Moderation is the art of “avoidance of extremes in one’s actions, beliefs, or habits”, according to dictionaries. In academic meetings chances are to find a colorful mix of extremes ranging from big mouths to shy introverts, and making everyone’s voice heard can be quite challenging. In worst-case scenarios, even hearing one’s own voice can become problematic.

Moderation is the art of “avoidance of extremes in one’s actions, beliefs, or habits”, according to dictionaries. In academic meetings chances are to find a colorful mix of extremes ranging from big mouths to shy introverts, and making everyone’s voice heard can be quite challenging. In worst-case scenarios, even hearing one’s own voice can become problematic.

In order to make a group discussion productive, smooth and -why not? – fun, participants designate or invite a moderator to fill in the conductor’s role. He or she will have excellent people skills and professional knowledge, will know how to puck the right strings and will seek to achieve group consensus in the most timely and efficient manner. One step ahead of everyone in the group, the moderator will be able to lead the discussion to fertile grounds where every participant is given the opportunity to produce its best.

But there is something more about moderation. A group discussion also resembles a cogwheel: each piece, big and small, make the big machine move. The interesting part however is never the individual piece, no matter how big or small (mouth he or she is), but the whole machine: the final, shiny product ready to roll. These are group synergies produced by the group’s dynamic, which are the most important outcomes of an academic gathering. The essence of moderation therefore revolves around catching and following the group dynamic.

Importantly, just like a good conductor, the moderator should never try playing and conducting in the same time. Even saying it sounds confusing. The moderator has a far more important active job to do than playing. At the end of the meeting, there are one, two or three work objectives that have to be successfully, and thoroughly, met.

Scary as it may sound at first, you might have already pictured yourself in the moderator’s shoes. Question is: are you a natural born moderator? Maybe you already know the answer is yes. Alternatively, perhaps you just need a little more practice, like I do. You don’t know the moderator hiding in yourself until you haven’t tried it.

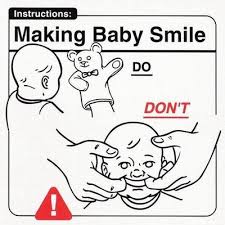

My supervisor asked me to moderate an Ignite Session discussion at the Ecology Society of America 2014 meeting in California. Cautiously, she also suggested I should practice before, by moderating a group discussion about … moderation at a NERD club meeting at TCD. We gathered our ideas about what lies behind a successful moderation and what defines a successful moderator. I listed our thoughts in a cheat sheet below, where I contrast do’s and do not’s of moderation. Having it at hand can help you a great deal preparing for your first, second… however many moderation sessions you will lead.

At the Ignite Session in California, we had a houseful of people, and I only had to use about 5% of my moderator skills. We had questions flowing in for 45 minutes, after which we had to free the room and we moved the discussion closer to a couple of beers. Success! Phew, what an experience! I’m looking forward to the next one.

CLARITY DOs

State the topic, scope, objectives, expectations, rules at the very beginning

Speak up!

Make sure you repeat the audience’s questions so that everyone can hear.

Dig out your best communication skills

Be organized (have introduction, have end summary)

Be rigorous (keep people on track)

Keep it Simple! (simplify, reformulate, translate if necessary)

CLARITY DON’Ts

Ask long questions

Make confusing statements

Get confused and loose track

Get intimidated

PREPARATION DO’S

Have “conversation starters”, a list of questions

Have a global vision of the topic under discussion

Know your audience in advance

Get a hold of the logistics (microphone? assistants? co-moderator? recorder?)

But always be prepared for surprises, good and bad

Practice! Moderate a work group about … moderation!

PREPARATION DON’T’S

Be superficial, unprofessional

Not have a clue about your audience

COMMUNICATION DO’S

Build on previous questions

Ask clarifying questions

Get out of the “rabbit holes” (self-explanatory topics)

Yes, do interrupt “silverbacks” and “prima donnas” (speakers who like hearing themselves)

Have supportive attitude

Calm down spirits

Maneuver spotlights wisely

Make conscious effort to involve each participant to make individual decisions and take independent actions.

Be inspiring

Employ strategies such as group work, “Think, Pair, Share” or “Speed Dating” to engage audience

Redirect people to e.g. Twitter to ask additional clarifying questions

COMMUNICATION DONT’S

Ask closed questions (e.g., to which the answer is obvious)

Shut down speakers

Be cynical

Ask controversial questions that may take days to solve

Have judgmental attitude

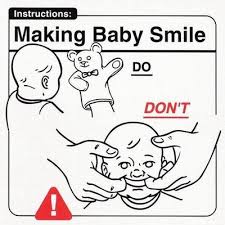

Embarrass & Humiliate

Put people on the spot

Force consensus

NEUTRALITY DO’S

Be neutral, make others debate

Treat everyone equally, make voices be heard

Be respectful

Pay attention to the gender balance

Keep the arguments balanced

NEUTRALITY DONT’S

Take sides

Engage in debates

Answer to provocative questions, argue

Express opinions

Participate in discussions

Share own views

EFFICIENCY DO’S

Be exact & short

Ask the right questions

Focus on the process no matter what

Have an excellent time management

Tackle not more than 3 broad topics

Persevere

Keep discussion alive

Use beeper if necessary to stop a speaker or close a topic and get to the next

EFFICIENCY DONT’S

Chit-chat

Ask meaningless questions

Make the discussion an endless story or soap opera

Ask “pressure mine” questions (put discussion on sidetrack)

Overstuff schedule

FOCUSED DO’S

Pay the highest level of attention

Practice the ability to think two things at the same time (current discussion & next questions)

Be quick witted

Hear everything

Keep track of the discussion

FOCUSED DONT’S

Get distracted, loose track

Get lost in details

Get lost in “rabbit holes” (shallow discussions)

ORGANISATION DO’S

To be able to synthesize, take notes along

Summarize periodically (at least provide a mid-summary)

Provide end summary

ORGANISATION DONT’S

Let the discussion flow endlessly

Loose audience

Loose end and scope

PERSONALITY DO’S

Be dynamic (follow the group dynamic)

Be flexible (do not stick to your pre-prepared questions)

Be creative!

Use your sense of humor

Be confident!

Be engaging!

PERSONALITY DONT’S

Be melancholic and sad

Be tired and depressed

Be bored

Be narrow-minded

Be rigid

Remember:

- Moderation is an art, you need to use both people skills and professional knowledge.

- The success of a discussion depends on how well prepared and competent you as a moderator are.

- It is a very good idea to follow the group dynamic and obtain group synergies.

Author: Ana Maria Csergo, csergoa[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: Safe Baby Handling Tips

So, it’s that time of year again; as the cold, damp, dark, weather sets in we look to warmer climes for escape and entertainment. So; Take 26 people, from all walks of life, throw them together in a tropical paradise to camp with bugs, beasts and cold-water showers for 10 days and watch the dynamics and lessons unfold….

So, it’s that time of year again; as the cold, damp, dark, weather sets in we look to warmer climes for escape and entertainment. So; Take 26 people, from all walks of life, throw them together in a tropical paradise to camp with bugs, beasts and cold-water showers for 10 days and watch the dynamics and lessons unfold….