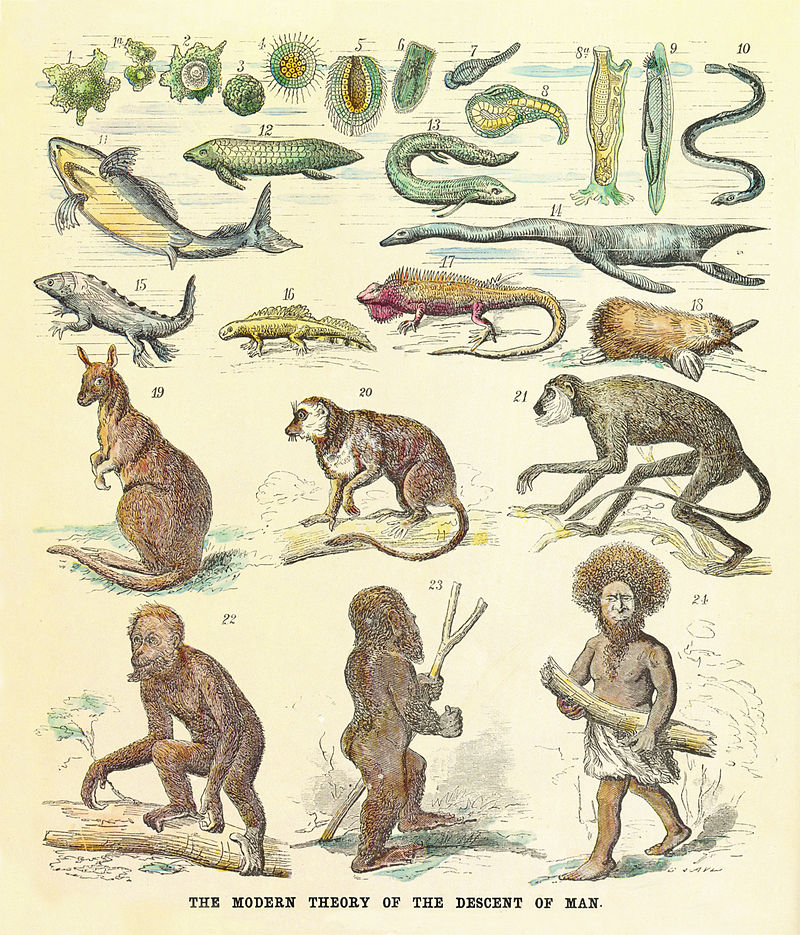

We are living in a biodiversity crisis, with many species shrinking in numbers and at risk of going extinct. To put a stop to, or at least slow down this seemingly inevitable fall into the abyss for many of the world’s species, one action that is considered effective is establishing protected areas.

“A protected area is a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.” IUCN Definition, 2008

When we imagine a protected area, we typically picture a pristine natural environment with gorgeous landscapes, thriving diversity of wildlife, and no human beings. The reality, however, is strikingly different, especially in Europe where very few locations have never been used by humans. In fact, most protected areas are under pressure from human activities.

The pressure comes in different forms: from farming to roads, from urbanization to hunting, from mining to logging etc.. We may expect that some of those threats are more harmful than others. We may also expect that some of those threats are more “central” than others. In other words, that some threats may be sources of other types of pressures. A classic example is roads, which favour the spread of invasive species and increase hunting. New roads make it easier for hunters to access more land to hunt on. If we want to reduce hunting, we could well reduce access to areas that host endangered species.

