Before I moved to New Zealand birds were, well, birds. They were nice to see but I didn’t pay them much attention. But New Zealand is a bird paradise and as a biology student (I studied for my undergraduate degree at the University of Auckland) birds were the go-to exemplar of many biological concepts. With understanding often comes interest and I found myself increasingly interested in our avian friends, an interest which has stayed with me to this day. Continue reading “Kapapo, Kereru and Kaka, Oh My!”

Presentation tips: how to create and deliver an effective talk

Off the back of our recent Postgraduate Symposium, I thought it would be useful to summarise some of the advice and criticism we received afterwards. These points are a mix of the feedback from our invited speakers, academic staff and fellow postgraduate students, as well as some of my own observations and preferences. While the majority of the information below is common knowledge and most people do their best to give a good talk, the reality is that there is no such thing as a perfect talk and there will always be room for improvement; that’s fine! Just do your best and afterwards take note of what areas you would like to improve.

1) Remember: slides are an aid to your talk, they are not the focus. Your voice should be the primary focus of the audience; the accompanying slides are to help you explain more complicated ideas and results, introduce a study system or area and generally keep your audience interested (hence the inclusion of many an interesting/pretty/grotesque picture). Therefore, in general, you do not need large sections of text on your slides. As much as you may think the text is necessary, it most likely isn’t so get rid of it! This removes any temptation to read off the slides and helps keep your audience focussed on you. Furthermore, you are more likely to give a better talk with a more natural flow if you stick to this. The most informative and enjoyable talks I have seen typically contain slides with almost no text, primarily using figures, photos, cartoons etc. Also, don’t go for overkill and try to say too much. Present a concise, clear and fluid story for your audience to follow, leaving out any gritty methodological and statistical details that are not central to your research.

2) Talk to the audience – all of it – and never to your slides. This means that you always face your audience, regularly changing the direction of your gaze, speaking loudly, slowly and clearly, therefore engaging as much of the audience as possible. Furthermore, when you are presenting to an international audience, remember that English (or whatever language you are speaking) may not be the first language of many attendees. This is when it is even more important to make an effort to speak loudly, clearly and slowly (and avoid using any slang).

3) Enjoy yourself! Do your best to smile, relax and be enthusiastic about your research. Unlike a typical manuscript, a presentation allows you to inject some passion for your work. If you are not engaged or enthused, how do you expect your audience to be?

4) Always remember to state the general importance of your research and what areas it applies to. Make your research and topic as relevant to as many people as possible (within sensible limits, of course). This is sadly overlooked by many postgraduate students and can be frustrating to watch. You can do this (i) at the beginning by starting with a broad introduction (this does not equate to five slides of background information, rather it could simply be a few sentences, just to provide your audience with a context) and (ii) at the very end, discussing the implications of your results to your field as a whole, addressing the scope of the symposium/conference/session if particularly appropriate.

5) If a particular aspect of your work is complex and difficult to explain, do your best to deconstruct it with the relevant figures and always repeat the main point/finding before proceeding.

6) Always handle questions in a polite, interested and engaging way. Be open, not defensive. A good tip is to repeat each question for the audience so that they all hear it. While this keeps all of the audience clued in, it also gives you time to formulate a response in your head. When you respond, remember to address all of the audience, not only the ‘questioner’, and always mention that you’re happy to discuss things further afterwards (I’d go as far as encouraging people to come chat to me afterwards, even if it is just to grill me; a grilling is always welcome as a postgrad!).

7) Dress for the occasion. Be comfortable but also mindful of why you are giving a talk and who you are giving it to.

8) If you are using a laser-pointer, avoid waving it around excessively on the screen. Use it sparingly, only when a particular detail needs highlighting.

9) Always check the compatibility of your files, allowing time to make amendments if needed, save in multiple formats and have back-ups, whether on another storage device or in your email inbox.

10) Learn from other presentations what aspects you particularly like and dislike. For example, I prefer when acknowledgements come at the start of start of a talk as this allows the speaker to finish with a focussed, ‘take-home’ message of the research. Also, you don’t need to read out every name in your acknowledgements; people will always do it themselves so just go for the major ones.

11) Practice your talk multiple times aloud (how it sounds inside your head does not equate to how it actually comes out).

12) Finally, don’t panic; be confident and do your best.

Author: Seán Kelly, kellys17[at]tcd.ie, @seankelly999

Image Source: phdcomics.com

Pity the Poor Pangolin

The pangolin is one of those lesser-known animals, at least in the West, most commonly seen as slightly dusty museum specimens (there’s one in our own zoology museum). Yet across their native lands they’re well known and very popular. Unfortunately this popularity is as food and traditional medicine. Indeed, recently the IUCN released a report saying, of the Chinese pangolin, “they are more than likely the most traded wild mammals globally”. This statement came following the first international conference on the conservation of pangolins, held by the IUCN. There is a very real fear that the Chinese pangolin and its relatives will be eaten to extinction.

