My post on the problem of consciousness troubled a few readers because I dared toy with the idea of dualism, something so offensive to scientists I’m wary to speak its name. But I’m going to continue to argue for dualism because it’s not clear to me that it is wrong even for all the flack it has received. I think a return to this topic is also warranted because of the controversy generated by Thomas Nagel’s latest book, ‘Mind and Cosmos’.

A charge made against my previous post was that dualism is a pernicious idea. Yet nihilism is a negative, and I would argue, damaging philosophy par excellence, but that has no bearing on its truth or falsity. Similarly, one commentator spoke about dualism being argued for because it speaks to a human desire to be something more than physical. But, again, that does not mean it’s wrong. This holds for any idea. We can only take people to task in arguing for something if the only reason they do so is because it comports with their views.

(On a side note I reckon the implications of a physicalist universe are far more terrifying than a dualist one. They are best spelled out by the atheist philosopher Alexander Rosenberg in his essay ‘The Disenchanted Naturalist’s Guide to Reality’.)

Previously I used David Chalmers’ zombie argument to question if the world as we conceive it can account for the presence of consciousness. Chalmers summarises the message of his original zombie argument as “If any account of physical processes would apply equally well to a zombie world, it is hard to see how such an account can explain the existence of consciousness in our world.” Arguments from logical possibility are contentious but let’s not lose sight of what Chalmers is saying.

The subtitle of Nagel’s book is likely to grab the attention of biologists – ‘Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False’. But you should hold your cries of “Creationist!” because they’re misplaced. I really need to stress that this debate should not be framed as being between science and religion or science and pseudoscience but rather physicalism and dualism. Indeed some of the more prominent defenders of the latter position, Nagel and Chalmers included, are card carrying atheists.

I haven’t read Nagel’s book yet (I hope to do so) but you can get a sense of the themes he develops from the following description, “The modern materialist approach to life has conspicuously failed to explain such central mind-related features of our world as consciousness, intentionality, meaning, and value.” He argues that there is something more needed to get us from physical matter to conscious thoughts, not even evolution by natural selection can get us there with a purely material world to manipulate. There is a difference of kind rather than degree here.

Some of the criticisms of his latest work argue that he leaves a lot unsaid and many of his arguments have been criticised as vague. But Nagel is most famously known for a famous 1974 essay he wrote on ‘What Is it Like to Be a Bat?’ He says that although bats are conscious they experience the world in an entirely different way to us i.e. there is something like it is to be a bat. If we imagine ourselves as being bats it’s actually through our human minds, i.e. we’re imagining what it would be like for us to have echolocation, which is entirely different. If instead we record all the sensory data that a bat experiences we’re still left wondering about how he/she experiences the world from its own point of view. The normal physicalist approach leaves us guessing.

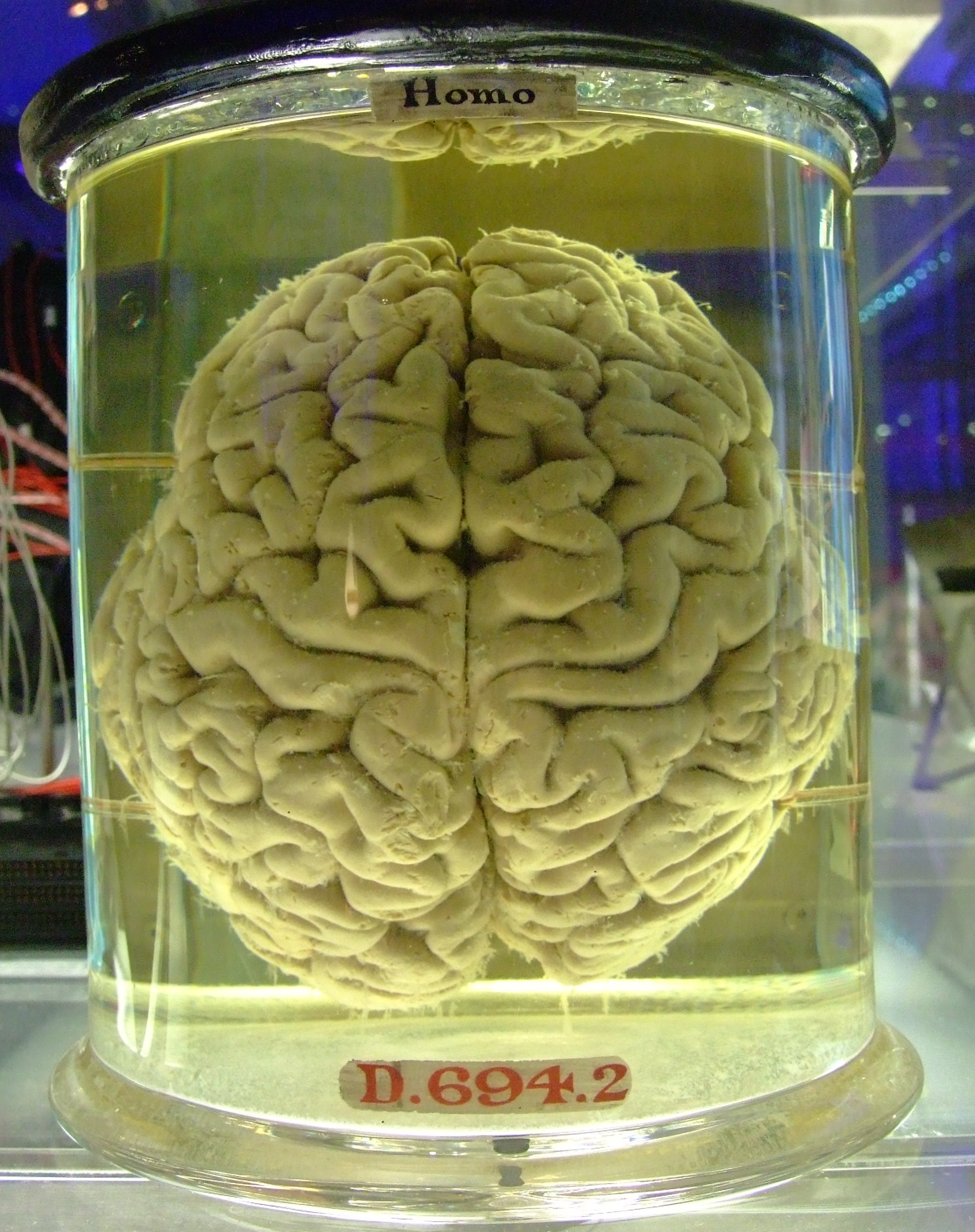

Previously we were asked to have a prior commitment to physicalism but there are a number of properties of consciousness that should cause us to at least re-evaluate our priors. Neurons, physical entities that they are, do not seem to have the tools to do what is being asked of them. When it comes to physicalism, past performance is no guarantee of future success.

Author

Adam Kane: kanead [at] tcd.ie

Photo credit

Worldprints.com