In my last post I wrote about the case for scientific whaling. I tried to be objective and leave moral and ethical considerations out of the discussion to focus solely on the science. Yet it is impossible to avoid these considerations for long. The use of animals in scientific research has a long history and has engendered debate for much of that time. Legislation to protect animals against being used in painful experiments was introduced back in the 19th Century through the Cruelty to Animals Act which became law in 1876. Amendments have been made to provide greater detail on what and is not permissible, in Ireland most recently in 2002 and in the UK in 2013.

The ethics and utility of animal research is a massive and complex topic and one which I cannot hope to cover in a simple blogpost. It is also a highly contentious topic with advocates on both sides of the debate. Most of the controversy surrounds the use of animals for medical research and cosmetics testing which has been argued against by organisations such as the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV) and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Looking at their websites you would quickly believe that all animal research was pointless and cruel. One statistic on the BUAV website is that only 13% of animals used in the UK are for medical research. This is true, but it’s only part of the story. UK government statistics from 2011, the most recent year with available figures, show that almost 3.8 million vertebrates were used in animal research, of which almost 43% were used in the breeding of genetically modified or harmful mutant animals and 35% were used in fundamental biological research. So while the impression being given by the BUAV is that 87% of animal experiments are a complete waste of time, the reality is a bit more complicated than that.

However, I don’t wish to use my time here to debate the use of animals in medical and cosmetics testing. I don’t have the expertise to discuss the rights and wrongs of medical testing and cosmetics testing is a largely moot point as it is banned in the EU. What I would like to discuss is the use of animals a wider context and examine why we care more about some animals than others.

The Cruelty to Animals Act specifically and exclusively protects vertebrates. The UK amended their version of the law in 2013 to extend this protection to cephalopods. Yet this Act and its companion, the Animal Welfare Act 2006 only cover vertebrates and also exclude certain activities, most notably fishing. (Apologies for referring to the UK versions of these laws, I was unable to find the Irish equivalents. The closest I could come to the Animal Welfare Act was the Animal Health and Welfare Bill which is still in draft form).

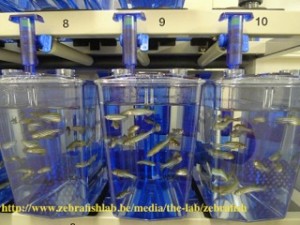

It is here that I want to start my discussion. Why are fish that are kept as pets or used in laboratories covered by law against being treated cruelly yet fish that are caught by a recreational angler or a commercial fisher not? According to the figures, 563,903 fish were used in scientific research in the UK in 2011. In the same year the UK caught 12,700t of cod or approximately 1.6 million fish. Just one fishery accounts for almost 3 times as many fish as were used in all of scientific research yet the law does not concern itself with their wellbeing. Why not?

The obvious reason is cost. Can you imagine the time and effort required to humanely euthanise every fish as it came on board? It would be completely unmanageable and would make fisheries impossible to be commercially viable. But it does raise the question of why we care about the fish in labs but not those on boats. They’re still vertebrates, a group we have deemed worthy of protection, yet when it comes to the choice between humane handling or cheap fish and chips we chose the latter with little difficulty. I’m not saying this is right or wrong, just that it is interesting.

Going back to my previous post, it would be hard to find someone who was indifferent to the suffering of the whales killed for their stomach contents. Yet my alternative option of killing thousands of krill would likely raise little or no reaction. Why are a thousand deaths preferable to one? This is even more puzzling when you consider that until recently whales were seen as little more than as a source of food, oil and baleen. They have gone from being the marine equivalent of cows to a creature people pay huge amounts of money to see.

These may seem like facetious questions unworthy of dignifying with a response. We protect whales because they are intelligent animals who clearly experience suffering. Krill, on the other hand, are effectively prawn crackers without the cracker and are undeserving of concern. But again I’d ask, why? Why is intelligence the marker we use for whether something is worthy of compassion? Why would we happily kill thousands of invertebrates to save the life of one vertebrate? And why are some vertebrates more worthy than others? Efforts have been made in recent years to make whaling more humane as we have come to appreciate whales for more than their commercial value yet there has been no attempt in other fisheries. Fish and squid still suffer agonisingly slow deaths on board fishing vessels around the world while their lab-based compatriots are given lives of luxury followed by an endless sleep induced through overdoses of anaesthesia.

It is human nature to value some things over others. We care more about our family than we do strangers on the other side of the planet. I suspect that this in-group favouritism extends to the animal kingdom which is why we care more about primates than mice, and more about mice than fish, and more about fish than snails. I also suspect there is an element of “appeals to cuteness”. Seeing a dog staring at you with big puppy-dog eyes pulls at the heartstrings in a way a snail can never achieve. Yet while it is understandable, I guess my final question is, is this justified? Should we really care more about cute mammals than ‘slimy fish’? Should our level of caring be contingent on the economic consequences of caring? All other things being equal, if research is worth doing does it matter if it’s done on a snail or on a mouse, and if it doesn’t should the snail be the animal used every time?

I don’t have answers to any of these questions. There may not be answers to these questions, or at least not objective answers. However, just because they may not be answerable does not mean the questions should not be asked. Animal research is a vital part of biology. Even if medical testing stopped tomorrow, animals would still be used in research laboratories for a host of legitimate and necessary reasons. It will likely always be a controversial subject and we owe it to ourselves and the animals to continue to question our assumptions, biases and justifications for our utilisation of animals in scientific research.

Author: Sara Hearne, hearnes[at]tcd.ie, @SarahVHearne

Image source: Wikicommons