I first became aware of the plight of the pangolin when I saw an article last year. A ship had run aground in a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Philippines (violating several laws in the process). When the ship was rescued it was found to contain 400 boxes of frozen pangolins, totalling 2,000 animals. All illegally caught, shipped and intended for trade on the black market. In searching for the news report I saw all that time ago I discovered that this was a remarkably common occurrence with illegal shipments being so widespread as to be almost mundane.

I first became aware of the plight of the pangolin when I saw an article last year. A ship had run aground in a UNESCO World Heritage site in the Philippines (violating several laws in the process). When the ship was rescued it was found to contain 400 boxes of frozen pangolins, totalling 2,000 animals. All illegally caught, shipped and intended for trade on the black market. In searching for the news report I saw all that time ago I discovered that this was a remarkably common occurrence with illegal shipments being so widespread as to be almost mundane.

So what is a pangolin and why are they in such high demand? The pangolin is a generic name for eight species of the genus Manis. The name comes from the Malay word pengguling which means “roller”, a nod to one of its key features: that of its ability to roll into a ball when threatened. Its alternative name, scaly anteater, acknowledges its other major features: the large scales that cover its body and its similarity in appearance and diet to the anteater. They are solitary, nocturnal and secretive creatures, found across Asia and Africa. Four species are found in Asia: the Indian pangolin (M. crassicaudata), the Chinese pangolin (M. pentadactyla), the Malayan pangolin (M. javanica) and the Philippine pangolin (M. culionensis) and four species are found in Africa: the cape pangolin (M. temmincki), the tree pangolin (M. tricuspis), the giant ground pangolin (M. gigantea) and the long-tailed pangolin (M. tetradactyla).

They are insectivorous, preferring ants and termites but branching out to other invertebrates, such as worms and crickets, when the mood or circumstances take them. Some are arboreal while others live mostly on the ground. They are sexually dimorphic with males being larger than females. Males have larger territories than females and their territories often cross, resulting in meetings that may lead to matings when the female is in oestrus. A single offspring is usually born and is carried by the mother on her tail for about 3 months until it is weaned. It stays with her for a further two months before leaving to find its own territory. It is not known how long pangolins live in the wild, though they have survived for 20 years in captivity.

They are insectivorous, preferring ants and termites but branching out to other invertebrates, such as worms and crickets, when the mood or circumstances take them. Some are arboreal while others live mostly on the ground. They are sexually dimorphic with males being larger than females. Males have larger territories than females and their territories often cross, resulting in meetings that may lead to matings when the female is in oestrus. A single offspring is usually born and is carried by the mother on her tail for about 3 months until it is weaned. It stays with her for a further two months before leaving to find its own territory. It is not known how long pangolins live in the wild, though they have survived for 20 years in captivity.

Pangolins do not, to my eyes at least, look particularly appetising, but there is clearly a demand for them. The best estimates are that between 91,000 and 183,000 were traded in the years 2011 to 2013. For an animal with a low reproductive rate this level of hunting is clearly unsustainable. And all this trade is illegal under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species). The demand is such that people are willing to risk prosecution and imprisonment. But what is driving this demand?

Unfortunately, it seems to be that much of the trade in pangolins is driven by the fact that eating them is seen as something of a status symbol. As they become rarer the prices go up, and this only adds to the appeal. An article from last year said that a restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City sold pangolins for between $600 and $700! Doing some ‘back of a napkin’ sums, this is about 3 months average wage in Vietnam, or the equivalent of spending about €10,000 on a main course in Ireland. There is no food that could be so tasty as to be worth that much. This is not about the quality of the food but the experience of being able to say to your friends “I have so much money I was able to eat pangolin last night”. I wouldn’t be surprised if it turned out that pangolin actually tasted pretty disgusting (I almost hope it does!).

The other use for pangolins is in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Ignoring the fact that “traditional” Chinese medicine was invented by Mao in the 1950s, pangolin scales are keratin, the same stuff that makes up your hair and nails. Yet still hundreds of kilos of scales enter the black market as they are said to be associated with the “liver and stomach channels” and treat a range of conditions mostly involving blood and pus.

The solution to the black market trade in pangolins is not easy. The rarer it gets the more valuable it becomes, both in itself and as a status symbol. I don’t know how you go about changing that attitude. Given that it seems to be considered an aphrodisiac in some regions, there is a lot of cultural baggage surrounding this poor creature. How do you try and convince people that eating pangolins will not increase your virility or that eating their scales will not improve your blood circulation? The easy answer is ‘education’ but this is only part of the solution because I doubt that many of the people eating pangolin really do so as an expensive form of Viagra, they do it because it’s an easy way to show they have money and that is a much harder cultural attitude to change.

