Conference attendance can really impact your development as a Ph.D. student and give you great ideas for future collaboration and research. In March, I was lucky enough to attend the 2015 Benthic Ecology Meeting (or Benthics) in Quebec City, Canada. The Benthics meeting focuses on the ecology of the bottom layer of water systems, and this conference is mainly marine in focus. There were lots of great talks, one epic toboggan race, and nearly unlimited opportunities for networking and discussion. A quick overview of my three favourite talks is below. Check out what you missed and hope to see you in Maine next year! Continue reading “Everything’s Better Down Where It’s Wetter: Benthic Ecology Meeting 2015”

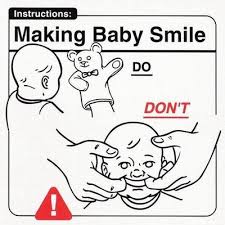

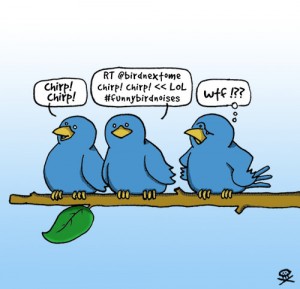

DOs and DO NOTs of moderation

Moderation is the art of “avoidance of extremes in one’s actions, beliefs, or habits”, according to dictionaries. In academic meetings chances are to find a colorful mix of extremes ranging from big mouths to shy introverts, and making everyone’s voice heard can be quite challenging. In worst-case scenarios, even hearing one’s own voice can become problematic.

Moderation is the art of “avoidance of extremes in one’s actions, beliefs, or habits”, according to dictionaries. In academic meetings chances are to find a colorful mix of extremes ranging from big mouths to shy introverts, and making everyone’s voice heard can be quite challenging. In worst-case scenarios, even hearing one’s own voice can become problematic.

In order to make a group discussion productive, smooth and -why not? – fun, participants designate or invite a moderator to fill in the conductor’s role. He or she will have excellent people skills and professional knowledge, will know how to puck the right strings and will seek to achieve group consensus in the most timely and efficient manner. One step ahead of everyone in the group, the moderator will be able to lead the discussion to fertile grounds where every participant is given the opportunity to produce its best.

But there is something more about moderation. A group discussion also resembles a cogwheel: each piece, big and small, make the big machine move. The interesting part however is never the individual piece, no matter how big or small (mouth he or she is), but the whole machine: the final, shiny product ready to roll. These are group synergies produced by the group’s dynamic, which are the most important outcomes of an academic gathering. The essence of moderation therefore revolves around catching and following the group dynamic.

Importantly, just like a good conductor, the moderator should never try playing and conducting in the same time. Even saying it sounds confusing. The moderator has a far more important active job to do than playing. At the end of the meeting, there are one, two or three work objectives that have to be successfully, and thoroughly, met.

Scary as it may sound at first, you might have already pictured yourself in the moderator’s shoes. Question is: are you a natural born moderator? Maybe you already know the answer is yes. Alternatively, perhaps you just need a little more practice, like I do. You don’t know the moderator hiding in yourself until you haven’t tried it.

My supervisor asked me to moderate an Ignite Session discussion at the Ecology Society of America 2014 meeting in California. Cautiously, she also suggested I should practice before, by moderating a group discussion about … moderation at a NERD club meeting at TCD. We gathered our ideas about what lies behind a successful moderation and what defines a successful moderator. I listed our thoughts in a cheat sheet below, where I contrast do’s and do not’s of moderation. Having it at hand can help you a great deal preparing for your first, second… however many moderation sessions you will lead.

At the Ignite Session in California, we had a houseful of people, and I only had to use about 5% of my moderator skills. We had questions flowing in for 45 minutes, after which we had to free the room and we moved the discussion closer to a couple of beers. Success! Phew, what an experience! I’m looking forward to the next one.

CLARITY DOs

State the topic, scope, objectives, expectations, rules at the very beginning

Speak up!

Make sure you repeat the audience’s questions so that everyone can hear.

Dig out your best communication skills

Be organized (have introduction, have end summary)

Be rigorous (keep people on track)

Keep it Simple! (simplify, reformulate, translate if necessary)

CLARITY DON’Ts

Ask long questions

Make confusing statements

Get confused and loose track

Get intimidated

PREPARATION DO’S

Have “conversation starters”, a list of questions

Have a global vision of the topic under discussion

Know your audience in advance

Get a hold of the logistics (microphone? assistants? co-moderator? recorder?)

But always be prepared for surprises, good and bad

Practice! Moderate a work group about … moderation!

PREPARATION DON’T’S

Be superficial, unprofessional

Not have a clue about your audience

COMMUNICATION DO’S

Build on previous questions

Ask clarifying questions

Get out of the “rabbit holes” (self-explanatory topics)

Yes, do interrupt “silverbacks” and “prima donnas” (speakers who like hearing themselves)

Have supportive attitude

Calm down spirits

Maneuver spotlights wisely

Make conscious effort to involve each participant to make individual decisions and take independent actions.

