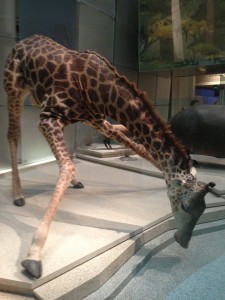

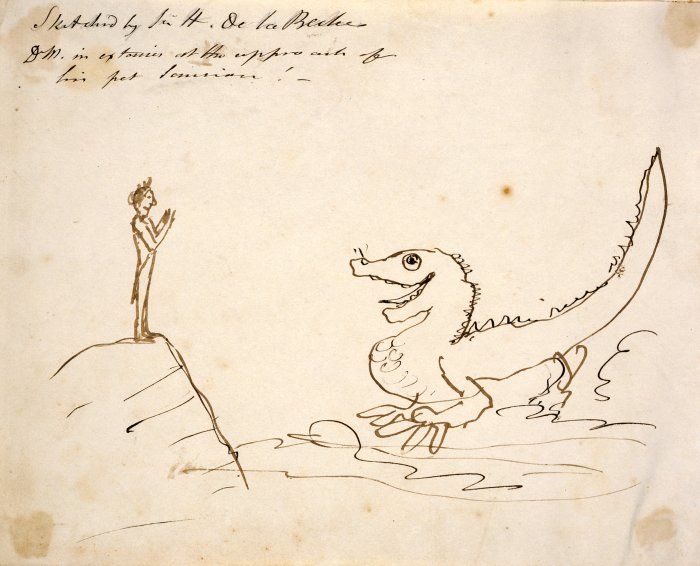

There’s an international celebrity star of the Victorian age directly above my office. He’s lived there long enough to see his museum home gradually shrink around him to such an extent that he no longer fits out the door. He will spend the rest of his days eavesdropping on undergraduate lectures, seminar presentations and NERD club meetings. Prince Tom adds a flavour of exoticism and royal blue blood to our Zoology Museum’s collections.

Tom was an Indian elephant caught from the wild and presented as a gift from the ruler of Nepal to Queen Victoria’s second son, the Duke of Edinburgh. Along with a tortoise companion, Tom accompanied the Duke on his visit to New Zealand in 1870. He lived and worked with the sailors aboard H.M.S. Galatea, partaking in the manual work of hoisting sails and enjoying his daily crew rations of rum – the quantities of which were up scaled so they were befitting an animal of his size.

As one of the first elephantine visitors to the land of kiwis, Tom sparked quite a publicity stir in New Zealand. Tom’s decidedly non-teetotaller ways were of particular interest; one journalist remarked that Tom “indulged in alcoholic stimulants, of which a temperance advocate might say, he was far too fond”. Tom was also noted for his gentle ways; bending down to offer rides to his adoring public and happy to accept treats of buns, biscuits and lollies.

Upon his return from the colonies, Tom was loaded onto a train at Plymouth bound for London. While he was, by now, accustomed to maritime transport, confinement in a train carriage was an entirely different matter. Amidst his attempt to escape, Tom crushed the Royal Marine corporal who had been entrusted as his carer. Clearly health and safety practices of the Victorian era did not stretch to include protocols for the safe transport of slightly tipsy elephants.

Tom was relocated to Dublin Zoo in June 1872 where he quickly became a star attraction. He gave rides to children and was, for a time, effectively given free-reign of the zoo (just a touch different to how the elephants are looked after today!) Tom’s most famous trick was to buy his own snacks from the food stands. He learned to collect coins in his trunk and hand them over in exchange for his favourite treats.

A few close encounters when Tom broke loose and “endangered himself and others” put an end to his free reign at the zoo and he spent his last few years confined to his house and small yard. He died in 1882 aged roughly 15; evidently his years of heavy drinking and fondness for pastries were not conducive to prolonging his longevity. His body was transported by barge from the Zoo to Trinity College where he was dissected “with the aid of shears, ropes and pulleys”, how I would have loved to attend that anatomy lecture!

Tom’s skeleton has remained in our Zoology Museum ever since. His celebrity status continues long after his death as he is now one of the main attractions of our new museum guided tours which start today. So if you’re around Dublin, come along and meet Tom for yourself, hear stories about our other famous animals and learn about our extraordinary collections which date back to the voyages of Captain Cook in the late 18th century. You never know what unusual tales lurk behind our taxidermied and skeletal remains.

Author

Sive Finlay: sfinlay[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Sive Finlay