We’ve all been there, trying to get some out of reach object only to dejectedly ask for the assistance of another. Turns out, this behavior has been with us for most of our lives. It is known that children as young as 12 months will start to point at certain objects that they desire but are, for obvious reasons, unable to obtain (Figure 2). This behaviour is known as imperative pointing and, as it turns out, you don’t even need to point to be able to do it. In fact, gaze alteration, the process of looking between the desired object and a specific individual, is seen as an analog of this in our four-legged friends, the canines. This behavior has been widely examined in domesticated dogs, who humans have a long history of cohabitation with. Indeed, many of us can probably offer anecdotal evidence of this in our own dogs, be it looking at treats on a shelf, or their favourite toys on kitchen tabletops. However, surprisingly, it has never been studied in wolves, the wild relatives of our beloved pooches. In 2016, Heberlein et al. set to change this, and their findings have some important implications, not least concerning our understanding of the very domestication of dogs itself.

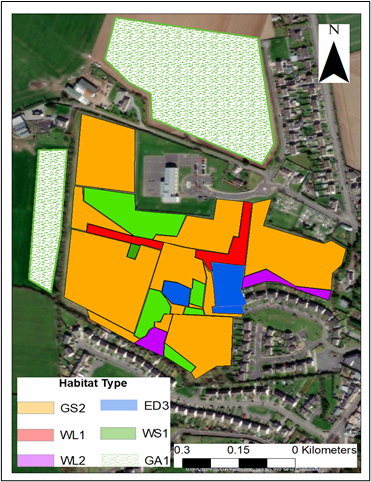

The experimental premise was relatively simple. A group of grey wolves (subspecies: timber wolf) and a group of dogs (breed not given), were both obtained from animal shelters in Europe and were raised from puppyhood with daily human interaction. When the canines were around 2 years old, the experiment began with a pre-feeding and training phase. This involved an experimental room with 3 boxes (Figure 3), each too high for the canines to reach by jumping, the poor guys. In this phase, food was first shown to the animals, one animal at a time, and then clearly placed in each of the boxes. If the animal looked at the box and then at the human, the human would automatically get the food for them. The wolves and dogs were then introduced to 2 new humans, a mean competitor who would steal the food, and a helpful cooperator, who would share any food the animals identified. This whole process would serve to inform the canines that the humans could provide them with out of reach food, but that only the cooperator would actually give them any of it. Why go through all this trouble you may ask? Well, turns out there were some very clever scientists involved in the experiment. Those involved wanted to avoid the possibility that gaze alteration for food could simply be the result of a food human association, i.e., if I stare at a box and then a human, then the human must give me food. If gaze alteration reflects some true communicative intention on the part of the animals, then one would expect that they should ask for help mainly from the cooperative human, I know I definitely prefer working with cooperative humans. Once trained, the test was ready to begin.

The actual experiment involved a tasty sausage being presented to a lone wolf/dog and then being hidden in one of 3 boxes located in the room, the same room used in pre-training. Then, either the cooperative human or the competitive human, the same humans the animals had been trained with, entered the room. They would passively observe the animal for 1 minute after which they would go to the box they believed the animal was looking at. If correct then the sausage would wither be given to the animal, if the cooperator was present, or eaten by the human, if the competitor was present. The process was repeated a total of 4 times, twice with each type of human.