Be inspiring

Employ strategies such as group work, “Think, Pair, Share” or “Speed Dating” to engage audience

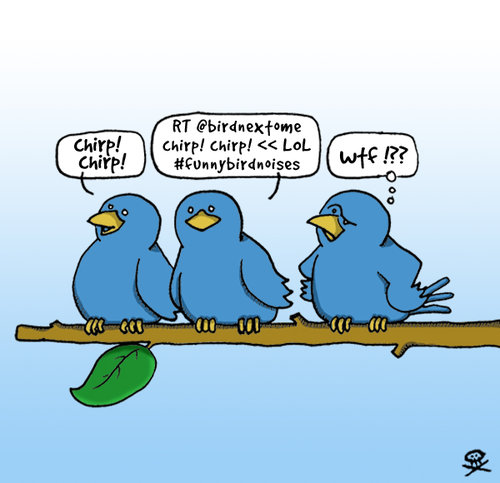

Redirect people to e.g. Twitter to ask additional clarifying questions

COMMUNICATION DONT’S

Ask closed questions (e.g., to which the answer is obvious)

Shut down speakers

Be cynical

Ask controversial questions that may take days to solve

Have judgmental attitude

Embarrass & Humiliate

Put people on the spot

Force consensus

NEUTRALITY DO’S

Be neutral, make others debate

Treat everyone equally, make voices be heard

Be respectful

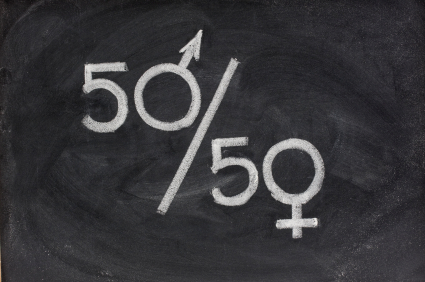

Pay attention to the gender balance

Keep the arguments balanced

NEUTRALITY DONT’S

Take sides

Engage in debates

Answer to provocative questions, argue

Express opinions

Participate in discussions

Share own views

EFFICIENCY DO’S

Be exact & short

Ask the right questions

Focus on the process no matter what

Have an excellent time management

Tackle not more than 3 broad topics

Persevere

Keep discussion alive

Use beeper if necessary to stop a speaker or close a topic and get to the next

EFFICIENCY DONT’S

Chit-chat

Ask meaningless questions

Make the discussion an endless story or soap opera

Ask “pressure mine” questions (put discussion on sidetrack)

Overstuff schedule

FOCUSED DO’S

Pay the highest level of attention

Practice the ability to think two things at the same time (current discussion & next questions)

Be quick witted

Hear everything

Keep track of the discussion

FOCUSED DONT’S

Get distracted, loose track

Get lost in details

Get lost in “rabbit holes” (shallow discussions)

ORGANISATION DO’S

To be able to synthesize, take notes along

Summarize periodically (at least provide a mid-summary)

Provide end summary

ORGANISATION DONT’S

Let the discussion flow endlessly

Loose audience

Loose end and scope

PERSONALITY DO’S

Be dynamic (follow the group dynamic)

Be flexible (do not stick to your pre-prepared questions)

Be creative!

Use your sense of humor

Be confident!

Be engaging!

PERSONALITY DONT’S

Be melancholic and sad

Be tired and depressed

Be bored

Be narrow-minded

Be rigid

Remember:

- Moderation is an art, you need to use both people skills and professional knowledge.

- The success of a discussion depends on how well prepared and competent you as a moderator are.

- It is a very good idea to follow the group dynamic and obtain group synergies.

Author: Ana Maria Csergo, csergoa[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: Safe Baby Handling Tips

Size isn’t everything: organising small conferences

The late afternoon sky drizzled softly on Manchester. The pubs along Oxford Road gently creaked with the weight of workers sinking pints following a long week of doing whatever it is that people who work in Manchester do. Sat in a beer garden, I relaxed and pondered the exceptionally busy previous 48 hours, the main feature of which had been the effective and successful running of a small conference. Having waved goodbye to 50 happy delegates, I had the time to reflect on what had made it successful.

The small conference in question was a joint meeting of two British Ecological Society special interest groups: Plants-Soils-Ecosystems and the Plant Environmental Physiology Group. Entitled ‘Carbon Cycling: from Plants to Ecosystems’, with its own snappy hashtag for the social media savvy (#psepepg), the conference took place over two days, attracted around 55 delegates, and featured three keynote speakers, 21 talks and 10 posters. After a lead-up lasting months, the two days of talking, problem-solving networking, coffee-drinking and chaperoning passed in a flash. My co-organisers, Ellen Fry, Sarah Pierce and I (I should emphasise that Ellen and Sarah did all of the really tricky bits of the organisation, like dealing with the budget and organising space and food), have received lots of positive feedback about the meeting since.

