I was recently asked to write a blog post for SpotOn (Science policy outreach and tools Online) and thought I’d share a modified version of it here. If you’ve never heard of it, SpotOn is a series of community events hosted by Nature Publishing Group for the discussion of how science is carried out and communicated online. There are loads of excellent resources on the website which I’d urge you to check out if you’re at all interested in using the internet more in academia. I will probably write more blog posts about this in the next few weeks. Anway, here’s my post:

SpotOn London 2012: How to save time with twitter

Productivity gurus suggest that when faced with a list of tasks you should divide them into urgent and non-urgent, and important and unimportant tasks. Important urgent tasks should be prioritised; non-urgent unimportant tasks should sink to the bottom of the pile. Defining what is urgent is one thing, but defining what is important is quite another! Certain things are clearly important. But what about online activity such as writing blog posts or using twitter? Is that important?

Until recently I would have said no, but in August I decided to sign up to twitter (prompted by an excellent article in the BES magazine by @Philip_A_Martin). At first I felt I was getting very little out of the experience, except finding yet another way to waste my increasingly precious time. But then I realized the time I was spending on twitter was one of the highlights of my day. I was finding out about new research, gaining teaching materials, discussing science and networking with people across the globe. All in my pyjamas while drinking my morning cup of tea! This has led me to believe that almost every part of life as an academic can be enhanced by using twitter and, perhaps more importantly, that using twitter can save time in the long run. This may seem like a rather grandiose claim but I’ll try and convince you!

Networking and promoting your science

Perhaps the most obvious use of twitter is to promote your science and to network with distant colleagues -@mickresearch really impressed upon me the benefits of being able to have a global network of colleagues without having to spend time (or increase your carbon footprint) travelling. I’ve also seen examples of research collaborations started by discussions on twitter and, as many people have pointed out, it’s easier to network at conferences if you’ve already interacted with someone online. Thus twitter allows you to use your limited time at conferences much more efficiently. Twitter is also an effective way of promoting your papers without the need to write a long press release – 140 characters and a link to the webpage and you’re done!

Teaching

I rarely have time to trawl the literature for new and exciting examples to engage my students and keep my lectures up to date, but with twitter I don’t have to. My twitter feed is full of interesting new papers, blog posts, photos of crazy creatures and titbits of information that help me liven up my lectures. And I’m only minimally using twitter’s capacity to enhance teaching. Teaching through twitter is also an option: recently @Drew_Lab gave a lecture to students via twitter because they couldn’t make it to class after hurricane Sandy. The students were able to ask questions and have discussions, and people outside the class also joined in (although @Drew_Lab did briefly end up in twitter jail in the process!). This could be a wonderful way of supporting flexible working practices.

PhD student supervision

In our school, students are expected to complete their PhDs in 3 years, so efficient supervision is critical. However, I don’t have the time to teach them everything they need to know in a timely fashion. Currently my focus is on helping them to plan their projects but they also need training in data management before they start generating data. Luckily twitter saved the day again with some excellent slides and a help document on data management from @carlystrasser. This saved me time now, and possibly countless hours in the future as I won’t need to help them sort out badly organized data when they get to their analyses.

Research

Another thing I rarely have time for these days is reading research papers. There are so many that it’s hard to even find time to read all the abstracts, let alone get any idea of the methods employed. Again twitter helps. People post information on new papers they’ve read and found interesting; they post links to blogs about papers that are much quicker and easier to read than the full paper. There are also lots of posts about new methods, R packages, statistical issues and new datasets. Knowing the up-to-date consensus on analytical methods can save lots of time dealing with referee’s comments in the future! Using twitter gives me a little time each day to think about these kinds of things, and to consider new avenues of research. Without this opportunity I could go for weeks thinking about nothing other than my next lecture!

Science policy

@AtheneDonald recently pointed out the large number of science policy makers found on twitter. Science policy, whether it be promoting women in science, the proposed badger cull, or changes in the kinds of research funding bodies will support, is really important to all of us. But finding time to process all of this information is impossible. Twitter gives me a quick digest of the major issues, and alerts me to things that I will need to act on in the future.

Sense of community

Finally, I think this is the nicest, and perhaps most often overlooked, aspect of twitter: the sense of community. It’s far too easy to feel overwhelmed by the extreme pressure of academia, no matter what level you’re at, and to feel as if you’re the only one who isn’t coping. This may go some way to explaining the “leaky pipeline” for female scientists. So it’s reassuring to see other academics tweeting about the stress they are under balancing work and home life, or their difficulties in writing grants, getting papers published or finding a job. It’s also wonderful to see people supporting one another through these crises. I think this aspect is particularly important for women, parents with young children and people with flexible working hours, who may lack the support network they need in their own institutions.

In conclusion, I think the benefits of twitter go far beyond those of promoting yourself online. Although it takes time, if you can manage that time into sensible short blocks I think you can save yourself time in the long run. And if you’re a busy junior faculty member like me (or a busy senior faculty member for that matter), being able to discuss research on twitter can remind you why you got into academia in the first place!

Author

Natalie Cooper: ncooper@tcd.ie

@nhcooper123

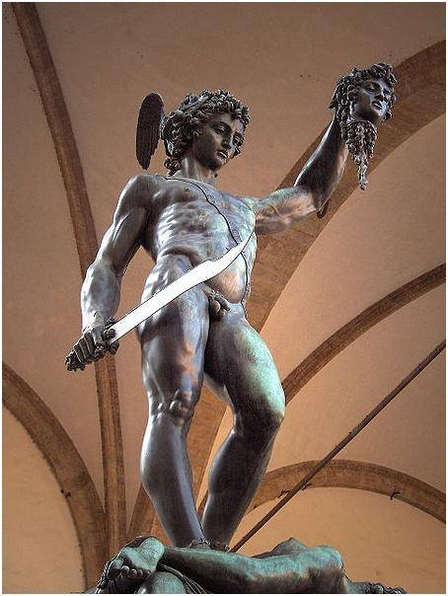

Photo credit

wikimedia commons