What do you associate with the word “extinction”?

What do you associate with the word “extinction”?

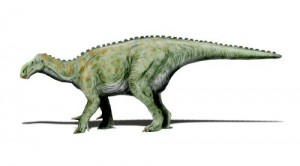

I think of death, dinosaurs, dodos, desolation and despair (well maybe the last ones are a bit overly dramatic but I was feeling the alliterative vibe). No matter what your initial reactions may be, I think the concepts of extinction being irreversible and ultimately a “bad thing” would feature in most of our reactions to the word. It turns out that neither of these initial associations is necessarily true.

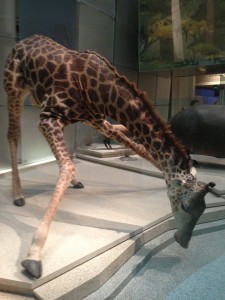

Extinctions are not always bad. It is all too easy to overlook their important role in shaping the evolution of life, a topic explored in a fascinating exhibition now on at London’s Natural History Museum. Extinction is arguably just as important as speciation in the evolution of our ecosystems so to think of it in a completely negative light is misguided.

However, extinction’s negative connotations are still very much justified. When humans mess with “natural” extinction trends is where we encounter problems. It’s a sad but true cliché that where humans go extinctions swiftly follow. Humans were either the direct cause or a major contributing factor in a depressingly long list of extinctions; from dodos and Tasmanian tigers to passenger pigeons and giant moas. When the last individuals of these species were either killed or lived out their days in captive isolation they marked one more reduction to global biodiversity and another page in the annals of the history of human stupidity and greed. Yet their extinction pronouncements may not be as final as they seem…

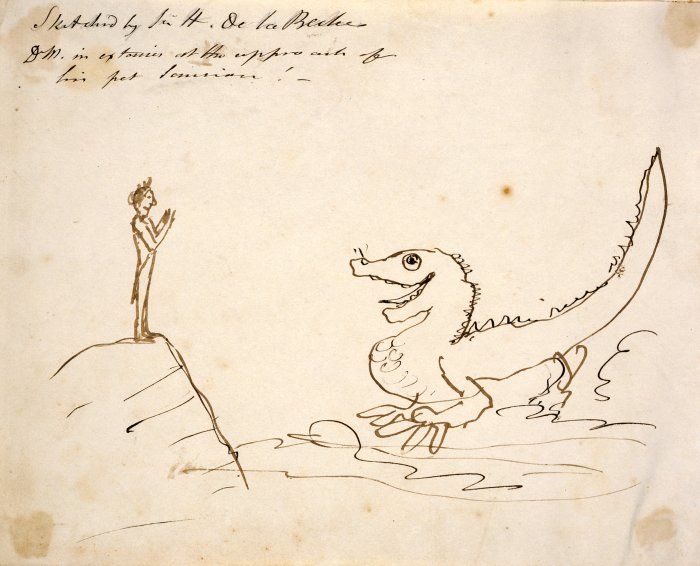

On the back of a recent TED special event, de-extinction is receiving increasing levels of attention and interest. The key concept arises from the intriguing difference between individual and genetic extinction; if DNA is salvageable then the possibility of raising species from the dead remains open. It’s a very attractive idea; extract some DNA, conduct some genetic jiggery pokery (can’t you just see my genetic expertise) to create viable stem cells or embryos, find a living relative of your target species and hey presto; an elephant gives birth to a woolly mammoth. The difficulties are found within the jiggery pokery steps; how to get enough good quality DNA to create viable stem cells and whether you can make a “pure” embryo of your species or create some kind of hybrid between living and extinct species. Despite the difficulties, the project to revive passenger pigeons is already underway with other candidate species including woolly mammoths, sabre-toothed cats and the great auk waiting in the wings.

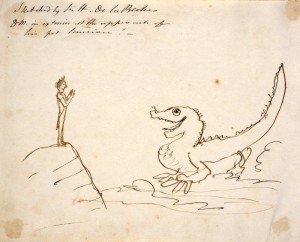

The idea of coming face to face with a giant elephant bird or having your very own pet dodo is exciting to say the least – think of the revenue of a zoo which offered rides on a woolly mammoth! Yet de-extinction is a veritable minefield of ethical, ecological and legal debate. One of the main concerns, which I share, is the worry that even remote chances of successful de-extinction could detract from conservation efforts to save very much alive but critically endangered species. If we lose living species we can’t just 3D-print carbon copies and plonk them back into their habitats. De-extinction should be seen as a difficult, expensive and ultimately very risky last-resort measure to regain lost biodiversity, not an alternative to protecting what we have now.

Conservation issues aside, if by any chance we did manage to successfully re-create an extinct animal what happens next? Would it just become an expensive sideshow attraction at some zoo or, perhaps, have a glittering movie-star career (creating employment for the sabre-toothed cat animal trainers of tomorrow)? There are arguments that, with mass-scale de-extinction and subsequent successful breeding, new populations of revived species could be re-wilded back into their natural environments and help to restore ecological functioning. It sounds great but, given our chequered history of ecosystem meddling through species introductions it’s difficult to see how we could accurately predict or control what would happen if we introduced genetically engineered species into habitats which, most likely, have undergone extensive ecological change in that species’ absence.

De-extinction research is undoubtedly fascinating from a purely technological and scientific point of view. Furthermore, the prospect of reclaiming species from the past is sure to excite the latent Jurassic Park Ranger career aspirations of all of us. However, the controversies surrounding the process are well-justified and it’s clear that we have a long way to go before booking our next woolly mammoth safari holiday.

Still, perhaps the phrase “dead as a dodo” does not have as final connotations as we once thought…

Author

Sive Finlay: sfinlay[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Wikimedia commons