Lots of our delegates said that they’d liked the inclusive nature of the meeting. Its small size and demographic, comprised of many PhD students and early-career researchers with a generous smattering of more senior academics, meant delegates could be confident of having a chance to speak to everyone over the coffee breaks and lunches. With just 21 talks, we could be generous with coffee breaks, providing plenty of opportunities for people to chat and particularly for early-career researchers to interact with our keynote speakers. The format worked well and had been tested previously, at a similar meeting last year; it was helpful to have Sarah on the organising committee, because she’d co-organised that conference. Another important issue is access for disabled delegates – something that we probably didn’t address well enough and will certainly be higher up the agenda next time.

There as little I could do ‘on the ground’ (jobs like scoping out the rooms, organising poster boards, booking the food) from Dublin, so I contributed by promoting the conference on social media and various email lists, and designing the abstract submission process and programme booklet. Google Forms provided a straightforward, free method for collecting abstracts online: each response on the form was sent to a Google Docs spreadsheet, making it very easy to keep track of abstracts and, importantly, difficult to lose them. All the abstracts were in one place and in roughly the same format, ready to slot into the programme booklet. The only stressful element of the process was that, with a week to go, we’d still only received a handful of abstracts, mostly for posters – cue more frantic promotion! Of course, everyone submitted their abstracts on the last day before the deadline. We had a similar experience getting people to register for the conference, using Eventbrite – the deadline had to be extended several times. Academics, it seems, don’t like to commit (though I suspect a lot of the late additions were a result of summer holidays and fieldwork seasons – timing is important)! One thing to note is that, for many academics with families, travelling on a weekend is not an option.

So what are the perks of organising a small conference for the PhD student or early-career researcher?

- They’re relatively easy to set-up, particularly through a society like the British Ecological Society. There are lots of people with expertise who can help.

- You get lots of interaction, including taking the keynote speakers out for pre-conference beers, and of course chatting with all the delegates. It’s a great way of getting a snapshot of the research currently happening in your field.

- Providing you have people who are willing to help, the organisation need not take over your life, though it probably will for the couple of weeks prior to the conference. Bearing this in mind, as long as the meeting stays small, the benefits outweigh the temporary hassle, and it’ll look great on your CV.

What went well?

- Everybody came – we had no drop-outs, and one person came all the way from the USA!

- We included panel discussions at the end of each four talk session, and these worked surprisingly well – I think the inclusive atmosphere at the meeting contributed to this.

- As well as three organisers, we had enough unofficial helpers, in the form of PhD students and post-docs at the University of Manchester, who could be roped in to help out with running the registration desk and shepherding delegates.

- Facilities existed for recording the talks, so we took advantage of this and put the talks online – a handy resource for people who couldn’t make it.

- Live-tweeting the conference, and packaging the tweets up afterwards as a curated Storify story, seemed to be popular.

What was difficult?

- Elements of the abstract submission / registration process were slightly fraught due to their last-minute nature. I’m glad that we allowed plenty of time for these: abstract submission two months in advance, registration one month in advance, and keynote speakers confirmed three months in advance.

- Getting the food right turned out to be a nightmare for Ellen, who had to do battle with the catering department. It’s worth thinking about the format of food you’d like people to eat – something that is quick to dish out and mobile is best for interaction.

- Although the venue was generally excellent, there was one stumbling block in the form of a door between the auditorium and the posters / food that could only be opened by certain people, which lead to a lot of ferrying delegates to and fro.

- A broken-down train on the morning of the second day prevented some of our delegates from arriving on time, but luckily we were able to shuffle the schedule around so that nobody missed their chance to present.

Organising small conferences can be exhausting, but it’s also great fun and a very good way of meeting lots of people and broadening / deepening your network. I thoroughly recommend it!

Author: Mike Whitfield, michael.whitfield[at]tcd.ie

This post also appears on Mike Whitfield’s blog.

Photo credit: flickr/uelwebteam, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence

Learning the art of conferencing

The start of the new academic year marks the end of my second conference season. I attended two conferences; Evolution 2014 in Raleigh, North Carolina and the British Ecological Society Macroecology meeting at the University of Nottingham. They were at the opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of size and specificity but they were both interesting, useful and, most surprisingly for me, enjoyable.

The difference is that I knew what to expect. Last summer was my first taste of conferences along with the intellectual and social stamina required to last through a day of talks, coffee breaks, poster sessions and post-conference socialising. I was very lucky that I went to each event as part of a group, so there was always a familiar face to find in a crowd and it made networking easier but I still found the whole experience challenging.

This time around was different; the familiarity made everything easier. For a start, I finally figured out how to plan a sensible schedule which didn’t involve running from one room to another between talks. Most importantly, I’m learning how to “play the game”. I’m slowly figuring out how to give an elevator pitch about my research without making the recipient’s eyes glaze-over and how to talk to other people about their research without sounding like a complete idiot. I’m still a long way off from being a proper conference pro but I’m getting there.

Giving a talk instead of a poster made a huge difference. Last year I brought the same poster to two different conferences. Through the course of each poster session, I spoke to a handful of people, some of whom seemed at least partly interested in my research but mostly they were being nice to the student with no one else at her poster. The experience definitely made me into a more pro-active browser at other poster sessions. People usually appreciate some interaction and it’s always more interesting to talk to someone about their research, even if it’s completely outside my area, instead of just admiring their poster design skills.

