Part of our series of posts by final-year undergraduate students for their Research Comprehension module. Students write blogs inspired by guest lecturers in our Evolutionary Biology and Ecology seminar series in the School of Natural Sciences.

This week; views from Dermot McMorrough and Maura Judge on James McInerney’s seminar, The hybrid nature of eukaryotes rejects the three-domains hypothesis of life on Earth.

Time to stop the press? Science for the Masses.

What exactly constitutes “pop science”? What is it that takes a piece of research from the relative anonymity of peer-reviewed journals and academic conferences to mainstream media outlets and the masses?

Dr James McInerney addressed a topic of monumental importance to the way we understand life on Earth. If his findings are accepted and withstand the test of time, we will actually have to rewrite biology textbooks around the world and that’s a pretty big deal. I must admit I was impressed with his claims, and he seemed incredibly thorough with how he went about proving them. At the end of his impressively complex and graphic filled presentation, I was left with one main question: why was I only hearing this now? His paper has been accepted by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (impact factor of 9.737), and has implications for almost every field of biology, so why isn’t this being shouted from the rooftops? My inner nerd wants answers and is feeling quite indignant at this stage.

After some thought and discussion, I think I’ve found my answer: People don’t care. My inner nerd has retired to the bar; it’s a harsh reality to take.

I was once told that information, not money, makes the world go around. While this is a romantic notion for someone fascinated by learning new things, that information is rarely free.

Science is often reported in mainstream media. People like to think they’re learning something new on their way to work, and so stories with a scientific undertone (and rarely more) are common in daily newspapers and in the general media pick and mix. These articles often do have scientific background, but have been so bastardised to make them more digestible that they are scantly recognisable as related to the original research. Recently, here in the department of Zoology, many of us were surprised to hear that our own Kevin Healy and Dr Andrew Jackson had become “fly experts” according to media outlets such as Today FM. How do you make the move from macroevolution and computer modelling to entomology and pest control overnight? You don’t. The media does that bit for you. The story needs to be easy to understand, and while the flicker fusion rate study was fascinating, it can be hard to grasp if you’re not familiar with the background. I’m not exactly happy with how this happens, but if it gets the scientists (who’s work so often goes unnoticed by the public) a bit of publicity, then it’s a price I think we’ll have to be willing to pay. Science is not immune to the realities of economics and so needs funding to survive. If a story about flies helps them get a grant to further their research in a field completely unrelated to entomology, so be it.

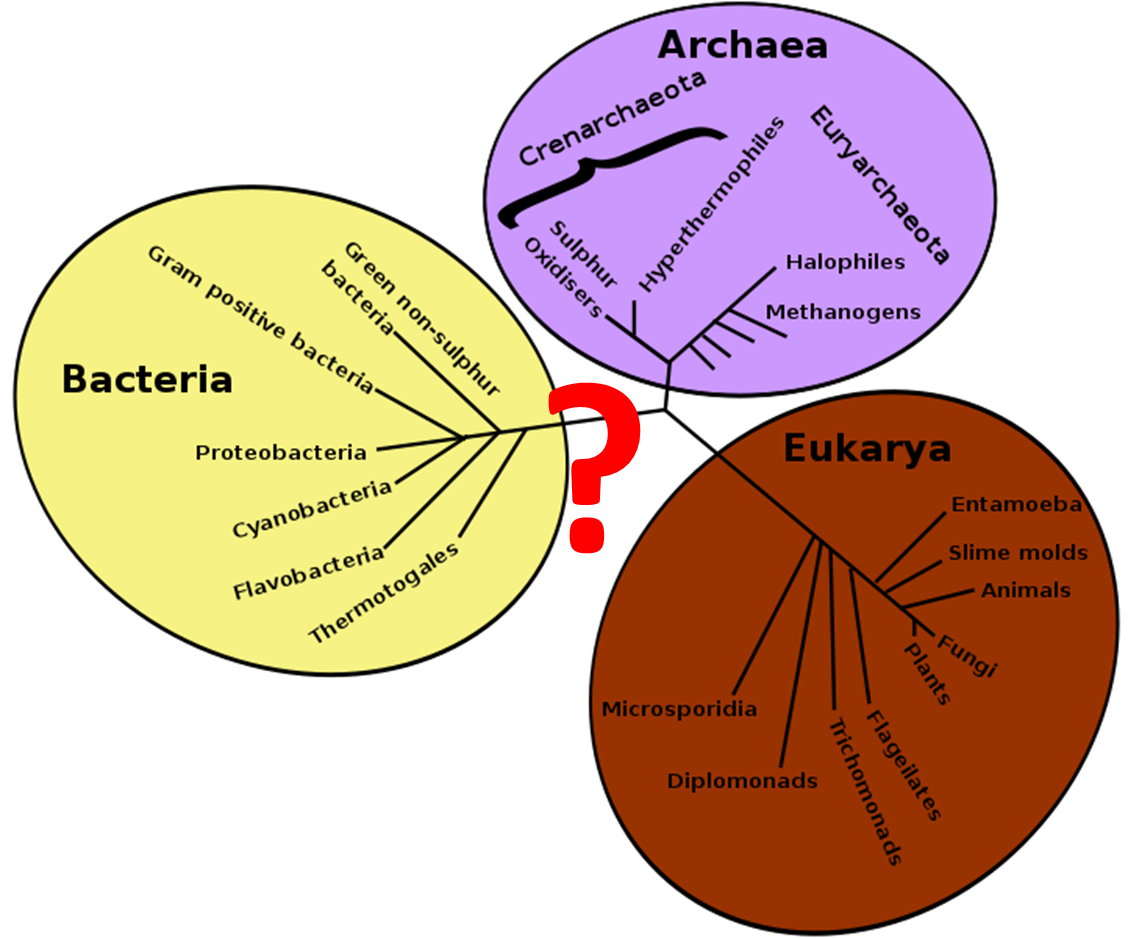

What has this got to do with the seminar? Dr McInerney just rewrote the book on the domains of life, not a species or a phylogeny or insects – the domains of life! Surely the people would want to know this right?

