Academic publishing: the currency of any research career. It’s all very straightforward; take your most recent ground-breaking results, wrap them up into a neat paper, choose the perfect journal, allow said paper to persuade an editor and reviewers of your brilliance and bask in the reflective glow of getting your research out into the world. Whether you see this rosy scenario as a target or delusional and unattainable aspirations, things rarely work out so smoothly. Instead, every researcher must learn to deal with the topic of one of our recent NERD club discussions; reviewers, rejections and responses. As a collective of staff, postdocs and postgraduate students, here are our thoughts on the dos and don’ts of dealing with the three r’s of academia.

1) Reviewers

Some journals invite authors to suggest reviewers or editors for their papers. If this happens, pick who you think is the “best” person whether that’s because the person is an expert in your field (although see our final point below), likely to give a fair review or because they are familiar with your work. Only suggest people to be reviewers if they have published themselves i.e. aim at the level of senior graduate student or from post-doc upwards. It’s also a good idea to choose someone that you’ve cited a lot in your manuscript (no harm to get on their good side). Equally, if you gave a conference talk recently, remember that person who seemed so interested in and enthusiastic about your work in the pub afterwards – chances are that they might be a fair and favourable reviewer. We also thought that, if you feel it’s necessary and you have a good reason, it might be a good idea to make an editor aware of people who you would prefer not to review your paper. However, be warned of the rumours that some editors may prefer to ignore such preferences and deliberately choose people from that “exclusion” list as reviewers.

In contrast, when selecting potential reviewers or editors, don’t choose someone who you have thanked in the acknowledgements of your manuscript. These are usually people who helped out or offered advice at some stage during the research so they would have a conflict of interest when it comes to reviewing the manuscript. Of course, you can also use this guideline to your advantage by seeking advice from and therefore acknowledging people who you definitely want to avoid as potential reviewers… Also from a conflict of interest point of view, don’t suggest your main collaborators, close friends or people from your own institution as potential reviewers. Similarly, for obvious reasons, don’t choose someone as a potential reviewer if you know that they dislike you or your work!

Once you have considered all these points, our final piece of advice about choosing reviewers or editors is don’t get hung up on it! Your preferred reviewers may not accept the manuscript, particularly if they are the senior, time-limited experts in your field. Finding reviewers for a manuscript is ultimately a lottery so, having thought about a few of our suggested guidelines, there’s no point in agonising over the process too much.

2) Rejection

It’s never pleasant to think about but your chances of rejection in all aspects of academia are high. Rejection of a manuscript can be particularly disheartening as it represents a dismissal of months if not years of your hard work. Our main piece of advice is not to do anything hasty. However unfair, pedantic or ridiculous the reasons which “justify” the rejection may initially seem, their bitter sting usually mellows if you take the time to sleep on it (after getting cross and having some comfort food/drink/other activities…). Similarly, don’t ruin your Friday evening/weekend/holiday by obsessively checking your emails for an editor’s response which will more likely than not be negative.

After hopefully returning to a somewhat more rational state, try to take the reviewer’s comments on board. The constructive ones will help you to make a better paper and parts which reviewers didn’t understand are often because you could have clarified your points better. Ultimately, it’s important to be realistic; the chances of rejection of a manuscript are high so be prepared to resubmit elsewhere (think back to our previous advice about working down the list of journals for which you feel your paper is suited). You could even have another version of the paper drafted and formatted for the next journal on your list even before you receive a response from your initial submission. It may take an initial investment in time and energy but at least the next version of the paper is then ready to go if you’re unlucky enough to receive a rejection from your first journal of choice. The most important advice to emerge from our discussion was to be thick skinned and not to take rejection personally. You can’t publish without experiencing rejection so it’s important to share your experiences (both good and bad) and to listen to the advice and woes others. You’re not alone!

Our final cautionary point was that you don’t necessarily have to accept rejection. If your paper was rejected on the basis of reviews which you think were poor, biased, unfair or just completely off the mark, it might be worth arguing your case with the editor and/or reviewers. HOWEVER, only take up this tactic in exceptional circumstances where you have a VERY strong case to back up your points. If you get a reputation for being petulant, argumentative, obstinate or just downright rude it can only serve to seriously aggravate an editor and damage your future publishing prospects if not your wider research reputation.

3) Responding to comments

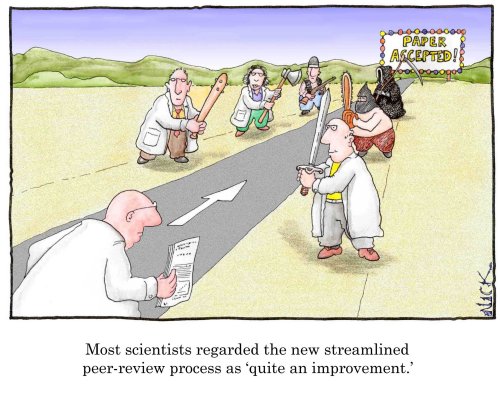

Hooray! You’ve got through the reviewing gauntlet, dodged the cold blow of outright rejection and now there are just a few reviewers’ comments standing between you and potential publication glory. We came up with lots of dos and don’ts for how to deal with reviewers’ comments.

Most importantly, be polite and positive. No one was obliged to review your work so thank the reviewers for their comments and suggestions and consider adding them into the paper’s acknowledgements. Never be aggressive or rude and only write responses which you would be happy to say to a reviewer or editor face to face. Respond to all comments, no matter how trivial they may seem and show that you’re willing to make more changes if necessary. Don’t just ignore the bits that you don’t agree with. Show the editor that you have dealt with every comment by cross referencing the changes you made to the manuscript. To do this, either refer to the revised line numbers or, more preferably, cut and paste the sections that you have modified into your responses so that the editor doesn’t have to keep moving among different pages to check what has been changed.

Being polite and positive doesn’t mean that you have to be a push-over. If you receive a comment which is impractical, beyond the scope of your paper or just downright wrong, argue your point (with legitimate back up) but always retain a courteous tone throughout. If you have to deal with a whole slew of comments which are particularly off the wall or aggravating, ask someone to read your response before sending them to the editor – it’s always easier for someone else to pick up a passive aggressive tone which, despite your best efforts, may have crept into your writing.

If reviewers disagree on a particular point, either justify the changes you have made (don’t just ignore one reviewer’s comment) or your reasons for not making any changes. Don’t feel obliged to do everything that a reviewer suggests. Don’t ruin the flow of your text with awkward sentences which were clearly just inserted to please a particular reviewer. If you have good reasons (not just stubbornness or obstinacy) for sticking to your original ideas then make them clear. Remember that you can always get in touch with the editor if you get unrealistic or conflicting instructions or if you’re unclear about what you are expected to change.

So there’s our collective field guide to the trials and tribulations of academia. They’re by no means exhaustive but they’re definitely a good starting point. However, as academic publishing seems to require good fortune and timing as much as scientific rigour, research merit and an eye for a good story, there’s no magic formula for how to succeed, no matter how carefully you follow NERD club’s collective wisdom…

Happy publishing!

Author: Sive Finlay, sfinlay[at]tcd.ie, @SiveFinlay

Image Source: justinholman.com