This year I gave a short talk at both the conferences I attended. It was nerve-wracking but definitely much more beneficial for my research and also my conference experience. I was lucky to have some useful preparation: we’ve often covered presentation skills in NERD club and I benefited from great constructive criticism during practice talks, especially from Thomas and Natalie who could probably have delivered my talk word for word by the time of the conference! It was worth the effort. My presentation was not ground-breaking in terms of the science content or delivery but I was pleased with how my talks went at both conferences. It was also very beneficial to get the feedback, comments and suggestions from the people in the audience who spoke to me afterwards. You get a lot more feedback after telling an audience your research “story” for 10 minutes rather than hoping to attract passers-by to a poster. Furthermore, at a small conference like the macroecology BES group, giving a talk helped to identify me as the “tenrec girl” so I could speed past the normal elevator pitch opening which marks most initial conference conversations.

Some people take to conferences easily; others have to work a bit more. If you’re part of the latter group then I can assure you that everything becomes easier and more enjoyable with a bit of familiarity, practice and experience. I still have a lot to learn but I’m getting there. I’ve realised that many people, particularly the more junior researchers, also find it tricky to master the art of conferencing. So if you’re feeling awkward standing around the coffee counter or sitting in a seminar on your own, chances are that the person next to you is in the same boat and you will both be happier if someone takes the first plunge into conversation. You will add another name to your list of friendly faces in the crowd or maybe meet a new collaborator. In any case, you’ve got nothing to lose so give it a go!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Gender balanced conferences – we all need to try harder!

Recently a conference on Phylogenetic Comparative Methods was advertised online, and quickly the Twitter community noted that all six of the plenary talks were being given by men. Normally my response to this kind of thing would be some grumpy tweeting and then I’d let it go. However, this time was different; I know one of the organisers, several of the plenary speakers are my collaborators and this is the field I’ve dedicated the last eight years of my career to. Therefore I didn’t think I could let this pass by unchallenged. Continue reading “Gender balanced conferences – we all need to try harder!”

We’re all going on a (science) summer holiday…

We’ve had another fantastic year at EcoEvo@TCD. We’ve published some high profile papers and brought back tales from our fieldwork experiences. We’ve learned how to navigate some of the perils of academia and thoroughly enjoyed hosting an excellent series of seminar speakers.

Now EcoEvo@TCD will be taking a short break over the summer so we won’t be updating the blog over July and August. We’re currently in the midst of another conference season, presenting our research at various international meetings and learning about the latest cool scientific research. Add that to some exciting travels and summer science projects and we’ll have plenty of stories to tell.

When we get back we’ll report on the highlights of conference season and bring you more ecology and evolution related news, views and advice.

We hope you have a wonderful summer. See you in September!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: pixabay.com

How to get the benefits of mobility – even when your movement is constrained

There are a long list of reasons why mobility in an academic career is considered highly desirable, both by individuals and the institutions which fund them. Scientists move around to take up jobs in a tight and international job market, communicate their work to the wider scientific community, work with new people, learn new techniques, strengthen networks or because they like adventure. However, there are many excellent scientists who are constrained in various ways to be less mobile than they would like or than would be good for their careers .

I have always loved to travel, and after almost 15 years of moving around for jobs, fieldwork, conferences and adventure, my own constraints arrived in the guise of two adorable children. My kids have taught me a lot about the benefits of a more sedentary life but I still have itchy feet and the desire to interact with colleagues internationally. This period in my life led me for the first time to really think about what it is about mobility that is of benefit and how to achieve that while staying at home.

Constraints are costly. Some constraints can be overcome by providing resources or altering institutional structures. Other constraints are personal or philosophical and might best be considered as hard constraints (unchangeable). Common constraints include personal family situation such as partner’s career and caring responsibilities for children, parents or friends and personal mental and physical health. The costs of mobility include financial costs, disruption, adaptation to a new scientific and/or social culture, language barriers and leaving a productive group. For all of these reasons scientists may be temporarily or permanently constrained from being able to physically move locations for work reasons.

It makes sense to me to have a range of strategies for getting the benefits while minimizing the costs of mobility. Grant applications sometimes explicitly or implicitly require or evaluate mobility as a proxy for the benefits obtained. If you have had your mobility constrained it might be useful for you in grant applications to articulate what strategies you have used to get the benefits of mobility despite your constraints.

First determine exactly what your constraints are and exactly what activities are constrained. For example do you care for young children which prevents you from traveling overnight for a period of time? Do you need to be in close proximity to healthcare? Determine the boundaries of your constraints. Next estimate the benefits of mobility to your particular situation – the benefits of mobility might be largest if you are currently in a small, relatively unproductive group with limited resources and the benefits of mobility might be much smaller if you are already in a large, productive, well connected (lots of incoming visitors) group.

Determine the costs of mobility: financial, social, environmental and to your productivity. Costs may be larger as you progress through your career but are also more likely to be defrayed through relocation expenses paid or broader networks of colleagues gained. Perhaps for you the costs outweigh the benefits as you are already in the ideal group and don’t want to move because it’s working extremely well for you. Great, but be open minded about additional opportunities to gain additional benefits at low cost.

