The media love to brand cloning as an apocalyptic threat that involves mad scientists, evil doppelgängers, and mutated monsters like Frankenstein. Thanks to such misconceptions, cloning discussions highly focus on the idea of human clones and what this means for our individual identity. However, much like the Sun does not revolve around the Earth, life is more than mankind. This human self-entitlement draws away from the fact that cloning can be a tool used to right our wrongs, as cloning has the potential to save species that we have endangered or even resurrect species that we have driven to extinction. But before Jurassic Park and Ice Age fans get too excited, I’m here to convince you that we should focus our cloning resources on reverting species decline rather than de-extinction. Read on with an open mind and look past the assumptions that the media have distilled in how we think and understand the science of cloning.

Credit cover picture: USFWS Mountain Prairie is licensed under CC BY 2.0

To demonstrate how cloning can successfully save a dying species, I am going to take you on a journey as we explore the life, death and rebirth of a clone named Elizabeth Ann. Elizabeth Ann is a black-footed ferret whose species is native to the United States. In the 1970s, this species was thought to be extinct after farmers and ranchers destroyed the main food source of black-footed ferrets, the prairie dogs.

However, a ranch dog named Shep surprised the world when he uncovered a remaining population in 1981. These surviving black-footed ferrets were monitored intensely and the population seemed to be thriving, up until they were nearly wiped out by canine distemper and sylvatic plague. The very last 18 black-footed ferrets were rounded up and taken by the Fish and Wildlife Service before it was too late.

Of the remaining 18 black-footed ferrets, only 7 were successful in breeding and passing their genes onto offspring. As a result, all newborns arose from the same 7 founders, meaning all black-footed ferrets alive today are related. This incestuous existence creates a population with little genetic diversity which can wreak all sorts of havoc on the success and maintenance of a population. You see, differences and variations in genes are what enable a species to fight off diseases and better adapt to their surroundings. Without this diversity, a species is less likely to survive on this ever-changing Earth.

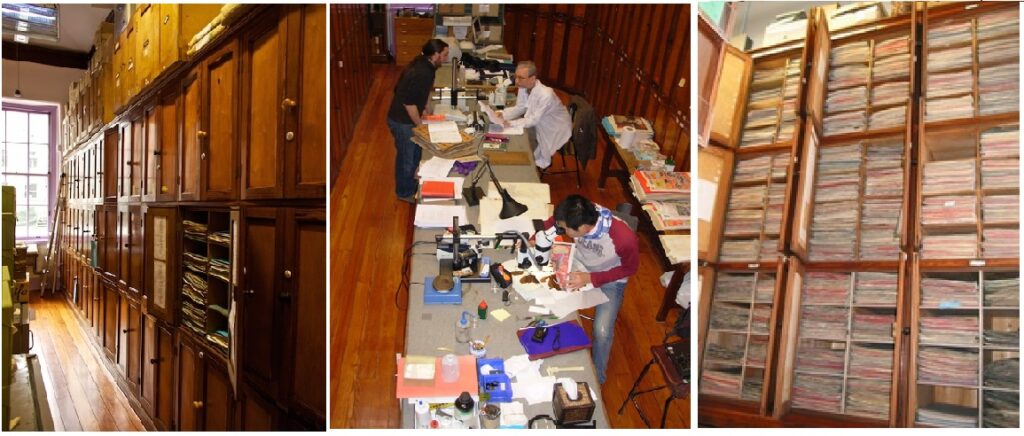

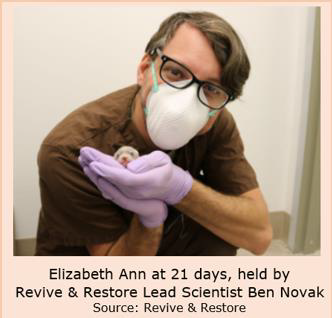

The black-footed ferret cloning process began when forward-thinking conservationists at the Wyoming Department of Game and Fish suggested that the cells of a female black-footed ferret, named Willa, be sent to the Frozen Zoo within the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) when she died in 1988, as Willa had a particularly diverse genome. These cells became one of the 1,100 cryopreserved (frozen) cells of rare, endangered, and even long-dead species who are silently waiting for technology to enable their return. 30 years later, Willa’s frozen cells were used to make Elizabeth Ann, along with the collaborative help from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, ViaGen Pets & Equine, Revive & Restore and the SDZWA.

The cloning process involved taking eggs from sedated domestic ferrets (a related species) and replacing the nucleus and genetic material of the eggs with the contents of Willa’s cells (picturing a yolk transplant between a chicken and a duck egg helps me make sense of it). The resulting embryos were implanted into a surrogate domestic ferret and, lo and behold one embryo took and a black-footed ferret foetus was conceived.

On the 10th of December 2020, Elizabeth Ann was born via C-section with tests on her 65th day revealing that she is, in fact, of the black-footed ferret species and a clone of the pre-existing Willa. The arrival of Elizabeth Ann brings new hope for the species as a broadening of the gene pool may help black-footed ferrets reproduce more easily and become more resilient to disease and environmental stressors. Therefore, cloning can aid in overcoming the genetic limitations that are disrupting the recovery of the endangered black-footed ferrets. If Elizabeth Ann successfully breeds and provides greater genetic diversity, this will legitimise cloning as a reproductive technology for the conservation management of black-footed ferrets and other endangered species.

Although cloning can be a successful way of saving living species from dying out, cloning specialists at Revive & Restore continue to work towards resurrecting extinct species such as the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth. But take note, bringing an extinct species back to life is very expensive, much more complicated, and highly controversial. There’s no knowing if an extinct species could even survive in the climate we have created today. So, let’s stick to what we know can work and clone to save our existing species first.

What do you think?

Keep up-to-date with Elizabeth Ann’s journey via the black-footed ferret conservation project Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/FerretCenter

References:

1. Maio, G. (2006). Cloning in the media and popular culture: An analysis of German documentaries reveals beliefs and prejudices that are common elsewhere. EMBO reports, 7: 241-245

2. Ryder, O.A. and Benirschke, K. (1997). The potential use of “cloning” in the conservation effort. Zoo Biology: Published in affiliation with the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, 16: 295-300.

Based on the ideas discussed in: Shapiro, B. (2017). Pathways to de-extinction: how close can we get to resurrection of an extinct species?. Functional Ecology, 31: 996-100.