The solution to the black market trade in pangolins is not easy. The rarer it gets the more valuable it becomes, both in itself and as a status symbol. I don’t know how you go about changing that attitude. Given that it seems to be considered an aphrodisiac in some regions, there is a lot of cultural baggage surrounding this poor creature. How do you try and convince people that eating pangolins will not increase your virility or that eating their scales will not improve your blood circulation? The easy answer is ‘education’ but this is only part of the solution because I doubt that many of the people eating pangolin really do so as an expensive form of Viagra, they do it because it’s an easy way to show they have money and that is a much harder cultural attitude to change.

So, pity the poor pangolin. Ignored in the West, revered in the East: as food, aphrodisiac, and alternative to chewing your nails.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image Sources:

Wikicommons

Scale image from http://bit.ly/1m7QGGW courtesy of TRAFFIC.

The Great Escapes

I was looking through some of my photos from volunteering in Namibia which reminded me of Houdini, the incorrigible baboon, who, no matter the precautions and security, would frequently turn up inside one of the guest’s houses rifling through their suitcases. This made me think it’d be fun to have a look at some of the most dangerous, daring and seemingly impossible animal escapes from zoos and aquariums over the years.

So many stories came up but these are my favourites:

Fu Manchu

This orangutan, a former resident of the Omaha zoo in the 1960s, was very often found peacefully reclining in the trees outside of his enclosure when his keepers arrived for work. Every door was locked and left intact so it took a long time, and a lot of threats of staff being fired, for them to catch him in the act. In the end it was a combination of stealth and CCTV that did it in for poor old Fu Manchu. He was observed, long after the zoo had closed and keepers gone home, climbing into one of the air vents and moving along the dry moat surrounding the enclosure until he reached a connecting furnace door. Here he managed to use his great strength to prise the door open just enough of slip a piece of wire through and pick the lock. Where he learned to pick locks nobody knew, but what also puzzled his keepers was that for the following days nobody could find the wire he had used and it wasn’t in the door. It wasn’t until some time later that one of his keepers noticed something sticking out of his mouth while he was eating; turns out he had been keeping the wire hidden and safe inside his cheek during the day!

Nikica the hippo

There have been a few stories of lost and escaped parrots and parakeets turning up in peoples’ back gardens- but what about a hippo!? That’s just what the people of Plavnica, Montenegro face every time there is a flood. The only thing is that it is always the same hippo: Nikica. The zoo is situated on the border with Albania and the region suffers frequent rises in water levels allowing Niikica to float seamlessly over her fence and out to explore the village. The best part of this story is the attitude of the people: everyone appears very relaxed at the idea of this two-tonne lady ambling around the village until the water gets back to a reasonable level. She even gets the VIP treatment at a local restaurant where she turns up for bread and a dip in their pool! Not so much an escape as a regular holiday.

Pacific octopus:

Octopuses are renowned for their ability to squeeze through a tight spot and contort their bodies into almost impossible shapes and positions to reach their destination. This makes them master escape artists. Indeed their stories have become the stuff of legend in aquariums (and some myths too). One story though that caught my attention simply because of the scale was that of pacific octopuses (which can reach an average length of 15-20ft) in the Steinhardt aquarium in San Francisco. The octopuses regularly found ways of sneaking along the drains from their tanks into neighbouring tanks to feast on the tasty crabs for a midnight snack. As one attempt to foil their escapes, the keepers put layers of Astroturf above the waterline in these tanks. Octopuses don’t like Astroturf as their tentacles can’t get good suction. The pacific octopuses however managed to find a way around these barriers and, on one occasion, a night watchman found the forty-pound octopus in the middle of the aquarium floor at 2.30AM!

Chuva the macaw:

One sunny afternoon at Vancouver zoo, the keepers decided to let the parrots out for a stroll on the grassy patches near the front of the zoo. The area was fenced and the birds had had their wings clipped so there wasn’t much danger of them straying far. Even when it was discovered that one of the macaws was missing, there wasn’t too much concern, as the birds can’t exactly run fast. The hours passed however and still no sign of Chuva. That is until a phone call was received from a group of bewildered visitors over 30miles away who had discovered a stow-away in their RV. It seems Chuva had managed to get through the fence and out into the parking lot where she spied the open door of the RV and hopped board for some AC, some fruit and the feel of the road!

