“Green future”, “Green initiatives”, “Green energy”

All references to the color green are impossible to avoid if we want to preserve or improve the environment. It is clear that “going green” is in, but which shade of green should we look at? There is the ‘bright electric green’, commonly posed on renewable energy advertisements and infographics. There is also the ‘deep forest green’ often pledged in biodiversity conservation campaigns. However, the question is, can we generate an environmental plan that actually delivers an appealing blend of both ‘electric’ and ‘deep forest’ green?

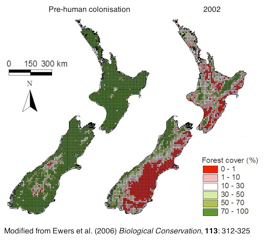

In our recent work, we set out to determine what the optimal shade of green for Ireland’s future is. Like many countries, Ireland recognizes the need to urgently transition to a low-carbon economy to avoid the devastating impacts of unimpeded climate change. To meet our decarbonisation goals, Ireland has developed a Climate Action Plan 1. The goal of the Climate Action Plan is to achieve a net zero carbon energy system for Irish society by 2050. Specific actions include increasing the amount of electricity generated from renewable sources from 30% to 80% by 2030, establishing 8,000 hectares of newly planted trees per year, and funding the restoration and rehabilitation of peatlands. So it seems that the solution is quite straightforward – convert all current land uses to renewable energy infrastructure, new forests, and peatlands. Problem solved?!

Not so fast… In addition to the climate crisis, we are also facing an equally urgent biodiversity crisis. These two green problems can’t be solved independently. The biodiversity and climate crises are entwined in a complex system of feedbacks, with biodiversity part of the Earth system regulating climate, and climate in turn determining biodiversity patterns and trajectories. Ireland is a trailblazer in acknowledging that a synergistic solution is needed, and in May 2019, became the 2nd country worldwide to declare a climate and biodiversity emergency (Dáil Éireann, 2019). However, recognizing that climate and biodiversity require a coordinated response is only a first step. Implementation is going to be far more complicated. We need a plan, and we need it fast.

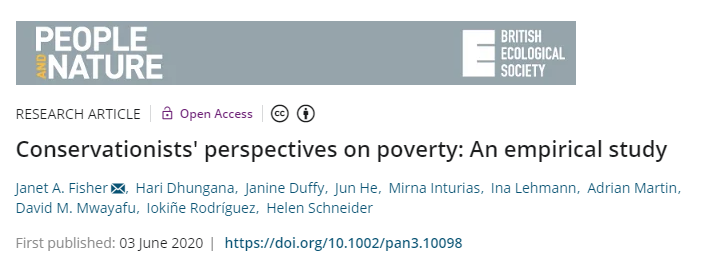

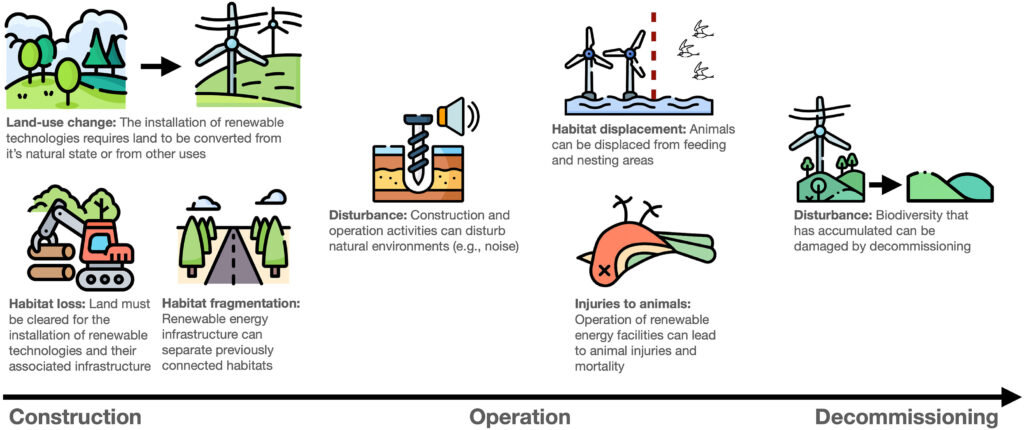

To come up with the plan that would be the best for both climate and biodiversity, we went through the major goals of the Climate Action Plan and reviewed the scientific literature to determine how to meet those objectives in the most biodiversity friendly way possible. We identified the major threats that climate actions, such as increased renewable energy infrastructure, could impose on biodiversity (Figure 1) 2.

