Thanks to the magical (and sometimes frustrating!) technological capabilities of Google+, every fortnight we have international phylo/macro journal club meetings which span three continents and even include elements of time travel (the Australian participants are always in the future!). Among the varied topics we cover, one of our recent sessions was a discussion of Samir Okasha’s book, Evolution and Levels of Selection. Evolutionary biology is an empirical science which also receives attention from philosophers. The two approaches are often difficult to reconcile so Okasha’s book is a welcome bridge for the gap between philosophical theory and practical biology. We mainly focused on the chapter which deals with species selection, clade selection and macroevolution and addresses the units of selection debate.

As a brief background, the debate hinges on the unit(s) and level(s) at which evolution by natural selection operates. Biological structures are inherently hierarchical. As researchers we tend to focus on specific organisational levels, so community ecologists will have very different concerns and interests to cell biochemists. Biological structures are shaped by evolution but the question is at which level(s) in the biological hierarchy does natural selection act? The theory of natural selection is an abstract concept; as Lewontin describes, the tripartite conditions for evolution to occur are phenotypic variation, differential fitness and heritability. So which level of biological organisation satisfies these requirements? Well it seems like it depends on who you read and who influenced your evolution teachers!

In the UK and Ireland we are generally taught evolution from a gene-centric point of view – the Dawkins school of thinking in which selection acts at the level of the individual and the unit of selection is the gene, and only the gene. However, across the pond, there seem to be more proponents and acceptors of higher or multi-level selection theory; the idea (following Stanley, Gould and Eldredge among others) that natural selection is not restricted to genes as the sole units of selection. It’s a confusing debate, especially when it comes to teasing apart the concepts of levels and units of selection; Okasha argues that a gene’s-eye view (genes as the units) can still be adopted for selection acting at various hierarchical levels. Furthermore, concepts of species level selection tend to become confused with group selection – a notoriously controversial concept which is guaranteed to set alarm bells ringing for many people.

Returning to Lewontin’s criteria, the basic idea of species level selection is simple. If species vary in some sort of traits and that variation gives rise to differential extinction or speciation rates, then some types of species will become more common than others. This approach is particularly common from palaeontological or macroevolutionary perspectives. If you’re interested in long-term evolutionary trends such as patterns of differential lineage abundances or extinction and speciation trends, it’s intuitive to treat the species as the level at which selection acts. This highlights a fundamental component of this debate: the gene-only-level of selection is usually advocated by microevolutionists; those who are interested in changes at the genetic level. In contrast, multilevel selection theory receives support from macroevolutionists who, due to their fundamentally different approaches, consider individual species to be their smallest units of interest.

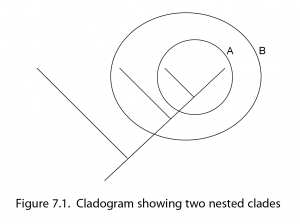

When you think about species selection it is often easy to confound it with clade selection yet Okasha draws a clear distinction between the two concepts. Clades are, by definition, monophyletic; comprised of a single ancestral species and all of its descendant species. Unlike species, clades cannot split to create new clades with ancestor-descendant relationships because any new clade will inevitably be nested within the old clade (the diagram in Okasha’s book makes all of this far clearer than my description!)

Speciation and extinction rates are clearly not uniform; some lineages radiate into many different types of species which enjoy happy evolutionary lives (think of our arthropod-dominated world) while other evolutionary lineages produce fewer species. The question is whether these patterns are the result of species-level, macroevolutionary processes or whether emergent, species-level properties can be explained from selection acting at the genetic level. As an “acid test” for genuine species selection, Okasha proposes Elizabeth Vrba’s view that species selection must in principle (though not necessarily in practice) “be able to oppose selection at lower hierarchical levels”. Otherwise species level selection merely describes processes which can also be explained from a genetic-selection stance. For example, species selection may have been involved in the evolution or maintenance of sexual reproduction; the advantages of sexuality at the species level may have outweighed the two-fold cost of sex at the individual level and therefore favour the evolution of sexual over asexual lineages.

However, there seems to be a general paucity of clear examples which conform to Vrba’s acid test. One intriguing suggestion as to why this may be the case is time. The generation times of species producing new lineages are clearly far longer than the generation times of individuals’ reproduction so perhaps comparatively sluggish species selection processes have not had sufficient time to oppose evolutionary patterns which arise from individual selection?

Confused? It’s an interesting debate but certainly not one for the faint hearted and the fact that each philosopher/scientist/punter on the street seems to have jargon and slightly differing definitions of their own only serves to cloud the murky waters further. It is, however, interesting to contemplate how our own research backgrounds and the inclinations of our teachers influence our approach to the debate. If you’re interested in these kinds of questions then Okasha’s book is well worth the read or else you could join in with our Phylo/Macro journal club meeting; wherever you are in the world we’re on a Google+ hang out near you!

Authors: Thomas Guillerme (guillert[at]tcd.ie, @TGuillerme) and Sive Finlay (sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay)

Image Source: Okasha 2006, Evolution and the Levels of Selection