That was a recent hashtag in my Twitter timeline and it stirred me on to put this short piece together, so why would it cause me a thought? Well I’m a turfgrass professional, I have been maintaining amenity turfgrass and managing golf course surfaces for 30 years now and like most professions there’s more to it than meets the untrained eye. As I’m writing this the Premiership and Champions League have just re-started, the Curragh races are on down the road, Wimbledon and the RDS Horseshow are over, and the GAA football and hurling are reaching their climax, not to mention the cricket.……so? Well obviously, these all need quality turfgrass surfaces to allow the athletes perform to their peak ability and turf surfaces like these don’t grow on trees (oops).

Most people can cut grass ok, but getting the correct grasses to grow in the required manner 365 days of the year takes a blend of experience, craftsmanship and a good base of scientific research and knowledge. Experiences and craftsmanship can come with time, scientific knowledge can be obtained easily enough through many courses and colleges. My own personal career path began with learning the basic techniques and methods from other greenkeepers and participating in a number of certification courses, this allowed me to carry out the job of maintaining turfgrass surfaces adequately. However, I needed to know more and so I began a BSc in Turfgrass Science…..yes! there is a degree in that!

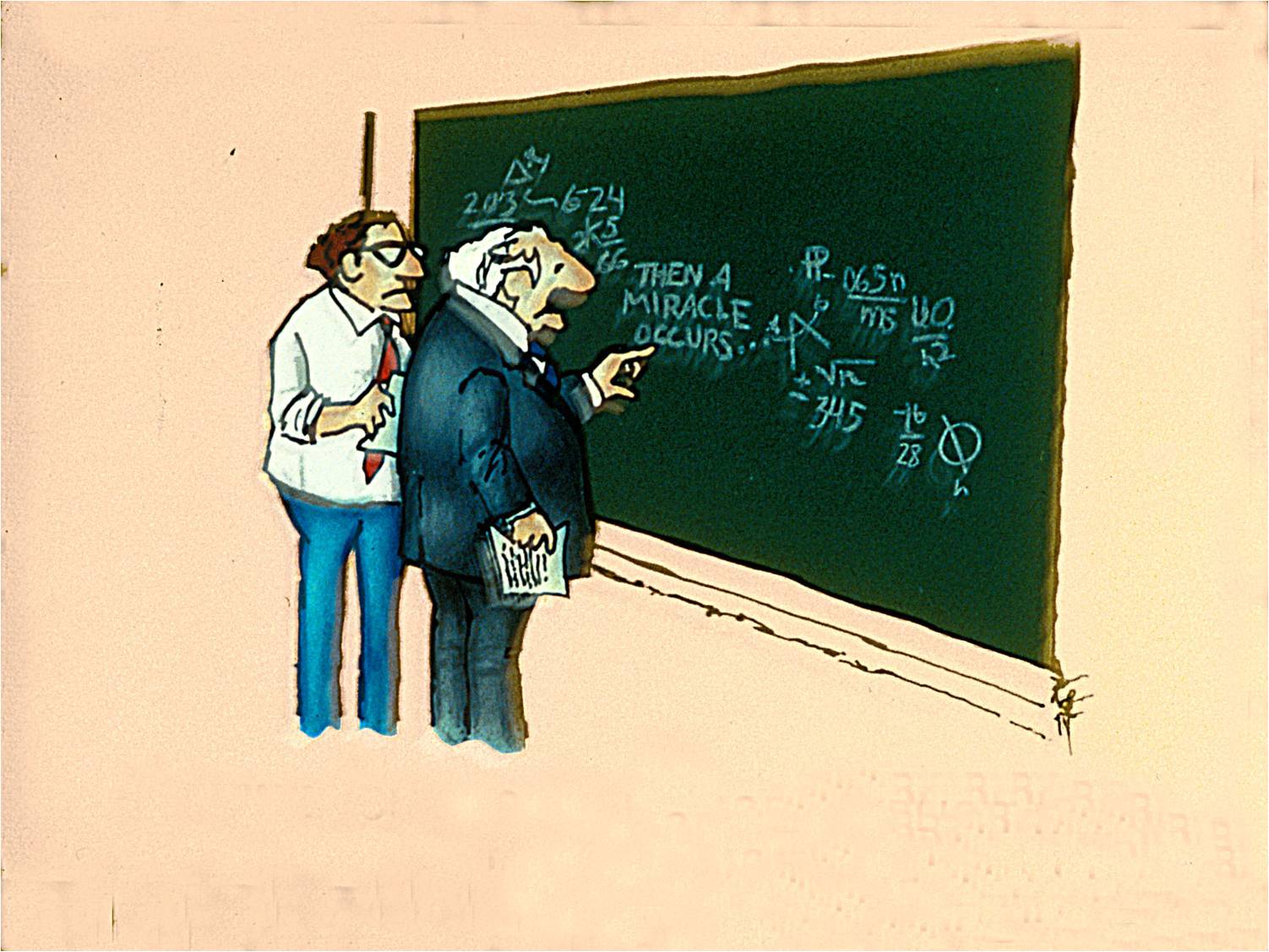

So we cut grass…is all this science necessary! Sure is; bear in mind the turfgrass manager is wholly responsibly for the maintenance and presentation of a multimillion Euro asset, be it a golf course in Ireland, soccer stadium in Spain, cricket grounds in England or the Olympic venues in Brazil! The BSc Honours degree requires passes in 20 modules, covering subjects such as plant biology and physiology, soil science, turfgrass species, cultivation and construction practices in sportsturf, drainage, irrigation, machinery management, research methodology and my favourite…pests and diseases! Upon completion of your degree, you have an understanding of the science required to produce quality sports surfaces used by many millions of people, either as participants or spectators. You can recognise the numerous genera and species of turf grasses and understand their requirements in terms of growth media, nutrients, drought tolerance and resistance or susceptibility to pests and diseases. You will have covered recent research into biochemistry and intracellular functioning of plants, advances in plant breeding, including plant tissue culture and molecular techniques…. relevant to all plants of course. You’ll recognise the numerous soil chemical and physical properties and their influence on plant growth and development, understand the dynamic process of plant growth, metabolism and reproduction and be able to specify the development and use of artificially constructed rootzones for the production of quality surfaces for a variety of sports.

