Whenever I go home I repeatedly deal with the age old question non-academics ask academics: what do you actually do? I always find this a tricky question no matter who asks. Some people have tried to make it easier by asking me to describe a typical day or week, but this doesn’t really help as it changes a lot from week to week! In 2014 I attended five conferences and two workshops, did two weeks of fieldwork in (cold and wet!) Madagascar, and gave four seminars at different universities. I also worked on at least ten completely different research projects with different groups of people. Most weeks I’d work on one of those at least a little. But other than the research, I don’t really have an “average” week. Most weeks I’ll attend NERD club, and a meeting (or five) and I usually interact with my PhD students to some degree. But the exact details depend on the time of year (exam season/term term/outside term time), and where I am with projects, grant deadlines etc. So instead of specifically telling you what *I* do, I’ve compiled a list of the kinds of activities professors/lecturers are involved in.

Professor/lecturer jobs are often split into three areas: research, teaching and admin. However, I prefer to think of it in the same terms as on our promotion forms: research, teaching, service to your institution and service to the community. Admin sadly forms part of all of these things, like a layer of really horrible jam sticking together the cake of academia. All of these things also seem to involve a lot of emailing. If you defined my job by what I spend most time on, I’m probably a professional emailer…

Research includes fieldwork, lab work, analyses, coding/programming, planning future projects, managing finances, supervising PhD students and postdocs, writing press releases, reading papers/books, writing papers/books, writing blog posts about research, grant writing (this is the worst!), attending conferences, networking, writing reports, attending journal clubs etc.

Teaching includes giving lectures and tutorials, supervising labs, preparing lectures and labs, getting materials for labs, setting and grading essays, supervising projects and desk studies, giving careers advice, writing reference letters, putting teaching materials online, arranging timetables and room bookings (and dealing with the inevitable mix-ups that occur), providing extra reading, marking exams, invigilating, checking attendance, advising students who are experiencing difficulties, being a personal tutor etc.

Service to your institution includes sitting on committees, acting as Director or Dean of some administrative entity, promoting the institution via social media and/or traditional media, helping at Open Days, organising seminar series, providing graduate student training, internal examining theses, interacting with alumni, organising journal club, being a representative at meetings (e.g. Athena SWAN, departmental, Faculty etc… ad infinitum).

Service to the broader scientific community includes teaching on workshops, creating online tutorials, reviewing papers, being a journal editor, sitting on society committees, organising conferences/symposia/workshops, giving seminars at other institutions, organising outreach events, writing advice based blog posts, grant reviewing, organising cross-institution journal clubs etc.

There are probably many more, but this is what we came up with in half an hour!

As you can see it’s a pretty diverse job! Strangely we are mostly trained as PhD students and postdocs to do research, some service to the broader community and a little bit of teaching. This is worth bearing in mind when deciding whether a career as a professor/lecturer is right for you, as research is definitely only part of the job (at some times of year it’s very difficult to do any research at all!). However, many of the additional duties are really interesting and fun, and things like teaching and supervising students are really rewarding.

These are quite general things we do as professors/lecturers. But hopefully this is helpful if you’ve ever wondered why we’re always moaning about being busy! One final point – in general, professors/lecturers *do not* get the summer off work. My ex’s mother was convinced that I had the best job in the world because I only had to work from late Sept to June. If only that were true!

Author

Natalie Cooper

nhcooper123

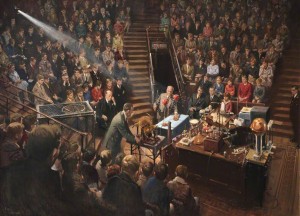

Photo credit

Cuneo estate / Bridgeman Images

The Royal Institution

Dear Dr. Jeal,

Dear Dr. Jeal,