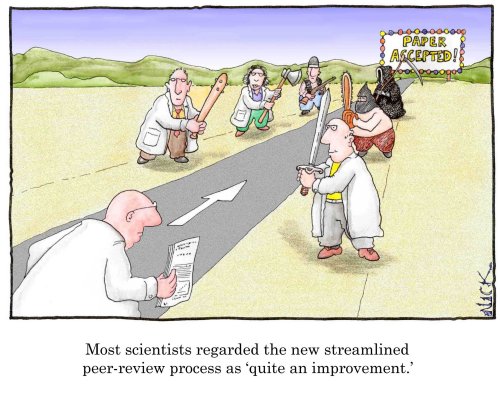

We rolled out of bed on January 6th, 2014, with the somewhat comforting- but mostly jarring, give-me-a-cup-of-coffee-immediately-inducing- knowledge that the holiday season was over and it was time to get back to our normal schedules. And that happily means everyone once again gathers for Nerd Club before lunch on Tuesdays. Aided by left over boxes of Roses, the first Nerd Club meeting of 2014 kicked off with a transferrable skills session discussing the submission of papers and how to cope with the peer review process. Many of the PhD students in the group (myself included) are working towards our first, first author paper. It can be a long and discouraging process, so we were eager for advice from our more experienced members.

We wanted to cover four topics; (1) issues of authorship, (2), choosing a journal, (3) choosing and responding to reviewers, and (4) dealing with rejection (sniff!). I’m going to summarize our discussion on the first two points, which we talk about during week one of this two-week session.

Issues of authorship

- Who should be included; criteria for authorship

We came up with several ways to determine exactly who should be included as an author on a scientific publication. A popular method is asking, “could this paper have been completed without his/her contribution?” A common issue with this method is considering technical support. A research assistant or undergrad for example may spend hours helping with an experiment; perhaps without them you wouldn’t have completed the work. If there was no intellectual contribution however, some argued there may be grounds for excluding such a person as an author. A similar question one can ask is, “has the paper been made materially better by the person?” Again, you run into the same problem; what about editors, and how much exactly does someone need to contribute to qualify? One extreme view is that you should refuse authorship on a paper unless you feel you could give a talk about it. While this is a great goal to aspire too, there was some controversy in the room on the feasibility; what if you did a substantial amount of modeling for a paper and without your contribution it would not have been published, but the paper was on an area in which you have little expertise? You may understand your contribution completely, but that doesn’t mean you’re ready to discuss Type I diabetes or the complexities of insect flight. In general the group agreed that you should at least be able to discuss the main goals and conclusions of the paper, even if you wouldn’t present it at a conference. More and more journals (Proceedings B, Science, etc.) are requiring a section listing each author’s contribution, so it’s a good idea to make these decisions early as you will be held accountable for them when you submit.

Another piece of advice that seems to fall under the “who” category is how to decide on the author affiliations listed on the publication. Usually the affiliations from where the person did the work are the ones that should be included, even if the person has moved on to another job or institution. It is possible, however, to add a current address so that authors can still be contacted by readers.

Two final piece of advice: first of all, if you’re the first author on a paper, it is probably your responsibility to start this discussion and to make final decisions on who will be included (of course for PhD students it’s going to be necessary to consult your supervisors). Second, if your name is listed as an author you should at some stage read the entire paper in detail and make helpful comments, not only to improve the quality, but also to ensure you understand the work and conclusions completely.

- What are the most important names on the list?

I think most of us were aware that there are two important places in that sometimes-long list of authors, first and last. First author is the person driving the work, who usually claims the most ownership. The first author will get the most recognition for the paper among the scientific community as well. Some journals allow co-first authors, however someone’s name will have to be placed first on the list. When I read a paper, if there are more than two authors I almost always remember only the first, and I’m not alone.

The last author is considered the senior author, the person who likely received the funding to do the work and who probably leads the lab or research group the first author is working in. Surprisingly to some of us, it is possible in some journals to have co-senior authors as well.

Finally, the corresponding author is the person who will physically submit the paper and is responsible for responding to reviewer’s comments. They are also the one to contact if someone has a question about the work. Overall we decided that corresponding author singles one of the people on the list out, but it doesn’t really distinguish them in any other way.

- When to discuss it and make changes?

The consensus from our group was that yes, issues of authorship can sometimes be awkward and complicated, but it is important to have conversations about it early and often with your collaborators. Otherwise a slightly uncomfortable situation can turn downright ugly, and can cause rifts between research groups and partners. So, to avoid discomfort, talk about authorship as soon as possible and throughout the writing process.

We also discussed adding and removing people from your author list. It is usually fine to add an author at almost any stage, so long as you feel their contribution was worth authorship. Removing an author at almost any stage is usually uncomfortable. Because of this, if you’re in a situation where you feel you did not contribute enough to a paper to be an author, it is best practice to ask to have yourself removed. If your coauthors refuse, then at least you can publish with a guilt-free conscious. Of course if at any stage you don’t agree with what is said in a publication or you feel something unethical or unscientific was done, you have the right to insist that your name be removed. Never publish anything you don’t believe in or agree with!

- Where in the list your name appears; highlighting your research

A really useful piece of advice: if you find yourself in the middle of a long author list-but you know you’ve contributed in a significant way to a paper- don’t be afraid to star or highlight this on your CV. It’s really important to show future employers that you had a meaningful role in the process, and to highlight you skills.

Choosing a journal

After a rather lengthy discussion about authorship, we had a little time left to talk about how to choose a journal for your publications. We did come up with some helpful methods and tips. First, your paper must obviously fit the aims and scope of a journal. Second, you can choose a journal based on its readership- will your research get to the people you want or the people that will care about your work? We thought that in an age where people rarely if ever sit down with a physical journal or magazine, this isn’t always the best way to go (although perhaps you can choose by who you think will receive the table of contents in their email box!) Third, some choose by the impact factor of the journal, a perhaps less idealistic but more realistic view of the process. Yet another method is looking at where most of your citations came from, and trying to submit to that journal. And finally there are practical reasons to choose a journal such as word count or number of figures allowed.

There were two pieces of advice I found particularly helpful in this discussion. First, consider having a list of possible publications you would submit to, in the order you would attempt, before writing. It can be soul crushing to write a beautiful paper for Biology Letters, with its strict structure and word count, only to be rejected and required to completely rewrite a draft for a different journal. Perhaps you have the time to do this, but if it’s the final year of your PhD that may be a poor idea. Finally, when constructing said list, have the top 20 journals in your subject(s) printed out, and highlight the ones you tend to like to make the choices easier.

Stay tuned for the next installment of this series, where we will summarize our discussion on choosing and dealing with reviewers and dealing with rejection- a topic we’re all sure to face throughout our scientific careers.

Author: Erin Jo Tiedeken, tiedekee[at]tcd.ie, @EJTiedeken

Image Source: phdcomics