Butch and Sundance- The Tamworth Two

No story of escape would be complete for me without the famous pigs of 1998. Butch and Sundance were five month-old brother and sister Tamworth pigs that escaped form an abattoir while being unloaded from the lorry. They squeezed through a fence and swam across the River into nearby gardens. The pair was on the run for over a week, hiding in the dense thicket and entertaining local media and families. Their antics caused such a stir that, even though their owner still intended them for slaughter, they were purchased by the Daily Mail newspaper! They were eventually rounded up, Butch one day before Sundance, and sent to live out their days at the Rare Breeds Centre in Kent. Butch died at the ripe old age of 13 in 2010 and Sundance at 14 in 2011.

Author: Deirdre McClean, mccleadm[at]tcd.ie, @deirdremcclean1

Image Sources: BBC, Reuters, Wikimedia commons

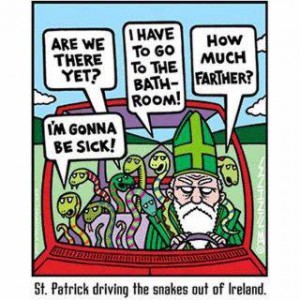

Island of Saints and Snakes?

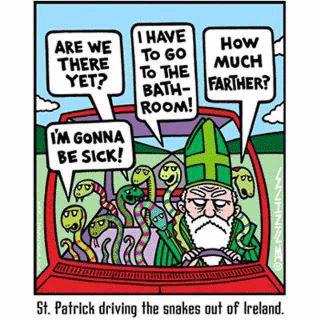

Pubs, parades, shamrocks and snakes – an interesting mix of descriptors for any national holiday. Our patron saint of cultural identity (i.e. unashamed marketing of the Irish brand) was an affable fellow who, along with a historically proven love of Guinness and marching bands, is attributed with ridding our shores of serpentine beings. However, we give him more credit than he deserves.

As far as we know, Ireland never had any snakes. The reptiles couldn’t have survived during the last Ice Age. When the big freeze ended around 10,000 years ago it seems that snakes didn’t manage to beat the rising seas to get to the Emerald Isle. Ireland was cut off from Britain about 2,000 years before Britain was severed from mainland Europe. Three snake species colonised Britain but they never made the journey across the Irish Sea. But why not? It’s not that Ireland’s famously “balmy” weather was inherently inhospitable to reptiles. The common lizard managed to get here, seemingly in the post-Ice Age, pre-Irish Sea window that could have been open to snakes as well. To paraphrase sporting victories of the weekend, among reptiles it seems that lizards but not snakes were able to answer Ireland’s call…

Patrick didn’t drive the snakes into the sea but there’s a popular belief that this story is symbolic for how he rid of Ireland of pagan Druids. It’s attractively biblical in the telling; Christian missionary triumphs over snake-worshipping pagans. But there are a few problems with the story. For one thing, if there were never any snakes in Ireland then how could they have been used as symbols by Irish druids? Some writers suggest the prominence of snakes in Irish Celtic spirituality was a holdover from the Celts’ British/European ancestors who would have experience of the animals. Similarly, trade interactions could have brought stories of snakes from abroad.

Did Patrick banish the pagan Druids who were symbolised by animals that they had heard of but probably never seen? Nope. For one thing the story of banishing snakes; real or symbolic, was only attributed to the saint centuries after his death. Patrick was neither the first nor last in a string of missionaries to bring Christianity to Ireland. Furthermore, he neither banished the Druids nor cleansed Ireland of paganism and the final Christianisation of Ireland didn’t take place until at least the 14th century (a trend which we seem to be reversing now).

So Patrick didn’t banish snakes, Druids or paganism. Rather than ecological manager or societal revolutionary, arguably his main legacy is as the excuse for a day to paint the world green (or should that be blue…)

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: reddit.com

What’s it like to study Zoology?

Tell someone on the street that you study Zoology and you can pretty much guarantee what their follow up question will be; “so you want to work in the zoo?” Well not quite. Of course some zoology graduates conform to the general stereotypes; the zookeepers, conservation managers and wildlife handlers who keep the rest of us supplied with a steady stream of tales of adventurous exploits and envy-inducing pictures on Facebook. But that is only one side of what you can do as a zoologist. It’s not all about frolicking with cute animals. There’s a healthy dose of molecular and lab-based research, theoretical studies and unavoidable number crunching which make up significant portions of life as a zoologist. Not to mention the diverse career opportunities, in areas such as science communication, education, policy and management, that are available to zoologists who venture beyond traditional research jobs.

A group of Transition Year students (15/16 year olds) recently spent a week in the department learning about what it’s like to study and work as a zoologist. Some of their questions and misconceptions prompted me to write this blog. Consider it the lowdown on zoological life if you will.