It is important to recognize that a case for gaining the benefits of mobility may be easier to make with a broad view of mobility. Mobility can be short- or long-term and can be inter-institutional, cross-sectoral, national, international or intercontinental in scale. Many benefits could be gained from doing internships in a different institution or industry but remaining in the same city for example. Below are a few strategies that might be helpful, not all will be possible depending on your situation.

Find a position in a group in your location which is large, productive & well connected. You don’t necessarily have to be employed by them if you can negotiate a day or two a week as a visitor there.

Make use of technology for virtual collaboration – Skype, Adobe Connect, Google hangouts, dropbox, telephone, email, twitter, blogs, Mendeley, Git etc. These require a bit of work to ensure efficacy and avoid the “out of sight, out of mind” problem of not bumping into collaborators in the hallway.

Attend meetings in virtual mode by accepting to give talks but ask to be able to give a video presentation, this is most effective if you can also take part in the discussion afterwards via video conferencing. Ask the organisers to record and send you the video afterwards so you can re-use it. Use twitter to keep up with what’s happening at the meeting if you can’t attend. Tweet and/or blog for others if you can attend in person. I was immensely grateful for the tweeters and bloggers when I was at home on maternity leave and couldn’t attend “my” meetings for a few years.

Attend conferences and extend your network, make sure you gain active collaboration from conference meetings. Be part of international working groups, engage or initiate global research networks.

Develop relationships with potential collaborators via social media, name recognition is important and people will be more inclined to work with you if they have interacted with you positively via twitter/facebook/whatever young people do these days.

Invite visitors to your institution. Find out if there are funds available to help visitors pay for their visit (e.g. visiting fellowships, travel funds if they give a seminar), help visitors apply for these. Paying for a few extra days of accommodation for a visitor if their flight is already covered can be a cost effective way to encourage more interaction. Offer to let them stay at your house. Parasitise sabbatical visitors to other close-by institutions by inviting them to your institution for a day/week/month.

Apply for grants to fund workshops which enable you to run working groups at your own institution and which fund the travel & accommodation of visitors.

If you get invited to present or visit and can’t do it, ask if you can send your student/post-doc/colleague in your place. Make sure you follow up with your proxy to ensure you learn what they’ve learned and if there are outputs of the visit that you can also contribute to.

Lobby funding organisations and institutions to allow your mobility constraints to be taken into account in funding applications and promotion cases (e.g. caring for family members).

Lobby funding bodies and employers to directly fund expenses associated with travel (e.g. extra care for dependents).

Record on your portfolio all invitations to speak/present/take part, even if you have to turn them down as these are useful indicators of your profile and measures of esteem.

Be creative in finding ways to relax your constraints, perhaps you can pay for a grandparent to travel and accompany you on a conference trip as extra child support, perhaps you can take your baby with you to the conference and rely on them to stay quiet enough for you to give a talk with them asleep in a sling, or pass them onto trusted colleagues willing to babysit for half an hour. I took my 2 month old to a workshop, pictured here with Antoine Guisan, where she got passed around several academic alloparents to enable me to contribute to this paper. Perhaps you can afford extra childcare by living frugally while travelling. Be flexible.

Ask conference organisers to make provisions if you need to bring your kid/s with you. For example have a family room with the talks screened via video-conferencing/skype or provide crèche facilities.

Discuss with your partner possibilities for one or both of you to take up part-time work or for your partner to become primary home carer. Move closer to extended family, especially if they are willing to help with caring responsibilities.

Finally, for funders, conference organisers and others who rely on the ability and willingness of scientists to pack their bags and jump on a plane at a moment’s notice, spare a thought for those who are constrained. Provide alternative arrangements for child-care at meetings, provide opportunities for video conferencing, encourage participation and consider evaluating CVs based on what benefits have been gained, not just how many times someone has moved.

Author: Yvonne Buckley, buckleyy[at]tcd.ie, @y_buckley

Presentation tips: how to create and deliver an effective talk

Off the back of our recent Postgraduate Symposium, I thought it would be useful to summarise some of the advice and criticism we received afterwards. These points are a mix of the feedback from our invited speakers, academic staff and fellow postgraduate students, as well as some of my own observations and preferences. While the majority of the information below is common knowledge and most people do their best to give a good talk, the reality is that there is no such thing as a perfect talk and there will always be room for improvement; that’s fine! Just do your best and afterwards take note of what areas you would like to improve.

1) Remember: slides are an aid to your talk, they are not the focus. Your voice should be the primary focus of the audience; the accompanying slides are to help you explain more complicated ideas and results, introduce a study system or area and generally keep your audience interested (hence the inclusion of many an interesting/pretty/grotesque picture). Therefore, in general, you do not need large sections of text on your slides. As much as you may think the text is necessary, it most likely isn’t so get rid of it! This removes any temptation to read off the slides and helps keep your audience focussed on you. Furthermore, you are more likely to give a better talk with a more natural flow if you stick to this. The most informative and enjoyable talks I have seen typically contain slides with almost no text, primarily using figures, photos, cartoons etc. Also, don’t go for overkill and try to say too much. Present a concise, clear and fluid story for your audience to follow, leaving out any gritty methodological and statistical details that are not central to your research.