So, do you know all about turfgrass science when you finish your degree?…………sadly no! If you’re smart you will probably understand how little you do know about plant science and how much more there is to be learnt. That was partly my experience: while I learnt a lot about the science behind the job I have been doing for the past 30 years, I realised there was a lot more I could do. In the final year, I undertook a research project on the suppression of fungal disease in trfgrass and it was an extremely interesting and successful project (I even got an invite to present it in France….nice!). This helped me decide to go the whole hog and started a PhD at the University of the West of England in Bristol and based in the Centre for Research in Biosciences. Currently I’m carrying out final amendments to my thesis for completion during 2016! The PhD is research based and involves alternative methods to suppress fungal infection in amenity turfgrasses. The research has produced interesting and novel data, which has significance to turfgrass disease control, but is also relevant to other grass species such as cereals, like wheat, barley and oats. Resulting from this I have been able to present the findings not only to turfgrass professionals in Florida (very nice!) but also to cereal scientists in Scotland and plant pathologists in England.

How does all this academic study complement my full time position as a turfgrass manager? Well firstly and obviously, it gives me a thorough understanding of the science involved in turfgrass, and plant science in general. I have developed transferable and personal skills in areas of communication, time management, work prioritisation, critical analysis and report writing. The progress through academia has given me the ability and confidence to interact with other scientists, agronomists, employers and my turfgrass peers. My PhD research has allowed me to develop methods and practices which have helped to reduce disease incidence on fine turf surfaces and enhanced their playing and visual qualities. This not only had a direct impact on my own place of employment, but is being adopted throughout the turfgrass industry worldwide.

Would I recommend this pathway of academic progress to others? Sure! Apart from all the positives mentioned above, working on a BSc or PhD is a great challenge, is very stimulating and can provide you with extreme satisfaction…..eventually!

Can anyone cut grass?…..sure, provided they can get it to grow in the first place!

Author: John Dempsey, University of the West of England, LinkedIn, twitter

Images: WikiCommons & Courtesy of John Dempsey.

Scientists as a demographic group tend to be atheists.

Scientists as a demographic group tend to be atheists.

“

“