Zoology is not just about cute animals

If your interest in zoology stems from a desire to spend your days playing with puppies or equivalent bundles of cuteness then be warned. Such opportunities do arise during a degree course but they are relatively limited. You will spend more time in lecture rooms, dissecting dead animals or behind a computer than you will interacting with live animals. Of course field courses, summer research opportunities and final year undergraduate projects do offer many opportunities for hands-on, practical experience but these are the exceptions rather than the rule for life as an undergraduate zoologist. Post-graduation is another story entirely: there’s puppies, meerkats, elephants and dolphins aplenty if that’s what you want!

Zoology is not stamp collecting

Modern zoology stems from the long scientific traditions of enthusiastic naturalists: the genteel country gentlemen who wiled away the hours with contemplations of beetles and the exotic explorers who bravely ventured forth into unknown lands. These origins have created a common misconception that modern zoology follows the same veins; we may collect DNA sequences rather than butterflies now but surely it’s all just descriptive stamp-collecting at heart? Well, no. The methods and techniques used in zoology research are just as scientifically rigorous and complex as the “machines that go ping” which grace any physics or chemistry lab. Zoology is no more exempt from number crunching and computational methods than any other scientific discipline. You don’t have to be a maths whizz or computer nerd but a career in zoology, no matter what branch, will inevitably involve quantitative and not just qualitative analyses.

(Most) Zoologists are not hippy dippy animal lovers

A common misconception about being a zoologist is that it’s a just a fancier term for people who are only concerned with animal rights and issues. So we should all be strict vegans who spend our holidays trying to board Japanese whaling ships and we would rather halt economic progress than lose a single species of ant to extinction. Inevitably there is an element of truth to these ideas. We chose to study zoology because we’re fascinated by the natural world and the logical progression of such interests is a desire to protect and conserve all aspects of life on our planet. But our pro-animal tendencies don’t equate to making us anti-human! Zoology teaches us to develop and apply appropriate, practical and realistic management and conservation actions to protect biodiversity while also enhancing human economic and social livelihoods.

Zoologists don’t just do field work

I chose to study science generally and zoology more specifically because I was adamant that I didn’t want to be stuck at a desk in an office. Guess where I spend most of my days now? Zoology isn’t all about trekking through jungles or diving on ocean reefs. Most research zoologists spend the majority of their time indoors whether that’s at the lab bench or behind a desk. The difference lies in the fact that, unlike a “normal” desk job, zoology provides plenty of opportunities to get out of the office whether that’s catching vultures in Swaziland, perusing museum collections, island hopping in Indonesia or traveling the world for conferences. These are the undoubted highlights of any research project but they represent the cream of zoological life: usually you will spend far more time working at your computer than exploring the outside world.

Zoology is…great!

Don’t be fooled by the apparent negativity of the points above. I love studying zoology. I love the diversity of the subject, the breadth of knowledge to which we are exposed, the fascinating research questions we study and our undeniably awesome opportunities to travel. I fell into zoology by accident rather than design and I could not be happier with my choice of subject. Research careers in zoology are varied and exciting but a zoology degree is also great preparation for so many opportunities beyond the realms of traditional research. Zoology is suited to people who are interested in nature, the environment, biology in general or anyone who is a confirmed lifelong disciple of Sir David. Zoologists are well equipped to take up any variety of career paths.

Our horizons both include and extend beyond the zoo gates!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: Wikicommons

Rewilding

Rewilding is the mass restoration of ecosystems by reintroducing (often long) lost animal and plant species which are then left to develop without human interference. It’s a topic explored by journalist George Monbiot in his latest book, Feral [1]. Monbiot captures the controversy surrounding rewilding with typical understatement, “Reintroducing elephants to Europe would first require a certain amount of public persuasion.” And “The clamour for the lion’s reintroduction to Britain, has, so far, been muted.” So why should we do it? He argues, and I agree, that people would value a biologically rich world over the desolate sheep-scapes that are common to the UK and Ireland. We live in a shadow world where we can see evidence of species that once surrounded us. One of the more striking examples of this shadow world are the putative elephant-resistant adaptations seen in Temperate trees. So, over and above the ecosystem services that would be realised and the potential financial gains resulting from such an endeavour, the primary motivation here is to nurture the existence value we draw from biodiversity.

The wolf reintroduction to Yellowstone is a great example of a successful reintroduction whose effect was felt throughout the trophic web. The wolves created zones of fear, areas where their prey no longer dared to venture which allowed vegetation to reestablish. This, in turn, gave habitat for animals like beavers to occupy. This in turn had a massive knock-on effect on the entire ecosystem and the other habitats of the park, all of which illustrates the profound influence predatory megafauna can have and the disastrous and unrectifiable trophic cascade which can occur where they are excluded.