2) Talk to the audience – all of it – and never to your slides. This means that you always face your audience, regularly changing the direction of your gaze, speaking loudly, slowly and clearly, therefore engaging as much of the audience as possible. Furthermore, when you are presenting to an international audience, remember that English (or whatever language you are speaking) may not be the first language of many attendees. This is when it is even more important to make an effort to speak loudly, clearly and slowly (and avoid using any slang).

3) Enjoy yourself! Do your best to smile, relax and be enthusiastic about your research. Unlike a typical manuscript, a presentation allows you to inject some passion for your work. If you are not engaged or enthused, how do you expect your audience to be?

4) Always remember to state the general importance of your research and what areas it applies to. Make your research and topic as relevant to as many people as possible (within sensible limits, of course). This is sadly overlooked by many postgraduate students and can be frustrating to watch. You can do this (i) at the beginning by starting with a broad introduction (this does not equate to five slides of background information, rather it could simply be a few sentences, just to provide your audience with a context) and (ii) at the very end, discussing the implications of your results to your field as a whole, addressing the scope of the symposium/conference/session if particularly appropriate.

5) If a particular aspect of your work is complex and difficult to explain, do your best to deconstruct it with the relevant figures and always repeat the main point/finding before proceeding.

6) Always handle questions in a polite, interested and engaging way. Be open, not defensive. A good tip is to repeat each question for the audience so that they all hear it. While this keeps all of the audience clued in, it also gives you time to formulate a response in your head. When you respond, remember to address all of the audience, not only the ‘questioner’, and always mention that you’re happy to discuss things further afterwards (I’d go as far as encouraging people to come chat to me afterwards, even if it is just to grill me; a grilling is always welcome as a postgrad!).

7) Dress for the occasion. Be comfortable but also mindful of why you are giving a talk and who you are giving it to.

8) If you are using a laser-pointer, avoid waving it around excessively on the screen. Use it sparingly, only when a particular detail needs highlighting.

9) Always check the compatibility of your files, allowing time to make amendments if needed, save in multiple formats and have back-ups, whether on another storage device or in your email inbox.

10) Learn from other presentations what aspects you particularly like and dislike. For example, I prefer when acknowledgements come at the start of start of a talk as this allows the speaker to finish with a focussed, ‘take-home’ message of the research. Also, you don’t need to read out every name in your acknowledgements; people will always do it themselves so just go for the major ones.

11) Practice your talk multiple times aloud (how it sounds inside your head does not equate to how it actually comes out).

12) Finally, don’t panic; be confident and do your best.

Author: Seán Kelly, kellys17[at]tcd.ie, @seankelly999

Image Source: phdcomics.com

Conference season madness!

Over the last month or so you’ll probably have noticed that a lot of posts on EcoEvo@TCD are essentially “what I did on my summer holidays” essays. Luckily, I think most of us did quite a lot of interesting and scientifically relevant things! My summer this year seemed to be full of conferences, so I thought I’d write a quick post describing them, and what I liked or disliked. This post was inspired by Britt Koskella’s excellent post on the same subject; although Britt attended NINE conferences this summer so is clearly completely insane.

Over the summer I attended four international conferences: Evolution 2013 in Utah, BES Macroecology in Sheffield, International Mammalogical Congress in Belfast, and ESEB 2013 in Lisbon. This involved 15 days of conference going, four plenaries, one prize talk, eight invited talks, 103 standard talks, and 56 lightning talks. So in total I spent about 40 hours in talks, not including questions or people running over time…

Evolution 2013, attended by around 1500 people, was in late June, and was probably my favourite conference academically. I’ve been going to Evolution since 2006 and have only missed three meetings in that time, so it’s the conference I know the most people at, and is most closely aligned with my interests in macroevolution. Most of the top names in the field were there, and I saw some excellent talks. I particularly enjoyed the plenaries. Richard Lenski’s plenary reviewed 25 years of experimental evolution using E.coli in his lab, Dolph Schluter’s discussed ecological opportunity as a factor in increasing rates of diversification, and Jack Sullivan talked about advances in systematics since the last meeting at Snowbird (although this talk was mainly notable for the “dirty chipmunk sex” and pictures of ground squirrel bacula – look them up on Google!). The plenaries at Evolution are generally entertaining and thought provoking, and in recent years there seems to be a trend to talk about something controversial. This is great and I think that’s how plenaries should be! The other big highlight was the location. It was up in the ski resort of Snowbird at 8,000 feet, so we were surrounded by snowy mountains, cheeky ground squirrels, marmots and even the occasional moose. On the flip side, this year’s Evolution was smaller than usual (or felt smaller) because fewer European scientists made the trip. With ESEB (the European equivalent of Evolution) and INTECOL happening in August many people decided to attend these instead. This made it feel a bit more US-centric than usual.