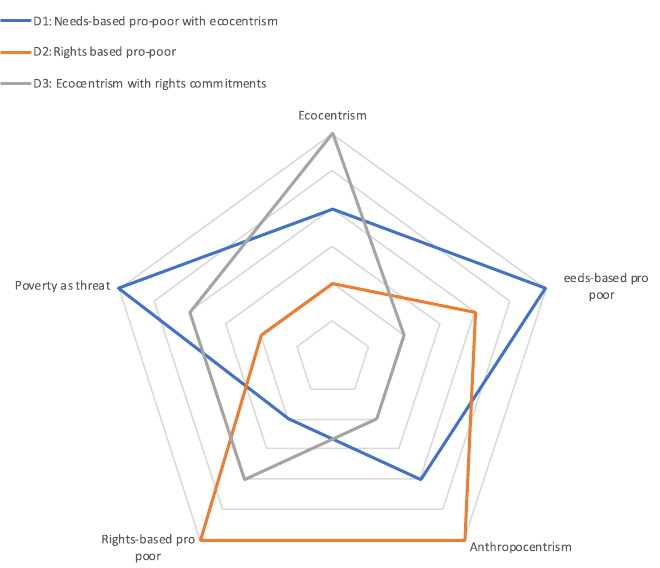

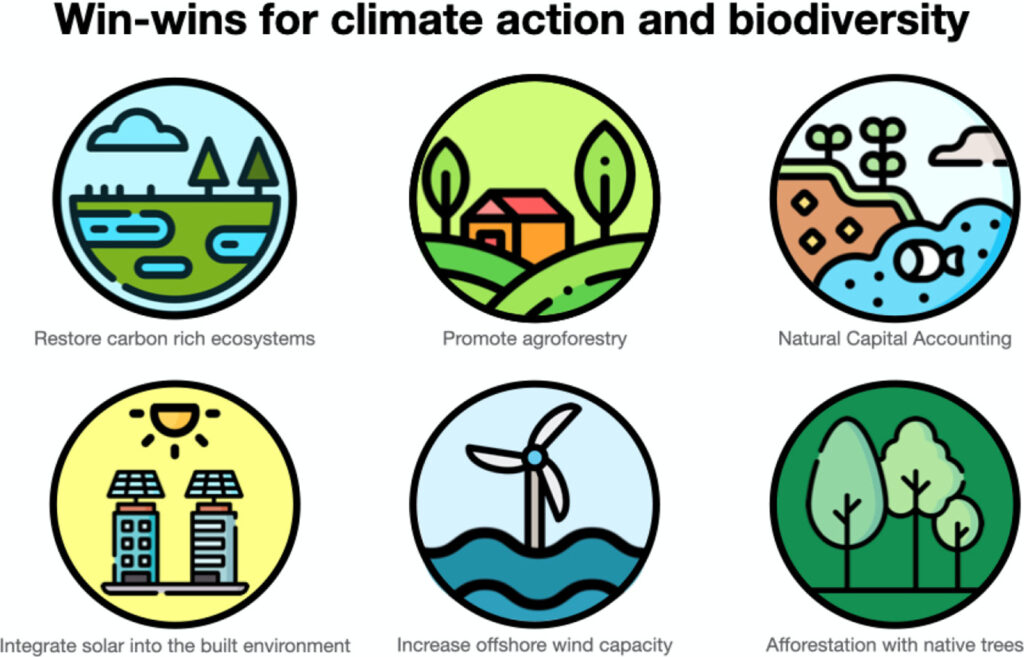

Along the way, we also found that many of the proposed climate actions can be implemented in ways that don’t harm biodiversity, but actually promote biodiversity: our “win-wins”. For Ireland, these include increasing offshore wind capacity, rehabilitating natural areas surrounding onshore wind turbines and limiting the development of solar photovoltaics to where humans have already erected structures, the so-called “built” environment (Figure 2).

Ultimately, biodiversity-friendly renewable energy can be achieved by prioritizing renewables that are the least damaging and ensuring that infrastructure development is carried out as sensitively as possible in order to protect, restore, and enhance biodiversity. This could look different depending on where in the environment we are talking about, which is why choosing an appropriate site for each method is critical – we need a plan!

We hope that this work can form the basis for that plan for Ireland and stimulate broader discussions on what this looks like for other countries. By synergistically mitigating both our climate and biodiversity crises, we can ensure that Ireland’s future is Emerald Green.

About the author: Courtney Gorman is a postdoctoral researcher and project manager for the Nature+Energy project at Trinity College Dublin. She has a PhD in Biology from the University of Konstanz in Germany.

References:

1. Government of Ireland. Climate Action Plan. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/ccb2e0-the-climate-action-plan-2019/ (2021).

2. Gorman, C. E. et al. Reconciling climate action with the need for biodiversity protection, restoration and rehabilitation. Science of The Total Environment 857, 159316 (2023).

Blog amended from first publication on Campus Buzz.