On the 31st January, stimulated by a European Food Safety Authority report, the EU proposed banning three neonicotinoid insecticides which have been implicated in causing honeybee decline. These insecticides are widely-used, systemic (i.e. soluble enough in water to move around the plant’s vascular system to nearly all plant tissues), and, like nicotine, affect the insects’ central nervous system. They are highly effective at reducing insect pests that feed on crops and reduce yields and value, and many farmers are concerned about the effect the proposed ban will have on crop production. But these insecticides can also end up in the nectar and pollen of crops (as well as in the soil and in non-crop plants), and thus can have unintended side-effects on beneficial, nectar-feeding insects, who act as pollinators. Especially bees.

Bee decline has become a hot topic with scientists, the media, the public and even some politicians, but until recently the threat of neonicotinoids to bees has not been seriously implicated in their decline. Concern about pollinator decline is a result of the important role that pollinators play in food production: 75% of crop species depend on animal pollinators, which translates into 35% of global production; and the total annual economic value of pollination has been estimated at €153 billion globally. In addition, pollinators are fundamental to most terrestrial ecosystems, and indirectly affect the availability of food for other organisms (e.g. fruits and berries for frugivorous birds), as well as the structure and functioning of ecosystems.

So here’s the paradox: flower-visiting insects including bees are really important for agricultural production. But so is the use of neonicotinoid pesticides. Which is more important and is the ban justified on scientific grounds?

In the last year, the evidence that neonicotinoids have negative impacts on bees has been mounting. Bees and other flower-visiting insects are exposed to neonicotinoid pesticides in multiple ways: during planting of seeds which have been coated with pesticides as a pre-planting treatment, by collecting pollen and nectar from the crop, and by foraging on non-crop plants which take the pesticide up through the soil. Traditionally, toxicological tests of agrochemicals are carried out on the managed honeybee Apis mellifera, and pesticides are rated according to their lethal effects (by calculating the LD50 – the dose required to kill half the organisms tested after a specified duration). But the biology of Apis and all the other bee species (20,000 of them worldwide) is different. Can we generalise about effects on Apis, to effects on other bee species, and other pollinating insects including hoverflies and butterflies? And what about sub-lethal effects, i.e. those that don’t kill the insects, but affect their physiolology, behaviour and fitness?

Neonicotinoids are highly toxic to insects – that’s the whole point of them. Bees are insects. So it shouldn’t be too much of a shock that they kill bees. Last year it was shown that neonicotinoids can also have sub-lethal effects in honeybees, by decreasing foraging success and navigation by individuals back to the hive. At the same time, the neonicotinoid pesticide, imidacloprid, can reduce bumblebee colony growth and fitness by affecting their feeding behaviour. Some dissenters have cast doubt on the field-relevance of laboratory tests, claiming that field-realistic dosages have not been used, but this is not the case – the concentration of imidacloprid in oilseed rape flowers for example has been found to be 4.4-7.6 mg/kg in pollen and 0.6-0.8 mg/kg in nectar, which was within the range tested on bumblebees. This is pretty convincing evidence that neonicotinoids can cause very adverse effects on populations of these social bees.

Although neonicotinoids are not the only cause of widespread bee decline, they are more than likely contributing to it. Some of the agrochemical companies are claiming that bee decline has nothing to do with their chemicals and instead blame decline on Varroa destructor, the parasitic mite which infects honeybee colonies. Whilst Varroa probably plays its part in honeybee decline, the most probable cause of decline in other bee species is multiple pressures, including habitat loss and loss of forage plants, AND the use of neonicotinoid pesticides.

So should these insecticides be banned? YES, if we want to address pollinator decline. They should not be used for insect-pollinated crops, and wind-pollinated crops that insects forage on (including maize). But what’s the alternative for the farmer? How can crop production be maintained in the absence of these chemicals? Use something worse? If we’ve learned anything since Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” published 50 years ago last year, it’s that an alternative will be found, and we can’t be sure that this won’t be worse for the bees and other pollinating insects.

Author

Jane Stout: stoutj@tcd.ie

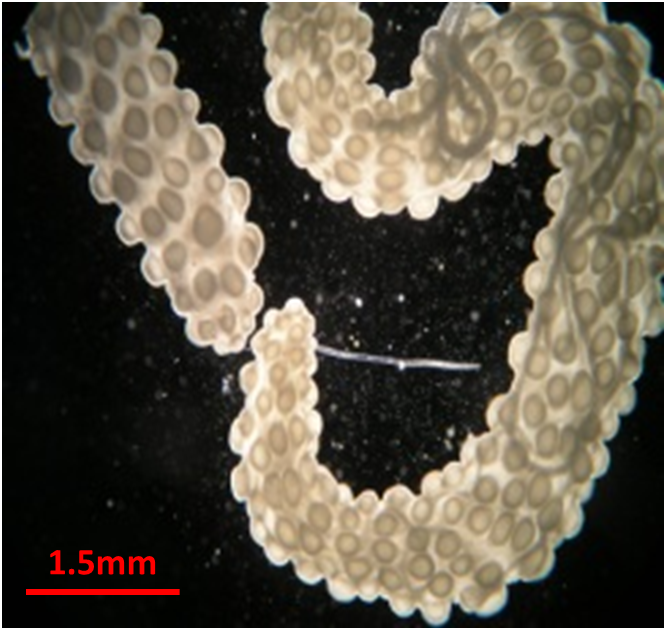

Photo credit

wikimedia commons