Naturally, there are some serious obstacles to advancing this goal. It’s not a simple matter of dumping a pride of lions into the woods and hoping for the best. There will have to be some priming of the area if we want the animals to flourish. The Irish countryside isn’t as well suited to wolf packs as Yellowstone. This is especially the case if Pleistocene rewilding is taken seriously. Monbiot explains, “People who call themselves Pleistocene rewilders seek to recapitulate the prehuman fauna of the Americas.” This could be achieved through DeExtinction of long-lost species or by reintroducing proxies which would serve the function of the missing animals or plants. In the US where there are extensive wildlife areas that we Europeans could only dream about, reintroducing long disappeared animals or proxies doesn’t seem quite so ridiculous. For us, with so little unmodified habitat it almost seems like a non-argument when we don’t even have mundane megafauna or any land on which to put them. To take one example, the African species of cheetah could fill in for the American species (Miracinonyx), preying on the fleet-footed pronghorn, whose speed is another instance of an adaptation to a long-lost predator. But the issue here is the time that has elapsed since these species went extinct. Perhaps the ecosystem has changed too much for the species, proxy or not, to settle back in. Modern day North America is a very different place to the one of 12,000 years ago.

There is ample opportunity and, more importantly, land, to proceed with rewilding plans outside of traditional protected areas. Agricultural property is being abandoned all over Europe and North America as people move to cities. Rather than keep it fallow, why not restore the landscape to something of value?

This would represent an excellent opportunity for scientists and policy makers to engage with the public and highlight the benefits of rewilding or at least get it into the public consciousness. Of course there will be detractors, but the arguments for could be framed in such a way as to convince most reasonable people that wolves won’t be stalking their estates. I think rewilding is an exciting way to develop conservation; it is dynamic which is in contrast to the passive, ‘protect what we’ve got’ ethos, common to conservancy. It also brings some much needed positivity, opposed to the negative, guilt-laden, reactionary aspect of much of nature conservation.

Authors: Adam Kane: kanead[at]tcd.ie, @P1zPalu

John Kirwan, @JohnDKirwan

References

1. Monbiot, G., Feral: searching for enchantment on the frontiers of rewilding. Allen Lane, London, 2013.

Image Source: Wikicommons

How to write press releases

Consider this scenario. You’ve recently published a new academic paper. It’s effectively your baby. The months or years of experiments, analysis, frustration, toil and troubles are now distilled into a stellar research article which, in your opinion at least, changes the face of science as we know it. Great! Now you need to get the word out beyond the Ivory Tower of academia and journal articles. Time to brush up on your public relations and communications skills.

Press releases are important tools for communicating scientific findings and informing the public about the importance of scientific research. From a researcher’s point of view they are also essential currency for enhancing your research profile and ticking the public outreach box on your next grant proposal. So, from all perspectives, it’s important to get press releases right.

We had an excellent NERD club session recently with Thomas Deane, press officer for the faculty of engineering, maths and science at TCD. His tips sparked a great group discussion about the dos and don’ts of writing good, interesting and hopefully popular press releases. Here are some of his useful guidelines which will come in handy next time you’re faced with writing a press release.

1) Simplify!

Remember that you’re writing for a non-specialist audience. Simplify your message as much as possible. Keep cutting things out of the article until it’s clear and succinct. Eliminate jargon but if you do need to use a particular specialised term then make sure that it’s explained properly.

2) Focus on the key parts

You already had to condense your months or years of work into a single paper. Now you need to do it again for the press release. Choose one or two of the key findings from the paper and explain them clearly and concisely. If possible ask someone without a science background to read your article. If they can understand it and identify importance of the findings that you’re trying to publicise then it’s a good indication that you’re on the right track.

3) Be active!

For reasons best known to the Department of Education, in school I was taught that you should only ever write about scientific research in a passive voice; “the animal was weighed” rather than “I weighed the animal”. This early training was reversed when I reached college but there are still some researchers who are stuck in their passive ways. Don’t fall into the trap! Writing in the active voice is easier to read, more interesting and will save on your word count. Press releases should be clear and engaging – this is infinitely easier to achieve if you write in the first person, active voice.

4) Find useful analogies

Good analogies should be engaging and clear. They’re particularly useful for attracting the attention of your audience and for explaining complex ideas. It’s a fun and beneficial exercise to come with an analogy to describe your own research. Here’s some of ours; territoriality behaviour in badgers is like the fall of the Berlin wall (they don’t respect boundaries) and ecosystem stability is like a Jenga tower (remove some key pieces and the whole ecosystem collapses).

5) Focus on the big picture

Research is inevitably piecemeal. Instead of the big bathtub Eureka moments, most new scientific findings represent small steps of progress in niche research areas. However, every tiny step contributes to an overall bigger picture. When communicating the importance of your work to the media it’s important to frame your research in a wider context. Think about why your research matters, where it could lead and why people should find it interesting. Remember that journalists and editors are short on time and probably patience. Your press release needs to include clear reasons why your work is interesting and deserving of their attention. However, one caveat to remember is that you shouldn’t artificially over-inflate the importance of your research. Don’t claim that your new findings about Drosophila are going to save polar bears from climate change!