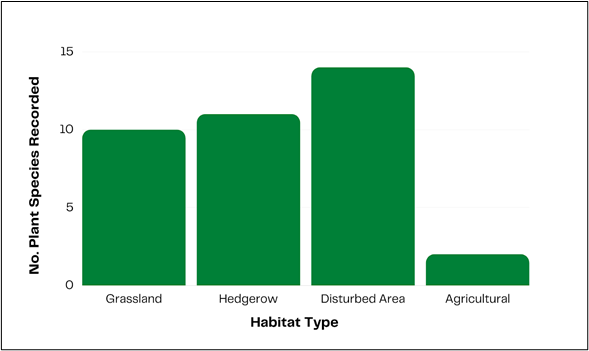

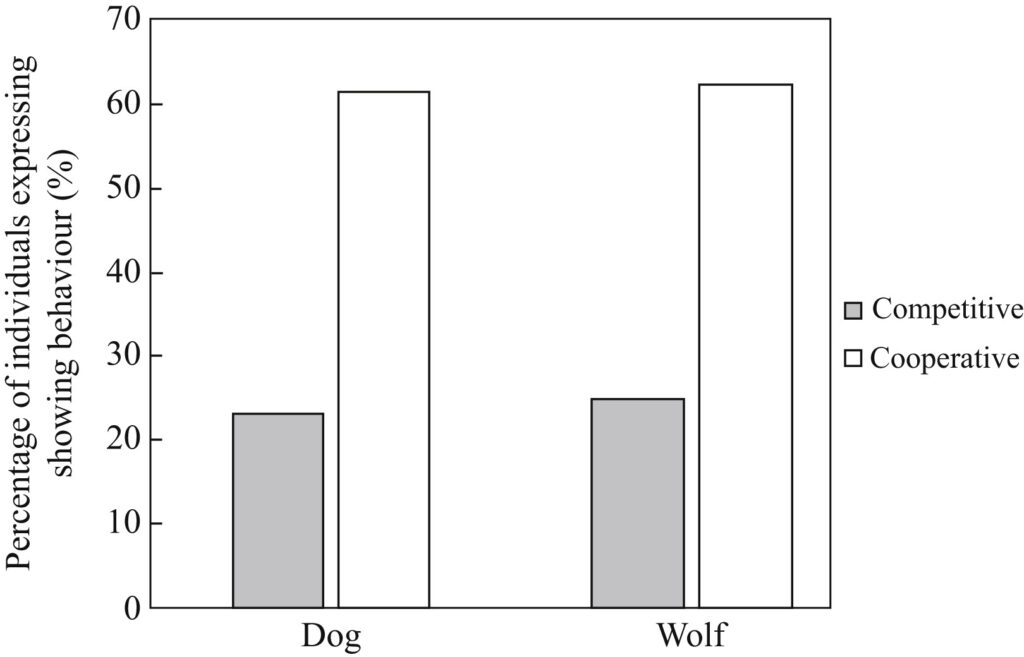

The results were incredibly interesting. In most cases, the canines, both wolves and dogs, showed the correct food location to the cooperator but not the competitor (P = 0.006) (Figure 4). Importantly, there was no difference between this behaviour between the two species (P = 0.24). As an aside, P values are statistical values that tell you if there is a significant difference between two things. All you need to know is 1) Any P value less than 0.05 means that the event is unlikely to have happened by chance and 2) That scientists are very fond of including them in their papers. In any case, what’s even more interesting is what these results can tell us about their evolutionary histories. While both directed the cooperative human to the food box, wolves spent more time looking at the food itself when compared to the dogs (P = 0.03). This may reflect a higher food motivation present in wolves. Intuitively this makes sense, as, while some of us would surely like them to be, wolves are not pets and so need to hunt for food themselves. In addition, the ability of dogs to referentially communicate with humans was thought to be a result of their domestication and close association with us ever since. The results of this experiment would, however, suggest that this ability was at least present in the common ancestor of the wolves and domestic dogs. Therefore, rather than this communication being a product of domestication, it is more likely that the skill of referential communication had evolved in canines to promote the social coordination needed for group living, i.e., living in their packs. In other words, the common ancestor of today’s canines may have also been a good boy.

In summary, dogs, are not alone in their ability to ability to referentially communicate with us. This ability is shared with the grey wolf and the choice to work with a cooperative human over a competitive one provides evidence that there is some conscious thought in this decision-making process (both in dogs and wolves). While this raises important questions about the evolutionary histories of these animals, more intriguing questions remain. Namely, what other well-known traits of dogs are also present, but undiscovered, in wolves. Personally, I am very much excited to find out.

For more information on this topic, you can read the paper discussed here (free of charge)

Blog written by Niall Moore, a final year undergraduate student, as part of an assignment writing blogs about an animal behaviour paper!