https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac081