by Midori Yajima

How unlikely it is to think that many people who decided to dedicate themselves to a natural sciences-related field wondered at least once about the life of an eighteenth-century naturalist?

Picture Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin or Joseph Banks expeditions, or René Malaise and Gustav Eisen‘s impressive efforts in gathering human specimens and artefacts. How about Roderick Murchinson and his geological surveys around the world, or Hans Sloane, whose collections contributed to the foundation of London’s beloved British Museum? The imaginaries of explorers crossing oceans towards yet unknown territories, observing and sampling specimens never seen before, naming and using them to interpret the world, are striking, to say the least.

Nevertheless, other narratives are growing beside these settled imaginaries. It is increasingly recognised how those exact figures were far from the idea we have of them: solitary geniuses and intrepid explorers, nothing related to the politics and economies of their time. Instead, their journeys would rest on the routes of British imperialism, making use of the slave trade in the case of Sloane,1 or be sponsored by intelligence operations on foreign valuable minerals and local policies such as the case of Murchinson2. Even an important institution such as the Royal Botanic Garden in Kew now acknowledges how the boost that botanical research saw at the time was supported by interests in new profitable plants3. Likewise, it is recognised how the global network of botanic gardens emerged not only to create pleasant green spaces but also to have experimental facilities dedicated to researching those exotic new plants for valuable products. As a matter of fact, the search and cultivation of plants such as the rubber tree, a source of such a profitable material, or the Cinchona tree, from which the compound quinine was isolated and used against malaria by the occupying forces in the tropics, have been central to the expansion of the British empire4. The very same collection of animal, plant and human samples can be considered to be driven by similar dynamics. What was discovered in the colonised territories was taken, shipped to the collectors’ homelands, and then housed in centres that, in turn, expanded to accommodate the increasing flow of materials, being a source of knowledge for the benefit of their host institutions. This colonial dimension of the sciences that study nature remained unaddressed in the mainstream imaginaries, although some already glimpsed it. Like Sir Ronald Ross, a doctor engaged in the fight against malaria in the Sierra Leone colonies, who in 1899 publicly expressed how the success of imperialism in the following century would largely depend on success with the microscope 5.

Much has been written about “how modern sciences were built on a system that exploited millions of people, at the same time justifying and supporting it to an extent that greatly influenced how Western people view other ethnic groups and countries”6. At the same time, others point out that “one should not fall into the prospective error of asking nineteenth-century men to reason with post-colonial categories developed after World War II” 7. Likewise, those who work or are interested in these fields today might easily feel far from this legacy, either because of the time that has passed since that era or because of the desk-based nature of their research. Why think about it then? Wasn’t this a blog just about ecology and evolution?

