Having just come through a particularly long and intense experiment (relatively unscathed) I thought I’d contribute some of the things I’ve learned and advice I’d give to other poor souls embarking on the exciting and terrifying world of empirical science.

Having just come through a particularly long and intense experiment (relatively unscathed) I thought I’d contribute some of the things I’ve learned and advice I’d give to other poor souls embarking on the exciting and terrifying world of empirical science.

1. Be organized!

I know this is a bit of a cliché but taking the time to work out exactly how much of everything you need, gather your chemicals, buying the labels etc.- it all pays off. Try, if you can, to run a number of pilots to iron out any blaring errors, work out difficult techniques and get familiar with how your system works. The absolute worst thing is to discover three days into an experiment that something isn’t working and you have to start all over again when you could have dealt with it weeks before.

2. Know your stats!

Another thing that I feel is really important and not always practiced or appreciated enough is to know what analysis you are intending to do with your results before you start. Understanding how you will analyse it makes a huge difference to the way and the efficiency with which you collect your data. Too many people don’t think about this in advance and the run into trouble once it comes to looking at their data. Knowing what you want from your data makes it a lot easier and straightforward to collect. It is also a lot more rewarding once you finish.

3. Accept you will have no life outside of work for the duration and share this fact

Realising this early is a big advantage. Warning friends and family in advance that you have time points that mean you can’t meet them in the pub, go for lunches or go away for the weekend saves frustration all round- they don’t think you are blowing them off and you don’t get that renewed sense of disappointment and questioning of “why am I doing this!?” every time you turn down an invitation for something more fun than looking down a microscope for 8 hours. It also saves boring them with your ‘hilarious’ “you’ll never guess what happened to me today? I held the pipette upside down!” stories that only you can appreciate right now, being the only thing to have happened to you all week.

4. Choose your listening and viewing carefully

Chances are you will be spending a lot of time alone and thus you will be turning to media for some company. I have a couple of pieces of advice about this. The first would be to not just rely on music. Singing along is fun for a while but the chances of a melancholic ballad coming on, or your dancing resulting in you knocking over bottles of liquid are quite high. Music all day every day for weeks also doesn’t do too much to pass the time. Chat shows or podcasts are great as you can let your brain engage they really make the time fly. I would also say to try and listen to a program that has the news on it so you remain somewhat in touch with the world. It is also a way of gaining perspective! A side note on TV as well, if you have late night time points, try to avoid too many murder mystery shows- leaves for an uncomfortable night alone in the dark lab in a creaking building!!

5. Make and effort to talk to people (and not just your equipment)

You can quickly cut yourself off from other people and goings on during your experiment and making an effort to go to coffee or pausing for a chat really can be the difference between going completely insane and being merely a little “frazzled”.

6. You’re probably a control freak- don’t panic if things don’t go exactly to plan

I imagine most people that have chosen to go down the empirical route have done so because underneath it all (or on surface!) you are somewhat of a control freak. You want to have power over your system, how it is designed and the kind of data you are going to generate. This is great but what it also means is that dealing with changes or mishaps can be hard. Most of the time these are things that can easily be adapted or fixed, so try not to cry when one thing goes slightly differently to how you had thought it would. Also, don’t count down the days. Take this from me, yes it is a comfort when you reach the last 2-3 days of the experiment but it isn’t much comfort waking up and saying “only 12 days left”. Definitely makes getting up harder!

7. Try to make it fun/pretty!

Experiments can be long, they can be tedious and they are exhausting. So why not do little things to make them just a little more fun and rewarding. Whether it is using one of your non-measuring moments to run and get your favourite coffee, buying sparkly labels and coloured beads to liven up your microcosms, or giving your equipment interesting names. These are all tiny changes that just might make coming into the lab that little bit brighter!

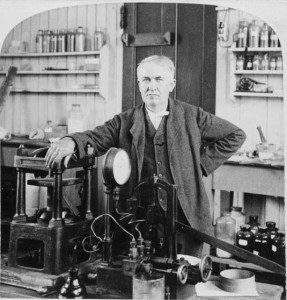

8. Embrace the insanity

If you are doing a long and time consuming experiment by yourself, you will go crazy. It is a simple truth. You reach a point where tedium meets stress meets exhaustion, and they seem to sum to delirium. However, embrace it, let yourself dance to that song when it comes on the radio while you’re pipetting, not chastise yourself too much for talking to the equipment (though see tip 4!) and remember that, in science, a little crazy is expected, even endearing. The mad scientist is already a thing, so you clearly aren’t going to ruin the rep.

9. Be prepared for the come down

This is kind of a strange one, but I think one of the more important ones. Your experiment will end (even if it doesn’t feel like it!). When it does, you need to remember that life is waiting for you again. I think it is a bit like finishing that first exam, it’s finally over and you’re delighted, but then there’s tomorrow to study for. Suddenly you need to make it up to friends, your emails, and your data. Try and prepare for this towards the end of your experiment: Glance at those unopened emails, file all those unread papers, sneak a brief peek at your diary beyond the page marked “end of experiment” circled a thousand times in red pen. This will make the day after the end of your experiment a little less of a shock!

10. Remember you are doing SCIENCE

The last thing and most important of all: Smile and remember, you’re doing that magical thing called science!! However tedious and time consuming, it’s amazing and exciting and you love it!!

Author

Deirdre McClean: mccleadm[at]

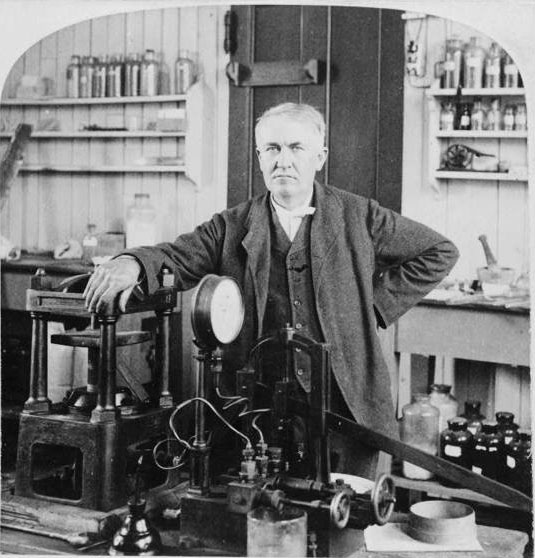

Photo credit

wikimedia commons