Part of our series of posts by final-year undergraduate students for their Research Comprehension module. Students write blogs inspired by guest lecturers in our Evolutionary Biology and Ecology seminar series in the School of Natural Sciences.

This week, views from Kate Purcell and Andrea Murray-Byrne on Kendra Cheruvelil’s seminar “Understanding multi-scaled relationships between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems”. (See Kendra’s blog about her trip to TCD).

The Power of Knowledge

As the old saying goes: “knowledge is power”. As scientists, a comprehensive understanding of that which we are studying is the key in enabling us to implement our research in a practical manner. From the perspective of an ecologist, compiling a large dataset can be costly – both in time and money. However the benefits of having a centralized dataset can be invaluable. Dr Kendra Spence Cheruvelil, an associate professor at the Michigan State University, has carried out extensive work on lakes in Michigan. Her work highlights the importance of compiling knowledge into shared datasets.

Cheruvelil recently gave a seminar in Trinity College on her work on Michigan lakes. Cheruvelil explained how data on the lakes in Michigan from governmental departments is not standardized. The data can therefore be used to draw incorrect inferences about the lakes in question. This example highlights the need to have a collaborative database where such information can be shared.

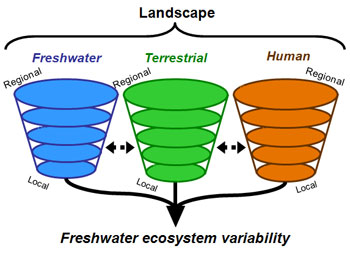

As well as explaining the need for a complete, standardized dataset, Cheruvelil demonstrated the importance of understanding the regional spatial scale when extrapolating information to make inferences about lake systems. Cheruvelil and colleagues stated the importance of fully understanding systems from the local to the continental scale. According to Cheruvelil, in order to make correct inferences we need conceptual models of relationships across scales, large datasets, and robust modeling approaches to deal with these data.

Cheruvelil and colleagues studied 2,319 US lakes in 800,000 km2. Using two variables – total phosphorus and alkalinity – they found that there was a high level of among-region variation in lakes. The found that the amount of regional variation present depends on what you look at, and as spatial extent gets bigger so too does regional variation. The amount of regional variation therefore depends on the spatial extent, the response variable of interest (with total phosphorus < alkalinity) and the regionalized framework.

Why is knowing what drives ecosystem processes in lakes important? Cheruvelil made the point that having these data allows for interactions between local and regional scale variables to be accounted for. Inferences can then be made about these variables and how they may drive ecosystem processes in other lakes with less data. The landscape features driving lakes are multi-scaled (local and regional), both hydro-geomorphic and anthropogenic, difficult to disentangle and different according to the response variable of interest.

Cheruvelil’s research is important, especially from a management point of view. It shows the importance of using both local and regional scales when making inferences about any ecological system, including lake systems. Making better and more informed inferences about the driving factors behind the lakes are especially important as we’re in an era facing large-scale climate change.

Author: Kate Purcell

———————————————————————————

Paint by numbers: using inferences as a guide to paint the bigger picture

Limnology is the study of inland waters, including lakes, rivers, streams and wetlands. Dr Kendra Cheruvelil is a landscape limnologist currently carrying out research on a huge dataset of lakes in the US. She began her talk by discussing the implications of this kind of work. Her research attempts to integrate freshwater and terrestrial landscapes. As she pointed out – the map of an area you choose to show depicts exactly what you want someone to see. She illustrated this point by showing different land use maps for the state of Michigan. Michigan looks like quite a dry place when you only include lakes on the map, but when streams and wetlands are also included the picture of the freshwater ecosystem is very different!

Cheruvelil compiled a huge multi-scaled (local and regional) and multi-themed (like geology and land use) dataset from existing databases. These databases came from different organizations and in total she ended up with data on 2319 US lakes in a 800,000km2 area. This huge dataset was necessary for her equally big questions. Firstly she asked how much among-region variation is there, and secondly she wanted to know what the likely causes of this variation (if any) were.

Because ecosystem variation is driven by things like hydrology, geomorphology, as well as anthropogenic and atmospheric factors, on different temporal scales like decadal or seasonal, and different spatial scales like local or regional, the research area can be quite messy in your head (at least it was in mine!) but Cheruvelil broke it down nicely and made it a lot more digestible.

Two variables she chose to look at were total phosphorus and alkalinity. These were chosen as they can indicate stressors: total phosphorus as it can show eutrophication, and alkalinity as it can indicate acidification. They also provide a nice contrast as total phosphorus is considered to be important on a small scale, whereas alkalinity is broader as it has to do with geological features. Using hierarchical models to test the data (which I won’t dwell on because it’s a little above my head!), Cheruvelil found that a high proportion of variation is regional, for example about 75% of the variation in alkalinity was regional. This did, however, vary depending on which regionalization framework she used, but she picked a hybrid model that encompassed both freshwater and terrestrial factors, so despite the different results depending on the framework I think she gave good reasons for picking the one she eventually used.

As far as her second question – the likely causes of this among region variation – she tested the data with conditional hierarchical models (which again I won’t go into, but neither did she which was for the better I think!). Results here suggested that a few regional variables explained a high proportion of the regional variation. However, she was careful not to jump to conclusions that these variables were driving among region variation, and she clearly explained that there are most likely some confounding variables which are hard to disentangle using her methods.

Okay, so you want to study all these lakes and see if they vary among regions – but why? Why on earth is this important? These are valid questions that you may be asking yourself – and questions Cheruvelil was prepared for. She explained how making inferences from a sample lake is important when considering the bigger picture, for example when going from a local level of an individual lake and its watershed to the regional level of grouped lakes within a similar geographical region, to finally all the way up to a continental scale. The void she is filling with her research is the regional level – building models that will allow future researchers to extrapolate from their study lake and infer things at broader scales to see the bigger picture. This is important as most studies on ecosystems will be on a single lake, and I think the take home message was that findings at the local scale may or may not apply to other lakes, depending on how similar they are and if they are in similar regions.

Author: Andrea Murray-Byrne

Image Source: Landscape limnology research group http://www.fw.msu.edu/~llrg/