My second conference of the summer happened two days after I got back from Utah and was in the less exciting location of Sheffield (sorry Sheffield, you just don’t have enough moose). This was a much smaller conference with only 60 attendees. The great thing about this was that I was able to briefly chat to almost everyone at the conference. In addition, many of the attendees are old friends of mine so it was lovely to catch up with them. This was a British Ecological Society special interest group meeting on Macroecology (if you’re UK or Ireland based I’d definitely recommend checking out any of the BES special interest groups, they’re friendly and full of enthusiastic people!). We spent the two day meeting listening to five minute talks from anyone who wanted to present, then had panel discussions after the talks which worked really well. We also had some “break out” groups to discuss the future of the field. The most interesting of these for me was – “If we got £20 million from the government today what would we spend it on?” Amusingly this mostly boiled down to people wanting more, and better quality, data! The highlight of this meeting for most people was Ethan White’s excellent plenary. I’m sure it would have been mine too but I had issues with my train and ended up being two hours late and missing his talk (sorry Ethan!). The train also “ate my homework” (I had to stand all the way on the later train so didn’t get chance to write my talk). I promise to do better next year!

My third conference was the 11th International Mammalogical Congress in Belfast. Full disclosure – I’m not really a mammalogist (I work on mammals, but just because the data is good) so this was an odd one for me. But Belfast is only two hours away on the train and my PhD students thought it would be fun to present their posters more than once. Organisationally this was a strange conference (no offence intended). The talk program wasn’t online so there was a lot of frantic flipping through the booklet to try and find talks. There had also been a change to the program that removed the second poster session, meaning that one of my students turned up a day late to present his poster. However, I saw some really interesting talks, particularly in the disease ecology symposium. I also saw the worst set of PowerPoint slides I’ve seen in a long time – lemon yellow background, brown text with shadows, no pictures and text completely covering each slide! Yeurgh!

My final conference of the summer was ESEB 2013. This was a lot of fun and I saw some excellent talks. I also discovered that I don’t understand population genetics. At all. I think by this point I was “conferenced-out” so it was a difficult conference for me. Also because of the overlap between INTECOL and ESEB, a lot of people I would normally catch up with there were at INTECOL instead. This was particularly reflected by the paucity of macroevolution talks and attendees with macroevolutionary interests. In fact, our delegation (myself and five students) from TCD was probably the biggest group of macro-people there! This meant there were a few days where I found it hard to find many relevant talks. I still attended some very interesting talks, but I also spent a lot of time feeling very stupid because I attended lots of talks I didn’t understand at all! The highlight of this conference for me (partly due to my macroevolutionary interests, partly due to my love of pretty slides) was Rich FitzJohn’s JMS prize talk. The content was good but the slides (all made in R apparently!) were gorgeous. I also really enjoyed Hannah Kokko’s talk where she was able to describe quite complex maths in a really accessible way. The other, less academic, highlight was tweeting a picture of some Superbock – a local beer – and the beer company replying, thus ruining the conference twitter feed by filling it with pictures of beer! Oops!

My conclusions:

1)Four conferences in a summer was too many conferences! Each was fun in it’s own way, but conferences are exhausting both mentally and physically (often talks start early and social events end late) so I ended up feeling totally wiped out for weeks afterwards. Next year I think I’ll focus on two or three at most.

2)Feeling stupid at a conference is inevitable at some point, but it doesn’t mean that you are stupid. When I was a PhD student I felt stupid all the time, but as I’ve become more seasoned I’ve realized that often it’s because the speaker isn’t explaining themselves properly, or because it’s so far out of my field that I don’t know the background. If you don’t understand, try and discuss it with others afterwards. We’ve been doing this a lot after seminars recently and it’s really helped my understanding of the trickier bits.

3)Big conferences are great for meeting lots of people you know already, but terrible for making new connections. From now on I’ll try and go to one big conference a year to catch up with old friends, and one small conference where I can meet new people.

4)Going to four conferences made me realize how cliquey a lot of evolutionary biology is. Many of the people speaking in symposia had also spoken at symposia in previous years. In some cases people spoke in symposia at multiple conferences (and gave almost the same talks). This is inevitable to some extent and shows the importance of having a good network within your subject. Next year however, instead of moaning I’m going to organize my own symposium and try to invite some people I don’t know, plus women and early career researchers. I’m also going to make more of an effort to attend small conferences where I don’t know lots of people.

5)Twitter is an awesome way to improve your conference experience (see my other blog posts on this). But don’t tweet too many pictures of Superbock…

Author: Natalie Cooper, ncooper[at]tcd.ie, @nhcooper123

To tweet or not to tweet, that is the question…

This August I celebrated one year of being on Twitter. On the auspicious occasion of my Twitter-versary I decided it might be useful to reflect on the year. Did I get what I wanted to get out of the experience? Did I get other things I didn’t expect? Or did I just find myself an amazing way to waste a lot of time? Should I continue my affair with the Twitter-verse? (SPOILER ALERT – I’m obsessed with Twitter so of course the answer is an emphatic yes!)

