Last December I was asked to participate in the TEDxUCD 2015 event. The event included 9 national and international speakers with a wide range of ideas worth spreading. Despite being asked to participate only two days prior to the event luckily I could draw on the wide research area encompassed in my new Post Doc position using the COMPADRE and COMADRE databases to study patterns in demography and life-history evolution in plant and animals. As I couldn’t possible fit all the ideas worth sharing from the fields of demography and life-history evolution into an eleven-minute entertainment talk I focused on research related to the variation of maximum lifespan across vertebrates. In particular, I discussed research originating from my PhD on trying to understand why some species seem to live far longer than we would normally expect and how their ecology may be related to this (http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/281/1784/20140298).

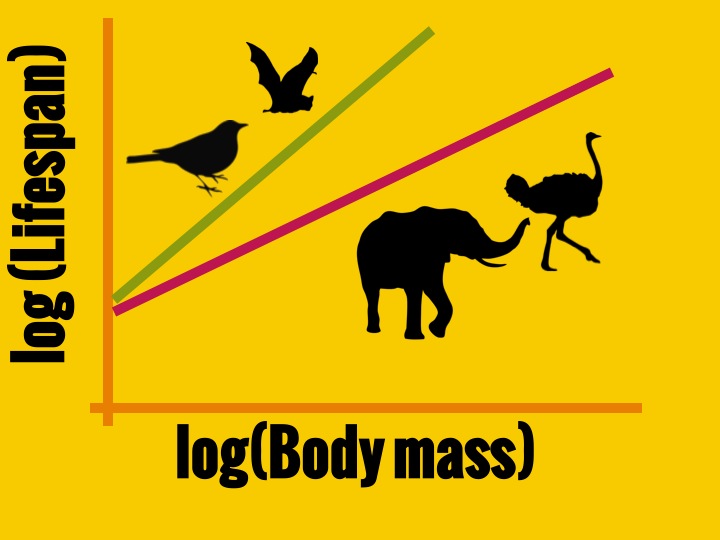

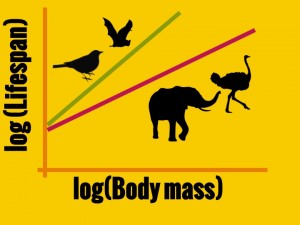

My approach is that it is the species that are found at the extremes of nature that can often be the most informative. Whales tell us about the limits of size, cheetahs the limits of speed and ants the power of cooperative behavior. However, it is not always the Guinness book of record style species that are the most interesting, for when it comes to understanding aging it is oddball creatures such as the bats and the naked mole rat that are the unsightly stars of many aging studies. The reason for this interest is because these animals seem to have the inside scoop on the elixir of youth with both bats (>40 years max) and naked mole rats (>30 years max) living an order of magnitude longer than expected for their size.

Despite this we still have little idea of not just how, but why these species have such life-history strategies. This is important not simple with regards to understanding life-history evolution, but because researchers are beginning to target species and genes with potential links to the abilities that keep aging at bay. For example, the extreme lifespan of naked mole rats has been touted as being the result of the reduced danger associated with its subterranean lifestyle. This has led researches to target species and genes associated with with living underground, such as genes related to their stretchy skin, as these are to thought to be themselves linked with reducing sources of age related mortality such as cancers. However, the role of subterranean living in increasing lifespan is still debated, leaving such a targeted approach in danger of missing the mark in other scenarios.

My idea worth sharing is that we should not just find these unusual species but also understand what evolutionary and ecological drivers shaped these species. With the help of more detailed datasets like COMADRE and COMPADRE we can begin to understand the evolutionary and ecological drivers that lead to species at the extremes of life history evolution. We should aim to not just know who the oddball stars of life-history studies should be, but why they really are stars.

Author: Kevin Healy

Contact: @healyke