I’ve been touring international natural history museums as part of my PhD research. The “behind the scenes” aspect of each museum is fairly unchanging; row upon row of cabinets with some very unusual objects lurking within – the taxidermic tastes of some people just leave you wondering… Aside from the obvious dissimilarities in size, the major difference between the museums I’ve visited is in the style of their public exhibits. Like any other industry, museum exhibition styles are subject to fashion trends which reflect society’s interests and inclinations at the time of the exhibit’s creation. Visiting collections in Dublin, London, Washington DC, New York and Harvard University is an interesting trip through the evolution of natural history museums.

A visit to Dublin’s Natural History Museum should be treated as an historical trip back to the golden age of Victorian interests in the natural world. The museum’s first floor gallery is typical of the “classical” approach to natural history collections; collect and stuff as many animals as possible and cram them together in display cases to be admired. Scientific information is often limited to just species names and any niggling doubts about taxidermic accuracy should be ignored (have a look at the Orang-utan’s less than life-like features on your next visit). I love this old style, not only because you never know what odd creatures are lurking around the corner but also for its testimony to the collecting frenzies of 19th century naturalists.

A quick tour around London’s natural history museum gives a flavour of the evolution of exhibition styles; from display cabinets similar to Dublin’s “dead zoo” approach through to the ultra-modern and interactive Darwin Centre where you can watch a real-life scientist at work behind a glass screen (maybe not so far removed from a zoo after all?) The human biology exhibits lie somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. The interactive displays that allow you to re-live your time in the womb and explore how your senses work represent some of the earliest changes in exhibition planning; the move from passive presentation of natural objects to interactive attempts to inform and entertain museum visitors. These changing attitudes are documented in Richard Fortey’s excellent book about life at London’s museum.

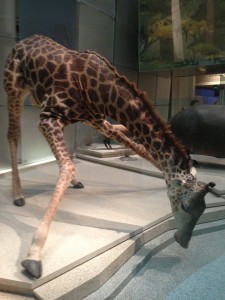

In different ways, the American museums I visited also mix old and new approaches to museum exhibits. The Smithsonian Institute seems to have a taste for dynamic and life-like taxidermy. They have a giraffe drinking from a waterhole, a leopard hanging out with its kill in a tree and lions in the middle of taking down a water buffalo.

They’re the same species as can be found in Dublin or London but their action-style poses certainly adds a bit more realism to the exhibits. You just have to wonder about what weird contortions and odd framing apparatus must have been used to preserve these animals in mid-action poses for ever more.

They’re the same species as can be found in Dublin or London but their action-style poses certainly adds a bit more realism to the exhibits. You just have to wonder about what weird contortions and odd framing apparatus must have been used to preserve these animals in mid-action poses for ever more.

The American Museum of Natural History has a different approach to adding a touch of life to their dead zoo. Many of their species are displayed in dioramas; recessed windows frame scenes from Savannah, tropical rainforest, desert and woodland life. The AMNH also has a cleverly designed and beautifully displayed wing where visitors can walk the vertebrate tree of life. Feeling somewhat Dorothy-esque, you follow the vertebrate phylogeny laid out on the ground, stopping en-route to see fossil or skeletal examples from all the major lineages. Instead of going down the “pull a lever/ push a button/ touch a screen” route of exhibition interactivity, the AMNH has enlivened the traditional natural history style by displaying their species in an evolutionary or ecological context which is far more interesting and informative for the visitor. They are certainly lovely scenes to admire, though I do admit that I spent most of my time wondering what happens when everything comes to life at night…

Although smaller in size, Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology combines all the exhibition styles of its big city museum counterparts. There are dead zoo-style cases of stuffed animals, ecological dioramas of species found in New England forests and high tech, interactive touch screens to explore the tree of life (a lovely tool but not completely up to date – because I’m pedantic I had to check how they classified tenrecs…) The added benefit of the MCZ is their inclusion of exhibits based on current and previous research of the museum and affiliated staff. They have specialised, themed exhibits based on their research expertise, I particularly loved the displays about the evolution of animal colouration and camouflage based on research from the Losos lab. Despite its limited size, the MCZ combines all major aspects of the evolution of museum exhibits; from static stuffed animals through to interactive attempts to inform visitors and clear links with active, current scientific research.

There’s clearly a huge variety in natural history museum exhibits and it’s interesting to see how each institution tackles the task of preserving their tradition while still continuing to keep a pace with the demand for new and more exciting exhibits. Our own TCD Zoology museum is no exception to this evolving museum trend as we prepare to welcome our first public visitors of the summer in just a few weeks’ time. I look forward to sharing some our own quirky museum stories; just how did our elephant, Prince Tom, fit in through the door?

Author

Sive Finlay: sfinlay[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit

Sive Finlay