What did I want to get out of the Twitter experience?

For some reason TCD doesn’t have much of an international reputation in Ecology and Evolution, despite a strong record in publishing papers in the area. In fact, when I started working here in January 2012 a lot of people were surprised that TCD had science departments! Clearly this needed to be fixed if we were going to attract high quality students and postdocs to our groups. A couple of my friends had been raving about Twitter for a while so I decided to give it a go. I also convinced Andrew Jackson to start actively using his account and over the course of the year we’ve got most of the ecology and evolution postgrads and staff on Twitter as well. The overall aim was a mixture of selfish self-promotion, and slightly more altruistic promotion of the School of Natural Sciences and our research.

Did I get what I wanted from Twitter?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot and surprisingly I don’t think I did (carry on reading below for some unexpected benefits which totally outweigh this “failure”). This is mainly because I had really unrealistic expectations of what Twitter was going to do. I had visions of hordes of potential students and postdocs contacting me. However, the reality is that, at present, I have not had anyone contact me via Twitter looking for PhD or postdoc funding opportunities. When we advertised a Chair in our department I don’t think anyone who applied saw the advert on Twitter. However, I do think some of these things will happen in time. It’s important to remember that building a Twitter following requires effort and takes a long time. It’s also really hit and miss – sometimes a tweet will get loads of retweets and replies but a similar tweet will be left to float into a black hole of nothingness. And sometimes no-one comments but everyone reads your tweet and remembers it. So it’s pretty impossible to gauge your impact.

In the interests of honesty, there are also a few other downsides to Twitter that I’ve outlined below.

Downsides I: The echo-chamber effect

This has been mentioned by lots of people, but essentially you follow people with similar opinions to yours, and vice versa. So you only see tweets from people with these similar opinions leading you to believe everyone agrees with you. I have a simple way to remind myself that this isn’t the case. Every now and then I’ll look at what’s trending in Dublin/Ireland/globally. Five minutes reading tweets about Harry Stiles from One Direction (“He’s a cupcake not a man-whore!”) are more than enough to remind me that not everyone in the world thinks about things like I do.

Downsides II: Negative tendencies

I’m not sure if this is a trait common to all scientists, or if it’s that Twitter breeds gloom, but there is a lot of negativity about academia on Twitter. Mostly this revolves around the difficulties of getting a permanent academic position, the problems of being a woman or a minority, issues with scarcity of funding, or general gripes about writing up your PhD thesis. All of these problems are real and frustrating, and it’s great to vent about them from time to time. However, if you’re already miserable then reading a whole load of negative comments can sometimes make you feel even worse. I think this is generally balanced by the other more positive aspects of Twitter but I do sometimes unfollow the most gloomy people! This leads me on to the unexpected benefits of Twitter.

Unexpected benefits I – Support

As I mentioned above, people often use Twitter to vent about the bad aspects of academia. The great thing is that when you do this there’s always a couple of people there to make you feel better, and like you’re not alone. Generally these people don’t know you personally, so it’s just a nice altruistic outpouring of support. On the flip side, when things go well people are also ready to congratulate you and encourage you. This is a wonderful and totally unexpected benefit of using Twitter! I’ve also had the great pleasure of meeting many of my Twitter friends in person recently. These are often people completely outside my area of research but they totally delightful human beings to hang out with (even if it’s extremely odd to talk to them rather than keeping it to 140 character messages).

Unexpected benefits II – Radically improved conference experiences

I enjoy conferences, but using Twitter has catapulted them into a whole new level of usefulness and enjoyment. Even just passively reading Twitter feeds during conferences I’m not attending is fascinating, and a great way to keep up with fields I’m interested in when I can’t attend the conference. When I’m at a conference, I find live tweeting really helpful for keeping myself alert and engaged in the talks, it’s an excellent way to keep notes and it allows you to interact with people who aren’t at the conference or to discuss talks with people at the conference even as the talk is being given. I also really enjoy meeting other Twitter-ers (is that a word?!) in person. This is particularly useful at conferences where I don’t know many people.

Unexpected benefits III – Resources

I already wrote a blog about the ways you can use Twitter to save time so I won’t repeat it here, but basically I’ve found links on Twitter to everything from newly published and relevant papers, statistical tests I need for my research, information on hot topics in academia, conferences, funding opportunities, resources for students etc. My students have also used it to get advice on their PhDs and side projects.

Unexpected benefits IV – Funny animals to ease the troubled mind.

Finally, if you’re ever down, avoid the gloom-mongers and look for people posting GIFs, videos or pictures of funny animals. There are few levels of gloom that cannot be alleviated by a video of animals using trampolines or my personal favourite, animals fitting into tiny spaces.

So in conclusion I think the benefits FAR outweigh the negatives of Twitter. If you haven’t tried it yet, have a go! If you have and I follow you, thank you, you’ve made my life a more interesting, engaging and hilarious animal-filled place.

Author

Natalie Cooper:ncooper[at]tcd.ie

@nhcooper123

Image source

www.binoyxj.com