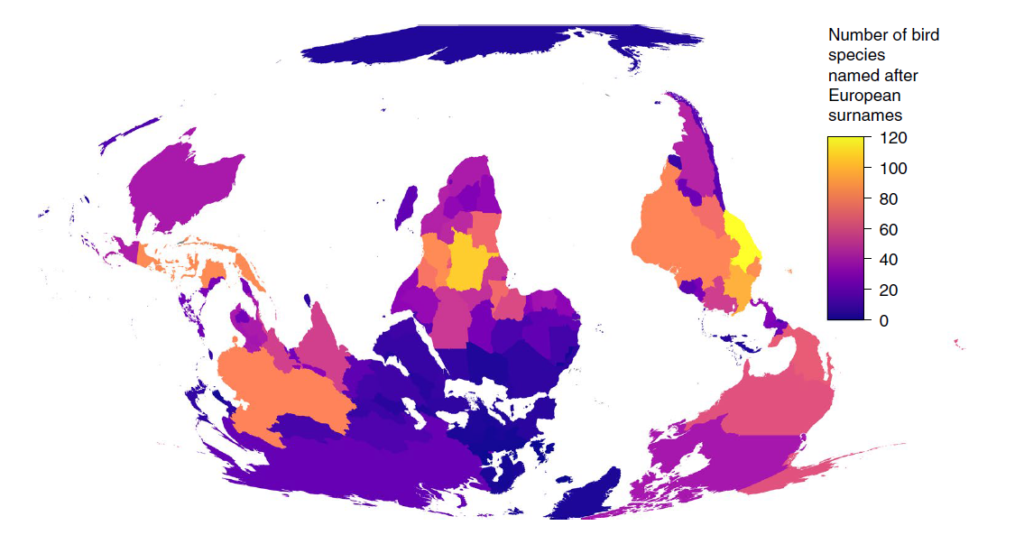

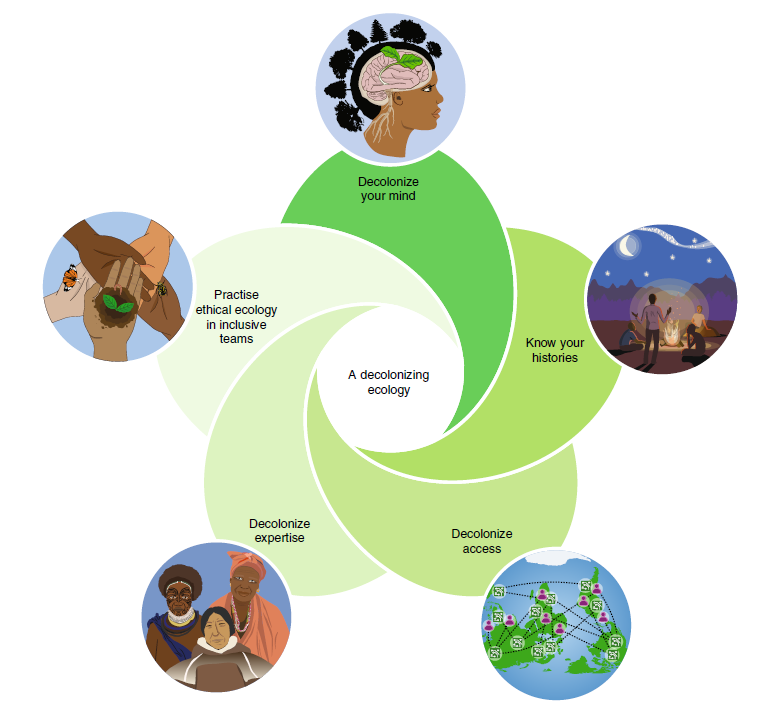

Yet, systems linked to colonial trauma continue to shape the experience of many ecologists, naturalists, biologists, and even anthropologists, today. At the same time, many narratives are still influenced by worldviews that see the advances in the natural or biological realm as carriers of better health, civilization or culture. The consequences of these processes are tangible. A perspective article in Nature Ecology and Evolution8 speaks of colonialism in the mind first, referring to the way a Western scholar might relate to knowledge. From the simple use of language, as when talking about the Neotropical region (new to whom?), or the overwriting of Latin names, sometimes derived from the names of their European discoverers, to the traditional names by which some species are recognized, often more informative about behaviours or characteristics of that species. It could be through devaluating local knowledge, oral traditions, and artefacts that made it possible to navigate an environment in a surprisingly (for us) detailed way, relegating them to folklore or anecdotes, going so far as to claim scientific discoveries, for example, medical properties of plants, already known and shared by local communities for a long time. Fuelling the idea that any active ingredient or species is only really discovered when it enters Western scientific literature, even if they come from a non-systematic and oral knowledge that a population held for centuries.

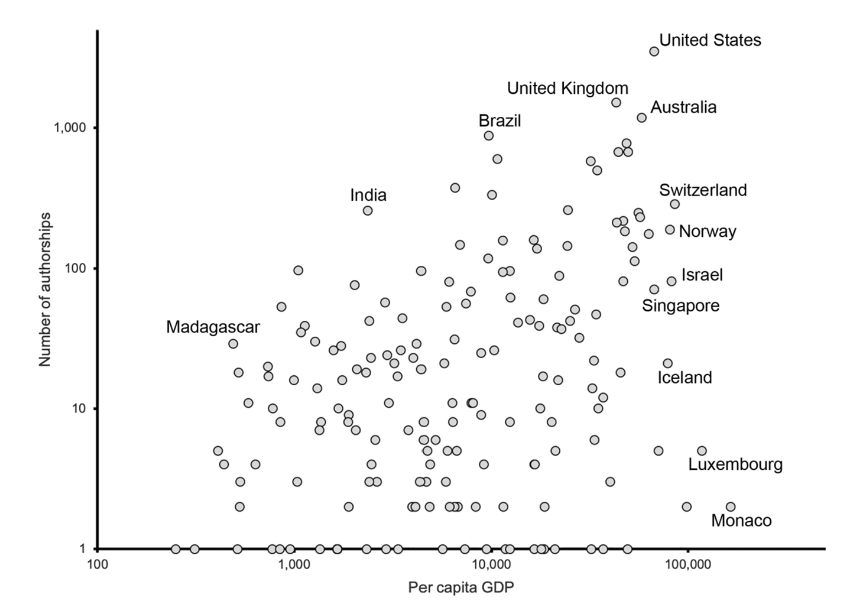

Other than the mindset, inequalities are also visible on a very practical level: the scientific subordination of formerly colonised countries to researchers of the so-called Old World, better known as parachute or helicopter science. The role of local scientists has often been reduced as labourers employed in data analysis and collection for Western scientists. Adding to this, there are the issues with accessing that same knowledge produced in the ‘Global North’, either because samples or data are stored in museums or servers far away from the places they were collected, the absence of high-speed internet, the lack of the right networks, visa issues for accessing conferences9, or simply the high costs of publishing or even accessing scientific literature. Other ways in which parachuting occurs are through drawing on the traditional knowledge of these countries, when this is not belittled, cataloguing and publishing information without mentioning the contribution of local curators and experts.