Science editors in news outlets will “dumb down” these stories as not to make their audience feel inadequate (who reads a newspaper to feel stupid?). The problem with the domains of life story is that dumbing it down could take a while – a long while. I’ve done 3 years of science, one of which supposedly specialises in this field and it took me a while and a lot of help to figure out how he was going about proving his claim. To get that story onto the front page of the Herald, you’re going to have to write very small and hope the average reader has a clue what a domain even is.

So can this story ever make it to the masses? It’s not going to be easy. For science to make the headlines, it usually has to involve the word cancer, obesity or global warming – either with the intention of condemning us for being fat, lazy death traps, or better still telling us we can cheat death a bit, while still being fat lazy death traps.

I was impressed with Dr McInerney’s talk, at least what I understood of it. I do, however, have one caveat before this is unleashed on the world. To change dogma such as the current domain hypothesis, you need to be able to explain it more or less in one sentence. People do not accept change like this lightly. I got the impression he struggled to get his explanation into a one-hour slot in a room full of undergrads and academics. If he can explain it in simple terms, he’s onto something. My inner nerd has hope yet.

Author:Dermott McMorrough

———————————————————————-

The seekers of truth?

As Richard Dawkins says in the selfish gene “those who choose to study it [Zoology] often make their decision without appreciating its profound philosophical significance”. I personally feel this statement could not be truer. After a debate regarding evolution the other week, a fellow classmate remarked “I just don’t like thinking about all those deeper questions”. Is this the right attitude? Einstein did not believe so. “When I think about the ablest students whom I have encountered in my teaching, that is, those who distinguish themselves by their independence of judgment and not merely their quick-wittedness, I can affirm that they had a vigorous interest in epistemology (branch of philosophy that studies knowledge)” (Einstein 1916).

In a seminar delivered by Professor James McInerney he asked the question of how complex life really began. He began his talk by highlighting the importance of philosophy and of past philosophers in his work. This idea intrigued me and I began to ask, are we neglecting this important link? Karl Popper, a German philosopher, wrote many books in the 1960s electrifying the scientific community. He said you are doing science if you can invent an experiment that proves yourself wrong. This idea is known as falsifiability and is sometimes synonymous to testability. As you can see, this idea of proposing and testing hypotheses in a way that allows you to reject them is in keeping with the modern day, highly relied upon, scientific method. Popper stressed the problem of demarcation, which is distinguishing science from non-science or pseudoscience and made falsifiability the demarcation criterion. This means that what is unfalsifiable is classified as unscientific. However there is a problem with this; evolutionary scientists cannot falsify their observations and hence even the theory of evolution is still only deemed a theory. Popper later amended this, saying you definitely know you’re doing science if can you can falsify your experiment but some things fall outside this possibility such as the theory of evolution where the event has already happened and you cannot replicate it in the laboratory.

William Whewell, a British philosopher from the mid 19th century, who originally coined the term scientist (originally referred to as a natural philosopher) then coined the term consilience. Consilience means the convergence of evidence. It’s the principle that, if evidence from multiple independent, unrelated sources are in agreement, you can draw very strong conclusions even if the individual sources of evidence are not strong on their own. This is the case for the theory of evolution as independent data sets from various field such as genetics, chemistry and physics back one another up, agreeing with the mutability of species over time. Hence induction is consistent and evolution is thought of as a strong idea. Today, McInerney uses this idea in determining the origin of Eukaryotic cells, finding strong supporting evidence for a single hybridization event resulting in a single domain of life, as opposed to the three domain hypothesis.

Hence science is indeed founded by philosophers and we are the modern day “natural philosophers”. Science was originally constrained by religion, e.g. Charles Darwin’s struggle in the publication of the theory of evolution, due to the non-religious inference that humans are indeed animals. Thanks to philosophers such as Popper and Whewell we can disregard non-science and hence have come a long way since the idea of “the ladder of life” with God and angels positioned at the top rungs, then royalty, humans below, and finally animals. However we don’t often think about the philosophy of science and evolution. When I told my elder cousin that I was interested in evolutionary biology her response was “Evolution…sure isn’t that figured out?”. Before, we were restrained from addressing philosophical questions by religion, now it seems we have become absorbed in the facts and statistical data with a disregard for the broader questions that science and philosophers set forward to address. Nowadays, if you don’t adhere to popular scientific dogma, your theories easily face rejection. The majority of scientists are evaluators of data and not pioneers, creating original ideas. However, only those with a talent for original thought can be pioneers such as James McInerney who combats the commonly held belief of the three domains of life. Science is the tool to answer philosophical questions and we cannot ignore our ancestors, the philosophers, who gave birth to us scientists.

As Einstein said, in response to a physics lecturer’s proposal to introduce as much as possible of the philosophy of science into the modern physics course, “independence created by philosophical insight is, in my opinion, the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth.” (Einstein, Dec 1944)

Let us not seek only money and acceptance, let us become the seekers of truth.

Author: Maura Judge

Image Source: Wikicommons