As mentioned previously on the blog, Andrew Jackson and I started a new module this year called “Research Comprehension”. The module revolves around our Evolutionary Biology and Ecology seminar series and the continuous assessment for the module is in the form of blog posts discussing these seminars. We posted a selection of these earlier in the term, but now that the students have had their final degree marks we wanted to post the blogs with the best marks. This means there are more blog posts for some seminars than for others, though we’ve avoided reposting anything we’ve posted previously. We hope you enjoy reading them, and of course congratulations to all the students of the class of 2014! – Natalie

Here’s Sam Preston’s take on Dr. Nathalie Pettorelli’s seminar, “Monitoring biodiversity from space: a wealth of opportunities” and Gina McLoughlin’s views on Professor John Hutchinson‘s seminar, “Six-toed elephants and knobbly-kneed birds! Case studies in the evolution of limb sesamoid bones.”

———————————————————————–

Three New Reasons I Want a Satellite

Sam Preston

Despite the best efforts of Google spying on my house and Lee Tamahori making Die Another Day, I still think satellites are awesome. Who among us can honestly say that man-made objects floating in space aren’t straight up cool? And that’s without even considering what we use them for. Where would we be without the internet, or GPS? Probably outdoors, and lost.

But satellites have utility that extends beyond the realm of kittens in top hats, as Dr. Nathalie Pettorelli from the London Zoological Society knows. She gave a memorable seminar on the use of satellites in biological research, single handedly doubling the number of items on my “Reasons I Want a Satellite” list.

1. Vegetation Surveys

The point of owning a satellite – apart from the prestige and party scene – is being able to do cool stuff with it. Unfortunately, most satellites don’t have the kind of firepower necessary to ransom the Earth, but they do have cameras, and there are a lot of uses for a camera in space. For the botanically-minded, vegetation surveys are one possibility.

Working out what trees and how many are in a particular place can be time consuming. You have to go out, pick survey plots, count and identify trees, often in very remote locations miles from the nearest western toilet. Not when you survey via satellite.

To conduct a satellite survey you simply wait until your satellite is overhead, then take pictures. The scale of these pictures can vary from a few tens of centimetres to metres, and once you have them you’ve saved yourself a lot of time, money, and effort. Then you can use your satellite images to spot illegal logging of rainforest, or examine how storms affect mangroves. Best of all, your camera isn’t restricted to what your eye sees. By examining the relative amounts of red and near infrared light reflected from the Earth’s surface, you can determine the “greenness” of vegetation, assess its seasonality, and judge its composition, all of which is vital for finding habitat for reintroduction programs.

2. Multi-Scale Ecology

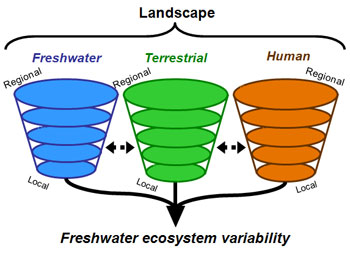

Two of the seminars we’ve enjoyed have been about ecological scales. Unfortunately, it’s often difficult to obtain data on the largest scales, so unless you’re willing to put in obscene amounts of work and time, you’re not going to get any meaningful information. That is, unless you have a satellite.

Once again satellites trump doing things by hand. They can survey large areas much more quickly and many times more than even the most dedicated research team, and depending on what you’re looking for can provide highly valuable information. Want to assess eutrophication of freshwater? Check out the “greenness” of the lake’s phytoplankton. Want to determine the clarity of the water? Use lasers emission and work out the absorbance rate. If the phenomenon you want to study affects light absorption or reflection in any way, then satellites should be up to the task.

3. Counting Penguins

By now you’ve noticed the theme of my satellite-based projects. When it involves very large – or just difficult to reach – areas, then you can probably do it faster by satellite. But satellite projects aren’t just limited to plants and ecosystems. They can be just as useful for surveying animals over large, hard to reach areas, and there are few areas as large or hard to reach as Antarctica.

If you’ve ever wondered how many penguins are at the south pole, you’re not the only one. We’ve all pondered the number of well dressed birds that manage to carve out a stylish existence on the ice. One research team, however, decided to do something about it, and – you guessed it – they did it with satellites.

The idea is brilliant in its simplicity: take photos of penguin guano from space. Yes, that’s right: millions of euros of equipment used to photograph poo. From space. That has just the bizarre and disgusting ring to it that marks a good zoological study. Outlandish as it may sound, using this method the team discovered 10 new penguin colonies in Antarctica! What’s more, using satellites operating at a finer scale, other researchers were even able to estimate the sizes of penguin colonies!