Another important discussion is about climate change mitigation and rewilding projects when benefits that will be experienced globally demand costs to be felt locally, especially when adequate resources and support are not provided, or when measures impose worldviews external to local values and needs. The same article brings the example of a no-fishing zone established in French Polynesia which was detrimental to local fishermen’s needs, thus ending in simply not being respected and ultimately not helping the conservation efforts on the target fish stock. Top-down management of this kind proved itself to be not only erosive for people’s self-determination but also undermines the very objective of the project.

Many of the difficulties in the field of land management and nature conservation stem right from the relationship with local communities: other risks beyond not considering them (as in the case above), is romanticising them, possibly falling into the Western myth of the good savage, or assuming that indigenous people are willing to do what we ask. Rather, it would be important to recognize that like any human community, the local people we encounter during our work as scientists might have legitimate political, cultural and economic aspirations that could differ from our expectations.

Decolonizing the natural sciences is not a trivial matter. It certainly does not mean throwing away all that has been learned so far and starting afresh, making only use of ancient artefacts and indigenous tales. For many, it is a matter of reflecting critically on their profession, on the political context that allowed the development of each one’s work, on the power structures to which science might have contributed, taking dignity away from some bodies more than others. To “take a stand and recognize ourselves as part of the system we wish to describe, rather than as neutral actors, becoming aware of how backgrounds and training influence the questions that are asked, trying to understand how the data is interpreted and how our work might intersect with the power of companies or extractive interests over a place” 8.

Decolonization would not only be a matter of awareness but also make sure that research methods and implications are not in contrast with local values and management. This would certainly restrict researchers’ access or capacity for action, but it would be an important trade-off for all those who repeatedly had to give up their territories or lifestyles.

Discussions like this are indeed taking root. It happens when researchers use local languages alongside the traditional binomial taxonomic system, or initiatives are taken from established institutions, such as the case of the American Ornithological Society and its statement for changing harmful and exclusionary English bird names thoughtfully and proactively for species10. Or like the Biodiversity Heritage Library, now working to make their materials available in languages other than English11, the Pitt Rivers Museum12 and London’s Natural History Museum13, with their projects aimed at sharing the stories of colonialism behind their collections. More and more resources are becoming available for establishing healthy stewardships with indigenous communities14 or addressing parachute science15,16,17, or simply engaging with diverse experiences from diverse scholars18, 19.

On a side note (but not really), it is also worth mentioning the call for an intersectional approach to these challenges. Noticing how an individual’s capacity to contribute to public and scholarly discourse does not only rely on race/ ethnicity, but similar power dynamics might be in place based on gender, nationality, indigeneity, wealth, spirituality, sexuality, parenthood/dependencies and other identities. “An intersectional approach to practising ecology recognizes the multiple barriers and opportunities facing those working together”8.

These discourses might seem marginal to someone working now on their own seemingly unrelated passion project. Nevertheless, reflecting on how plants, animals, environments, and people intersected and influenced each other in different directions is indeed relevant.

Among all, it is the field of ecology and evolution that explores the relationships between living beings and the environment in which they live. Acknowledging diversity, not only in biological terms but also within systems of knowledge, solutions and stories of the people who are part of it – including their gender, ethnicity and nationality – is certainly a way to widen one’s lens on the world.

I am a visiting researcher at Trinity College Botanic Garden, working on the establishment of its long-term environmental monitoring program and interested in the human dimension of ecological systems dynamics. I wrote this post from the perspective of a western, female, early career researcher, and by no means do I wish to take ownership of the views of those who experience inequity and discrimination on a daily basis, nor do I believe this offers a complete or global understanding of such a complex problem. Rather, I hope to contribute to mainstreaming such an ongoing struggle, thanks also to the encouragement coming from discussing and comparing with peers.