6) Include quotes and images

A good press release is a sales pitch. You need to excite and enthuse people about your research. Striking, unusual pictures and engaging, personal quotes will help to sell your message. If you include direct quotes and captivating pictures with your press release then it’s more likely to attract the interest of the journalists and editors who take up the story. To supplement printed quotes it’s a good idea to give your contact details and state that you’re available for interviews. The media success of Kevin Healy and Andrew Jacksons’ paper about time perception in animals last year is testimony to the benefits of good images and engaging interviews for selling a story (even if people add images which slightly misrepresent the paper!)

If you keep these considerations in mind they will undoubtedly improve your skills when it comes to putting together your next press release.

Go forth science communicators!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: myteltek.com

Gould Mine

The career of Stephen Jay Gould eludes easy definition because of his prolific output in so many areas. Michael Shermer characterises him as a historian of science and scientific historian, popular scientist and scientific populariser.

The popular science writings of Stephen Jay Gould (20 of his 22 books and hundreds of articles) are responsible for making me want to study macroevolution. He said of his popular essays that they were intended “for professionals and lay readers alike”. We have already covered some aspects of science communication, like how to do it and which kind of scientists should engage in it. Gould wrote 479 academic papers during his career, so any thought of public outreach damaging one’s science certainly didn’t apply to him.

Let’s have a closer look at his academic legacy. Gould is well known for his theory of punctuated equilibrium co-written with Niles Eldredge. This fuelled the debate around ideas such as species selection and the mechanisms explaining macroevolutionary patterns.

Despite this being the work for which he is best remembered it represents a tiny fraction of his output. He actually published only 15 papers with this theory as a main topic, which represents only 3% of his academic work! As a comparison, he published more papers (17) on baseball!

His primary field was invertebrate palaeontology (he was the curator of Harvard’s Invertebrate palaeontology collections from 1973 to his death in 2002) but again, even his main focus in this area (on Cerion snails) represents only on one quarter of his work. Shermer describes him as being “no single-minded fossil digger or armchair theorizer.”

Actually, nearly one fifth of his massive scientific output is primarily focused on the history of science. Again, as Shermer says, he was a “Historian of Science and Scientific historian”.

So Gould should not be only remembered for his proposal of punctuated equilibrium. Gould published 169 papers in 23 last years of last century, which gives him an average number of publications in the history of science of 7.34 per year. To put it in the historical context of the field, the only names that have been more productive are Aristotle, Kant, Goethe and Newton.

It’s rare to see a scientist who divided opinion so much, hagiographies have been written about him but he’s also loathed. Look at these for contrasting views:

“In the field of evolutionary biology at large, Gould’s reputation is mud.”

“Steve is extremely bright, inventive. He thoroughly understands paleontology; he thoroughly understands evolutionary biology.”

I’ll leave it to the reader to find out where they stand on Gould for there is a lot of controversy to consume. I prefer to remember him through his essays on Natural History than through his few papers about punctuated equilibrium, better illustrating the “measure of a man” (that’s Shermer’s pun). His life illustrates how interdisciplinary studies exponentially increase scientific productivity: “Gould has used the history of science to reinforce his evolutionary theory (and vice versa)” writes Shermer. And that applies as much to punctuated equilibrium as to baseball!

Authors: Thomas Guillerme (guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme) and Adam Kane (kanead[at]tcd.ie,@P1zPalu)

Image Source: Wikicommons

Killing in the Name of Science – Dying for Conservation

Conservation. Noun. From the Latin verb conservare, to protect from harm or destruction.

Dallas safari club auctions off permit to hunt rare rhino.

Giraffe unsuitable for breeding killed at Copenhagen zoo .

Six Lions at Longleat safari park destroyed due to excessive population increases.

What on earth is going on?

These stories have gone around the world and caused almost unanimous outrage. This is not surprising. The disparity between the ideals of conservation and the sometimes tricky real-world dilemmas that occur can cause consternation and indignation to many. Given my previous posts you won’t be surprised to learn that it might be a bit more complicated that the headlines have led us to believe. So let’s delve a bit deeper and see whether these animals were justifiably killed or whether there’s something else going on. As always, I’m going to try and leave the ethical considerations to one side as much as possible and focus on analysing the scientific justifications given. So, on with the show . . .

The Rhino

In early January a permit to shoot an elderly rhino was auctioned off to raise money for rhino conservation. There are arguments on both sides as to whether this was a good idea. The rhino was, according to reports, an old, non-breeding male rhino who had the potential to injure or even kill younger males. Removing him as a threat seems to be a good idea. Culling occurs in many managed populations and is used to maintain healthy, sustainable populations. Removing this animal from the population is, based on our understanding of male rhino dynamics, the best course of action scientifically.

