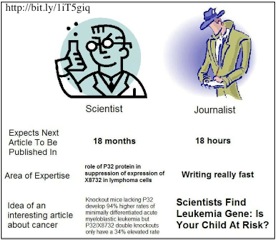

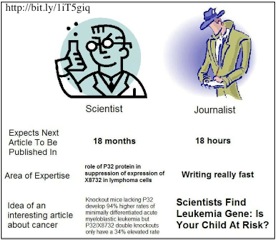

In a previous post I outlined some potential areas of conflict between scientists and the journalists who are reporting on research. Here I want to continue my look at this relationship. First off let’s start by looking at some surprising results from the social science literature which show that more often than not scientific findings are accurately reported.

In a previous post I outlined some potential areas of conflict between scientists and the journalists who are reporting on research. Here I want to continue my look at this relationship. First off let’s start by looking at some surprising results from the social science literature which show that more often than not scientific findings are accurately reported.

One study by Peters et al. (2008) reported, “interactions between scientists and journalists are more frequent and smooth than previously thought.” Another study, this time of science coverage in the Italian press, found that “There is almost invariable agreement between the author of the article and the sources” (Bucchi and Mazzolini 2003). The authors of the latter paper go on to state that, “This predominantly positive tone of science coverage, documented also by other studies of the daily press, is again in contrast with many critical stereotypes and contributions.”

There is a paradox apparent in all of this. How is it that the majority of scientists are happy with the journalistic interpretation of their studies and yet journalists are portrayed as constantly reporting the science inaccurately? Celeste Condit (2004) reports that “It was all too natural for critics [of the media] to notice and reprint examples of egregious reporting, portraying these as typical of the rapidly burgeoning area of genetics reporting.”

We should be aware that the general claim from scientists that journalists simplify scientific data could be levelled at scientists themselves. The final Nature paper tells a story without mention of any bumps on the road. Peter Medawar recognised as much when he asked “is the scientific paper a fraud?” Of course every scientific paper cuts out the difficulties encountered and smooths the rough edges.

This seems to be the answer to the question of conflict; a select few examples of sloppy journalism are used to criticise science journalism as a whole. It appears to be the case that many of the criticisms of science journalists are unwarranted.

But is this relationship something we should want? I would argue that it may not be entirely beneficial. Of course it is important that scientific work isn’t misrepresented and that there are many findings of science that ought to be celebrated but a critical article on some body of research may often be justified. As Phillip Ball says, “Making scientists happy is not the aim of science journalism…” Murcott (2009) believes science journalists’ dependence on sources makes them different to other journalists. “You could say that this is not exactly a description of a journalist — more that of a priest, taking information from a source of authority and communicating it to the congregation.” I would agree with this point and his conclusions that “The ‘priesthood’ model of science journalism needs to be toppled.”

Of course there are problems if this model is to change because as he points out “The time pressures on journalists today do not bode well for calls for more depth, context and criticism” (Murcott 2009). Colin Macilwain (2010) echoes these views and says “Scientists and the media are trapped in a cosy relationship that benefits neither. They should challenge each other more.” Naturally, researchers do not want “to be held to account by the press.” Macilwain advocates more dedicated journalistic coverage that criticises science in a way that other journalistic beats do. “Reporters and editors could then engage with sets of findings and associated issues of real societal importance in the news pages, asking the hard questions about money, influence and human frailty that much of today’s science journalism sadly ignores”.

One trend that is likely to increase conflict is the decline in the number of specialised science reporters. PZ Myers, a scientist and active blogger says “the problem with science journalism…is that too often newspapers think you don’t need a science journalist to write it. Any ol’ hack will do.” (Myers 2010). I would contend that as newspapers assign non-specialist reporters to their science beat the number of instances of bias, misrepresentation, inaccuracies etc. will rise.

It should be noted that scientists have a role to play in this too. If specialised science reporters disappear scientists will have to recognise this and be sympathetic if and when they deal with a journalist who is relatively ignorant of the science. In this way there will be less room for inaccuracy and misrepresentation. I would agree with the conclusions of a piece in the journal Nature that scientists by working with journalists can “ensure that journalism programmes include some grounding in what science is, and how the process of experiment, review and publication actually works” (Nature 2009).

The current relationship that science journalists have with their sources means that, although there is room for conflict, it is far from inevitable. Indeed, it seems that Colin Macilwain’s concept of a “cosy relationship” is a more accurate representation. In conclusion I would suggest that there are two forms of conflict that can occur between science journalists and their sources. There is the ‘watchdog approach’ whereby journalists are skeptical of their sources, investigate their motives and question their research. This, I would argue, is something that society should have even if it generates some friction between journalist and source. The second area of conflict is that which occurs when journalists misrepresent, misquote and inaccurately report the science. This, of course, is not something anyone wants.

Author: Adam Kane, kanead[at]tcd.ie

Photo credit: http://gloucesterconcordes.ca/welcome/extra-extra-read-all-about-it/

References

Anderson, A Peterson, A David, M. (2005). Communication or spin? Source-media relations in science journalism. In, Allan, S Journalism, critical issues. England, Open University Press. p. 188-198.

Ball, P. (2008). When reporters attack. Nature. 321, p.204-205.

Bubela, T Caulfield, T. (2004). Do the print media “hype” genetic research? A comparison of newspaper stories and peer-reviewed research papers. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (9), p. 1399-1407.

Bucchi, M. Mazzolini, R. G. (2003). Big science, little news, science coverage in the Italian daily press, 1946–1997. Public Understanding of Science. 12. p. 7-24.

Condit, C. (2004). Science reporting to the public, Does the message get twisted? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (9), p. 1415-1416.

Conrad, P. (1999). Uses of expertise, sources, quotes, and voice in the reporting of genetics in the news. Public Understanding of Science. 8, 285-302.

Dickson, D. (2005). The case for a ‘deficit model’ of science communication. Available, http,//www.scidev.net/en/editorials/the-case-for-a-deficit-model-of-science-communic.html.

Goldacre, B. (2005). Don’t dumb me down. Available, http,//www.guardian.co.uk/science/2005/sep/08/badscience.research.

Hansen, A. (1994). Journalistic practices and science reporting in the British press. Public Understanding of Science. 3, 111-134.

Ipsos MORI. (2009). Doctors Remain Most Trusted Profession. Available, http,//www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2478.

Macilwain, C. (2010). Calling science to account. Nature. 463, p. 875.

Medawar, P. (1964). ‘Is the scientific paper a fraud?’ Available, http,//contanatura-hemeroteca.weblog.com.pt/arquivo/medawar_paper_fraud.pdf.

Murcott, T. (2009). Science journalism, Toppling the priesthood. Nature. 459 (7250), p. 1054-1055.

Myers, P.Z. (2010). The problem with science journalism…. Available, http,//scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2010/03/the_problem_with_science_journ.php.

Nature. (2009). Cheerleader or watchdog? Nature. 459 (7250), p. 1033.

Nelkin, D. (1996) Medicine and the media, An uneasy relationship, the tensions between medicine and the media. The Lancet. 347 (9015). p. 1-10.

Peters, H.,P. Brossard, D. de Cheveigné, S. Dunwoody, S. Kallfass ,M. Miller, S. Tsuchida, S. (2008). Interactions with the Mass Media. Science. 321 (5886), p.204-205.