The concept of using bacteria and other microbes to test some of the big questions is creeping more and more into the world of ecology and evolution. Evolutionary biologists have been coming around to this idea for many years now (see Lenski’s experiment for a wonderful example of this) but the concept is still hard for most ecologists, particularly empirical ones to swallow. This is primarily a function of the microbial systems being thought of as ‘too simplistic’ and ‘unrealistic’ to apply to real world populations. In a review in 2009 Angus Buckling and colleagues very elegantly address the above charges and some of the other most frequently raised arguments against using bacterial microcosms. My argument (and his!) essentially comes down to two things:

1. Ecologists are supposed to be devising models and experiments to understand the dynamics of real world populations and the consequences of anthropogenic impacts on the organisms that inhabit the planet and yet they are largely ignoring the biggest Kingdom of organisms-Bacteria!

2. While nobody is suggesting that what happens in a 200ml microcosm tube will perfectly mimic or predict the exact response of a 200acre coral reef, why can they not be used as models to help test some of the theories or predictions that might equally affect larger systems?

Microbial systems have very similar dynamics to most other empirical food webs, in particular aquatic ones with highly size-structured predator-prey interactions, social cooperation and complex community networks. The importance of bacteria and microbes in the environment and their role in disease is undeniable and widely recognised meaning that individually bacteria are some of the most well studied organisms out their in terms of their genetic information and growth patterns. This can be used to the advantage of ecologists and evolutionary biologists by isolating strains of particular interest and culturing them very easily in laboratory conditions over short time periods to yield potentially very powerful results when viewed at the population or community scale.

One of the big problems in the field of ecology is linking empirical and theoretical study results; they frequently disagree due to the time scales, interactions and networks involved. The problem is basically that, however good the theoretical model, it cannot encompass all of the complexities of a natural system, and, similarly, while the empirical studies are more difficult to rebuke for their lack of realism or complexity, it is often impossible to disentangle the many different interactions taking place to get to the root of the question. What is therefore needed is a means to bridge this gap and provide logistically feasible model systems for testing more generalized ecological and evolutionary theory. I think the microbial systems might be a partial solution to this problem, as well as being fascinating for their own sake they can really aid in the developing and testing the drivers and disentangling the complex interactions in ecological and evolutionary processes. What they lack in size they certainly make up for in potential!

Author

Deirdre McClean: mccleadm[at]tcd.ie

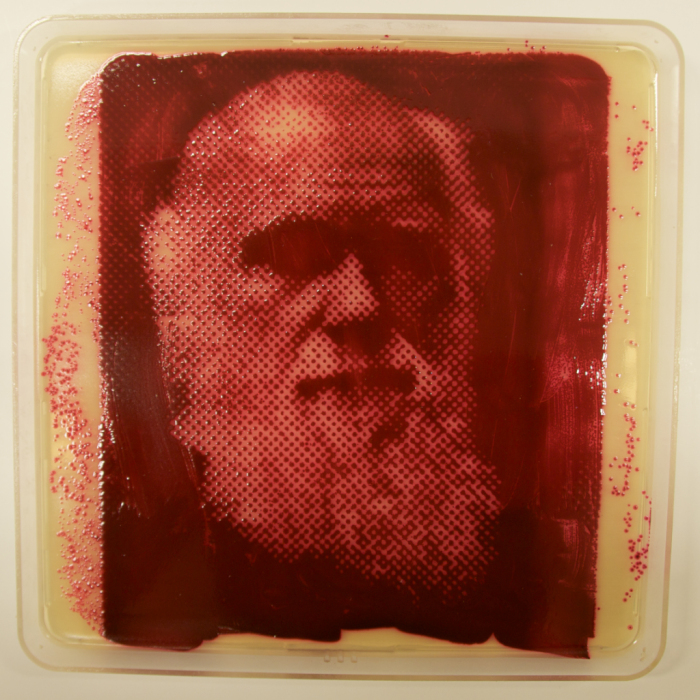

Photo credit

Zachary Copfer: http://sciencetothepowerofart.com/