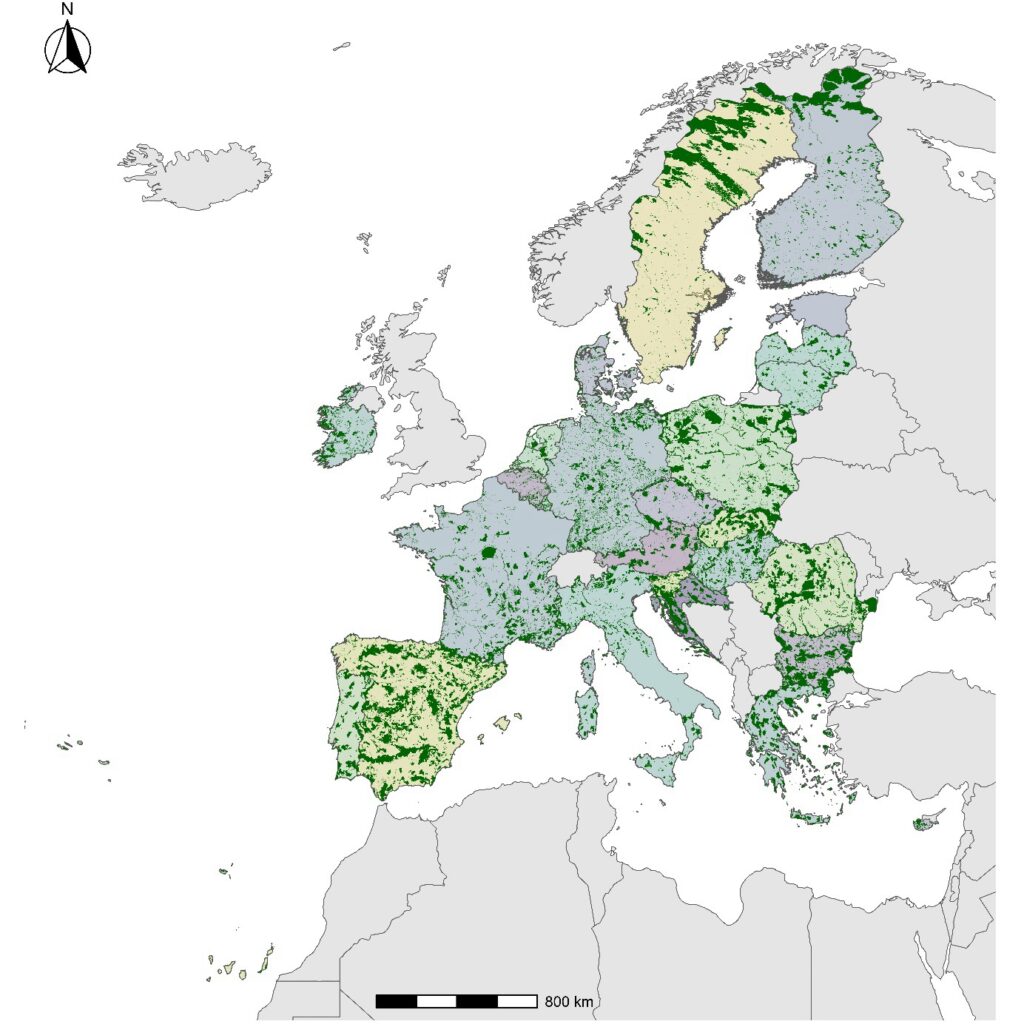

In the European Union (EU), protected areas are managed through an integrated network called Nature 2000, which includes over 27,000 land and marine protected areas and covers over 1.1 million square kilometres, an area almost four times the size of Italy. The EU collects an impressive amount of information about its protected areas. For example, data on protected species, habitats, what management actions are carried out, and importantly human activities. Remarkably, all this data is made openly available (it can be downloaded here)!

We used this data and we tried to identify relationships between human threats, hoping to provide guidance for a better management of these sites.

By analysing the data from the EU, we found that many of the human threats recorded within the Natura 2000 network are related with each other. For example, as introduced earlier, we observed that the presence of ’roads, paths and railroads’ is strongly related with ’hunting and collection of wild animals’. We also observed that ’Urbanised areas, human habitation’ is related threats such as ’Fire and fire suppression’, ’Introduced genetic material, GMO’, and ’Taking/removal of terrestrial plants’, among others. In these examples, roads and urban areas are likely acting as sources of the other types of threats. Generally, we found that threats related to agriculture and urbanization are more frequently related with other threats. In practical terms, it means that if we are going to eliminate, or at least reduce the presence, of those types of human activities we will be more likely to also reduce other threats that are associated to them. We can kill two birds with one stone, but now the birds are nasty human activities that harm ecosystems and biodiversity. Minimizing threats that are strongly related with others should be prioritized.

The full article “Examining the co-occurrences of human threats within terrestrial protected areas“, published in Ambio, can be accessed here.