To sum up, satellites and biological research go hand in hand. No longer is space the privileged realm of the physicist looking down on the (erroneously) perceived softer scientists. Zoologists, botanists, and ecologists have carved out a territory in orbit. There are a lot of questions we’ve yet to face, but the answers are out there.

—————————————————————————–

Walking on Tenderfoot

Gina McLoughlin

Being an avid follower of a blog called What’s in John’s Freezer naturally I was extremely excited when Professor John Hutchinson from the Royal Veterinary College, London came to give us a seminar. He gave a very interesting and entertaining talk on 6-toed elephants and knobbly-kneed birds: Case studies in the evolution of limb sesamoid bones. Hutchinson explained to us about his recent research into the tiny sesamoid bones, such as the patella, that are found in the limbs of many animals. Sesamoid bones are small “bits” of bone that are generally located in a tendon or near a joint (Sarin et. al., 1999). Their function is not fully understood but it is hypothesized that they may play a role in changing the direction of muscle forces in a limb or may play a role in protecting the tendons.

A very interesting case of such sesamoid bones, which Hutchinson talked about, is found in elephant feet. Elephants, like humans have 5 toes but unlike humans they stand on their tiptoes and have a hoof-like sole. They have a fat pad at the heel of their foot, which acts as a cushion and supports the toes. It is here, buried deep in the fat tissue that the pre-digit bones are found. Hutchinson explained they are like a 6th toe that can be found in both the front and the back feet. The bones are known as the prepollux and prehallux and they connect to the real toes just under where our thumb is (Hutchinson et. al., 2011). They are cartilaginous for most of the elephant’s life, but do eventually ossify when the elephant gets older. Again, the function of these sesamoid bones in the elephant is not fully understood although Hutchinson proposed they could be used as levers for extra support due to the weight of the elephants. Another hypothesis is that instead of developing a single hoof, like in a horse, the elephants use this pre-digit to distribute their weight more evenly on each foot (Hutchinson et. al., 2011). However, these pre-digits have been observed in other animals and have different functions than what they have in the elephant. Most surprisingly to me was that they are found in pandas. Here, they are used for grasping bamboos while eating, kind of like a false thumb. Their 5 fingers close over the false thumb, which has evolved by enlarging the radial sesamoid and functions as an opposable thumb (Endo et. al., 1999).

A thought provoking point that Hutchinson made in his seminar was how do such small bones cause big problems in animals. These bones can cause such big problems that it almost makes big animals appear very fragile. For example, elephants in zoo need to have their feet very well looked after to prevent them from going lame. Hutchinson explained that if an elephant goes lame due to a sesamoid bone problem it is more than likely that the elephant will be dead in approximately 5 years time, as it is very hard to fix and they are in a lot of pain. Likewise, giraffes need a lot of hoof-care to prevent their sesamoid bones from dissolving completely. This would cause the giraffe to go lame and prevent them from thriving.

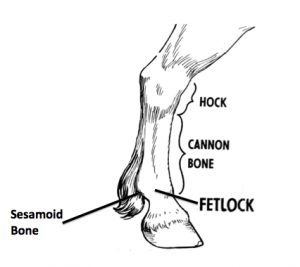

A more common animal example of a sesamoid injury that I find very interesting, and an area where more research needs to be carried out, is in horses. The sesamoid bones from which most injuries occur are located in the lower limb, at the back of the fetlock joints in the both the fore and hind limbs (Figure 1). In horses it is hypothesized that these bones are used as a pulley for the suspensory ligament as it passes over the back of the fetlock joint. They are very important in the mechanical functioning of the fetlock joint. Horses in competitive sports, such as show jumping and racing frequently suffer from sesamoiditis (Spike-Pierce & Bramlage, 2003). This is commonly caused by heavy loading on the limbs and over-flexion of the fetlock joint, which can result in the sesamoid ligament tearing. This extra pressure can lead to increased internal bone stress, which may lead to a fracture of the sesamoid bones. Faulty blood flow to the bone can be a result of this damage and demineralization of the bone can occur.

Thankfully, most cases of sesamoiditis can be treated with anti-inflammatory medicine, cold therapy and support strapping or bandaging. However, in more serious cases where a fracture has occurred the horse may never return to the top of their sport due to the damage (Kamm et. al., 2011). Once a sesamoid bone is damaged they are very difficult to cure because every time the animal walks they put more pressure on the bone, preventing it from healing.

By the end of the seminar I was amazed that such small bones could be so interesting. I would never have though that these tiny bones could be the cause of such big problems not only in competitive horses, but also in large animals such as elephants. Overall, I really enjoyed Hutchinson’s talk. I thought he was a very good speaker and I would now possibly consider doing some research in this area myself.