Whether the auction was the best way of achieving this is outside my remit. Culls can, and do, occur with less publicity and spectacle. Given the outrage expressed, it would be interesting to know how many of the people complaining had ever donated to rhino conservation organisations. If the organisations were not so desperate for money would they have ever considered such a headline-grabbing action?

The Giraffe

Copenhagen zoo killed a giraffe that was considered useless for breeding . They then publicly dissected it and fed it to their lions. This story is the most interesting as it has two separate components: the killing and the treatment of the animals after death. Here I am extremely split. Captive giraffes are, to some extent, victims of their own success. Breeding programmes across Europe have been very successful and zoos are pretty much at ‘carrying capacity’ with few able to take excess giraffes and genetic inbreeding is becoming a problem. One of the zoos that offered to take the giraffe already has his older brother which was the argument used against the transfer.

The obvious solution would be to prevent the giraffes from breeding in the first place but this isn’t always easy in giraffes. From the BBC article,

“Contraception and castration have been raised as possibilities, but both would require sedation. This is a relatively high-risk procedure in the case of giraffes, as they are liable to break their necks when they fall while sedated.”

There are contraceptives available now that can be used with little risk so the number of ‘excess’ giraffes should reduce in the future. However, Copenhagen Zoo has a policy of allowing their animals to breed naturally, even though this is clearly causing a surfeit of animals.

As to the treatment of the body, I’m in no doubt they did the right thing. One of my favourite TV programmes in recent years was Inside Nature’s Giants where large animals were dissected and their anatomy and evolution was described and shown in all it’s ‘gory’ detail. I am all for increasing the public understanding of how animals work and the crowds that gathered to watch are proof that this interest exists. It is important to demystify biology and this is a great way of doing so. As for feeding the giraffe to the lions, well, what else were they going to do with it? Bury it? Burn it? Either way a waste of meat.

While I’d intended to ignore everything but the science, it’s proving incredibly hard! So my editorial for this story is that I’m not sure that killing the giraffe was the best idea. There were zoos that were offering to take the giraffe and, while it may not be the ideal option in terms of the breeding program, it is up to the zoo taking the giraffe to determine this. If they think the benefits of having another giraffe (and the public goodwill they will receive for offering sanctuary) outweigh the costs then I think this is their decision, not Copenhagen Zoo’s. The zoo needs to consider contraception as another instance like this will not go down well with the public and zoos are reliant on public support for their continued existence. I’ve seen several people say they will never visit the zoo and if they hold true to their word and their example is followed, Copenhagen Zoo is looking at tough times ahead.

Their decision to use the killing as an educational exercise was the best thing they could do, though I do find it strange that a lot of the outrage seems to be directed at the public nature of everything rather than the killing in the first place. The outrage is precisely why this should be done in public, though I do think the attitude of the zoo has been a bit too confrontational and almost designed to cause outrage.

Lions

Finally, the lions. Lions have been synonymous with Longleat for decades so to hear that they have killed six is almost unbelievable. As with all these stories there is public outrage, with people unable to understand how an organisation that has looked after lions for over 50 years can end up with killing an entire litter. As with all these stories, digging a little deeper reveals a more complex story. A statement from Longleat was given to HuffPo where they explained why they felt the litter needed to be destroyed. The cubs had genetic problems due to inbreeding which was could result in brain tumours and was already causing behavioural problems. From their statement,

“. . . all [cubs] individually exhibited adverse neurological signs such as ataxia, incoordination and odd aggressive behaviour that were not considered normal . . One of the cubs had to be put down because he was attacked by his brother and by Louisa [his mother]. The further lions referred to were put down due to associated and severe health risks.”

From this statement it seems that euthanasia was an inevitable and unfortunate consequence of inbreeding in their mother (breeding that did not occur at Longleat). It highlights why breeding programs must be carefully monitored and controlled and why animals like the giraffe should not enter the breeding population.

Conclusions

This has turned into more of an opinion piece than I’d intended which was, I suppose, inevitable considering the contentious nature of the stories. I hope I have shown that there are more to the stories than the headlines and they are more justifiable than they may first appear.

Zoos play an important role in conservation and education. They have to make difficult, unpopular decisions at times and when they do it is vital that they explain clearly their scientific rationale. The public are quick to react without getting all the facts and if you don’t explain your case carefully you risk a backlash that can have significant negative consequences. The science may be sound but the ‘politics’ surrounding the stories is more controversial and must treated with as much care as the scientific decisions that instigated them.

Author: Sarah Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image credits: Wikimedia commons