This post is based on an original article I wrote for the Italian organisation Lupo Trek (https://www.lupotrek.it), inspired by reading both academic articles (linked in the text) and outreach pieces such as Deb Roy, R (2018). Decolonise science – time to end another imperial era on The Conversation (https://theconversation.com/decolonise-science-time-to-end-another-imperial-era-89189), Chatterjee, S. (2021). The Long Shadow Of Colonial Science in Noema Magazine (https://www.noemamag.com/the-long-shadow-of-colonial-science/), Boscolo, M. (2018). Decolonizzare la scienza. Il Tascabile (https://www.iltascabile.com/scienze/scienza-colonialismo/), and Wong, J. (Host), (2021, Mar 10). Dirt on our hands: Overcoming botany’s hidden legacy of inequality (No. 7) in the podcast Unearthed – Mysteries from an Unseen World of the Royal Botanic Garden Kew (https://omny.fm/shows/unearthed-mysteries-from-an-unseen-world/dirt-on-our-hands-overcoming-botany-s-hidden-legac).

References

- Olusoga, D. (2020). It is not Hans Sloane who has been erased from history, but his slaves. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/30/it-is-not-hans-sloane-who-has-been-erased-from-history-but-his-slaves

- Stafford, R. A. (2002). Scientist of empire. Sir Roderick Murchison scientific exploration and victorian imperialism, Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 9780521528672. https://www.cambridge.org/ie/academic/subjects/history/history-science-and-technology/scientist-empire-sir-roderick-murchison-scientific-exploration-and-victorian-imperialism.

- Nazia Parveen (2021). Kew Gardens director hits back at claims it is ‘growing woke’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/mar/18/kew-gardens-director-hits-back-at-claims-it-is-growing-woke

- Bathala, D. (2020). Botanic Gardens and Quinine: To Cure or Colonize? Places Journal. https://placesjournal.org/workshop-article/botanic-gardens-and-medicine-to-cure-or-to-consume/

- Anonymous (1900). The Malaria Expedition to West Africa. Science, 11:262, 36-37. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.11.262.36

- Deb Roy, R (2018). Decolonise science – time to end another imperial era. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/decolonise-science-time-to-end-another-imperial-era-89189

- Boscolo, M. (2018). Decolonizzare la scienza. Il Tascabile. https://www.iltascabile.com/scienze/scienza-colonialismo/

- Trisos, C.H., Auerbach, J. & Katti, M. (2021). Decoloniality and anti-oppressive practices for a more ethical ecology. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01460-w

- Martin A. Nuñez (2022), Twitter thread, https://twitter.com/Martin_A_Nunez/status/1559518587127209985?s=20&t=VTOo8e8muypwznf5ldc_Jg

- AOS Leadership (2021), English Bird Names: Working to Get It Right. https://americanornithology.org/english-bird-names/english-bird-names-working-to-get-it-right/

- Ponce De La Vega, L. (2020). Towards Online Decoloniality: Globality and Locality in and Through the BHL. Biodiversity Heritage Library Blog. https://blog.biodiversitylibrary.org/2020/09/towards-online-decoloniality.html

- Pitt Rivers Museum. Critical changes to displays as part of the decolonisation process. https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/critical-changes

- Das, S. & Lowe, M. (2018). Nature Read in Black and White: decolonial approaches to interpreting natural history collections. Journal of Natural Science Collections 6, 4 ‐ 14. https://natsca.org/article/2509

- Indigenous Land & Data Stewards Lab (2022). Understanding roles and positionality in Indigenous science & education. https://www.indigenouslandstewards.org/resource-hub-blogs/understanding-roles-and-positionality-in-indigenous-science-and-education

- Armenteras, D. Guidelines for healthy global scientific collaborations. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 1193–1194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01496-y

- Asase, A., Mzumara-Gawa, T. I., Owino, J. O., Peterson, A. T., & Saupe, E. (2022). Replacing “parachute science” with “global science” in ecology and conservation biology. Conservation Science and Practice, 4( 5), e517. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.517

- Singeo, A., & Ferguson, C. E. (2022). Lessons from Palau to end parachute science in international conservation research. Conservation Biology, 00, e13971. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13971

- Shaw, A.K. Diverse perspectives from diverse scholars are vital for theoretical biology. Theor Ecol 15, 143–146 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-022-00533-1

- Ramírez-Castañeda, V., Westeen, E., Frederick, J., Amini, S., Wait, D., Achmadi, A., Andayani, N., Arida, E., Arifin, U., Bernal, M., Bonaccorso, E., Bonachita Sanguila, M., Brown, R., Che, J., Condori, F., Hartiningtias, D., Hiller, A., Iskandar, D., Jiménez, R., Khelifa, R., Márquez, R., Martínez-Fonseca, J., Parra, J., Peñalba, J., Pinto-García, L., Razafindratsima, O., Ron, S., Souza, S., Supriatna, J., Bowie, R., Cicero, C., McGuire, J. and Tarvin, R. (2022). A set of principles and practical suggestions for equitable fieldwork in biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(34). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122667119